![]() By Will Cracknell

By Will Cracknell

May 12 2020, 21.00

Follow @SW_Londoner

The accusation that professional English cricket is the preserve of the privately-educated is often thrown around like an errant delivery on its way back to the bowler’s mark.

The sport is frequently cited as being among Britain’s most exclusive professions, with a 2018 Sutton Trust survey finding that 43% of male and 35% of female cricketers who represented England went to private school.

🏏Congratulations to the #EnglandCricketTeam on their World Cup win🏏

— Labour Against Private Schools (@AbolishEton) July 15, 2019

But let’s not forget that 43% of men playing international cricket for England went to private school.

Our national sports teams should draw on the talents of all in our society – not just a privileged few.

This compares to just 5% of male and 2% of female footballers. Nationally, around 7% of the British population are educated at independent schools.

In 2017, Matthew Engel wrote in The Guardian there were “only three well-trodden routes into the English national team: through independent schools, existing cricketing families and, all too often, South Africa.”

But is it too simple to say the financial capability of a young cricketer’s family constitutes the decisive factor in whether they will make a career in the game?

In England’s most recent January Test match against South Africa in Johannesburg, seven (64%) of the playing XI received a private education.

But of those seven, four – Dom Sibley, Jos Buttler, Sam Curran and captain Joe Root – were awarded sports scholarships which allowed them to attend their respective independent institutions in Somerset, Yorkshire, Surrey and Berkshire.

The prevalence of such scholarships is rarely accounted for in conversations about the demographic make-up of professional cricketers, possibly because – according to Middlesex CCC’s Head of Youth Cricket Rory Coutts – of the relatively novel zealous approach adopted by some schools when recruiting promising players.

“The proactiveness with which schools go after potential scholars has changed,” Coutts said.

“I don’t remember scholarships being as widely available whereas now kids can get them. The number of players going to private schools now is probably different than it would have been years ago because it’s not necessarily down to whether you can afford it – whether the school want you there is also a factor.”

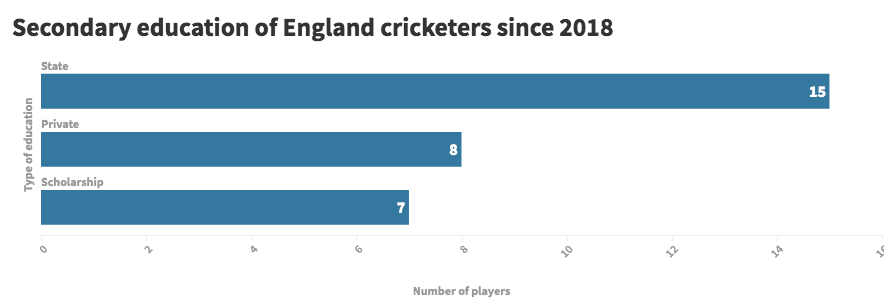

Indeed, of the 30 players to represent England’s Test side since 2018, 15 were privately educated but seven of these were done so on merit – that is, they were scouted and offered scholarships.

Why is this significant? While of course not every deserving young player is offered a full scholarship to one of Britain’s elite educational institutions to further their professional aspirations, it does suggest that talent, rather than disposable income, is a more fundamental ingredient in the recipe of cricketing success.

Take 2019 England Test debutant Dom Sibley, for example. Had the now-Surrey batsman not displayed precocious potential at a young age, presumably Whitgift School would not have felt inclined to offer him a place as a sports scholar.

The attraction for schools like Whitgift and Millfield to pitch themselves as sports institutions seems clear. Bring in the best players. Create competition in training.

The result? An environment similar in many ways to a mini county academy. Great for the school prospectus, but still a conduit – rather than a maker – for scholars who go on to enjoy professional success.

Moreover, there are multiple factors other than private school attendance which hold sway over the pace of a player’s development.

“It’s so individual,” Coutts explained. “Yes, going to private school kids get an opportunity to be coached usually by a good calibre of coach.

“However, the negative is they very much stay in their peer group. Whereas look at clubs like North Middlesex at the moment, where two state-educated players we just offered contracts – Luke Hollman and Joe Cracknell – grew up playing Saturday men’s club cricket.

“They’ve learned the game from men, competing in tough cricket week in week out. So despite some ‘benefits’ of attending a certain school, in my eyes it’s not an absolute bearing on whether someone will be successful or not.

“You could put on a red carpet with a golden platter in front of you, but if a player doesn’t have the desire, the work ethic, resilience, ability to learn from your mistakes then you will never make it.

“You can’t deny schools do give some very good opportunities but I don’t think that is the only deciding factor in whether or not a player will make it.”

There is no doubt English cricket has a long way to go before its international team even comes close to reflecting the population it represents.

Simultaneously, a more nuanced understanding of the determinants that make a successful cricketer is clearly required. Yes, regrettably, family background is and will continue to be a factor.

But it is not the decisive factor and it is that hope on which we must focus. Other influences – potential, talent, work ethic, increasing availability of scholarships, the role played by clubs and counties – can be altogether more powerful.

Feature image photo by Pete Willis on Unsplash