Upon entering Roehampton’s National Tennis Centre it strikes me I am deep in enemy territory.

As a Serb, I am bound to support Novak Djokovic and this partisan standing makes me feel uneasy in the surrounding environment.

It was just before my arrival that Andy Murray reunited with coach Ivan Lendl and announced dethroning Djokovic as their long-term strategy.

I confess my background to the receptionist to unload the burden. He laughs and comments with mock disapproval as I awkwardly shuffle on.

The centre has recently faced a programme of decentralisation following a controversial tenure under chief executive Roger Draper.

His successor, Michael Downey, decided that regionalisation of training centres was a better model and now the likes of Murray visit the centre just on specific occasions while mostly practising closer to home.

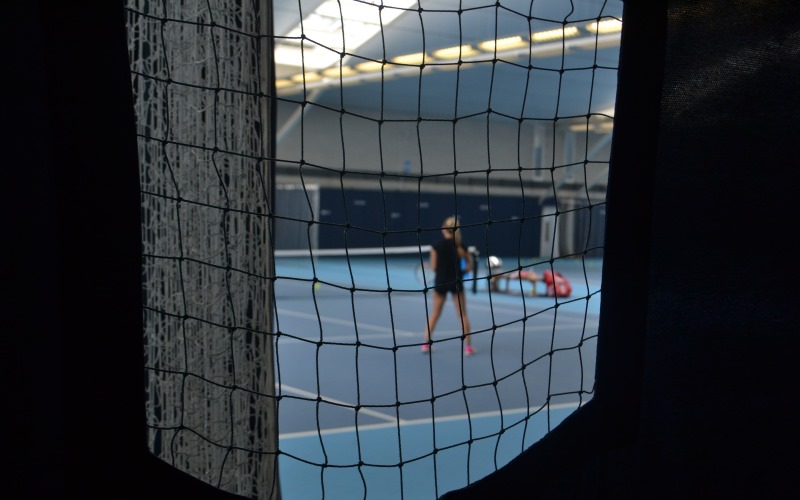

It seems a shame because, as the sports scientists I meet show me on my quick tour, this is a state-of-the-art facility.

Hawkeye cameras line the courts and somewhere hidden lies an altitude chamber.

It is sad to hear this does not result in a gloriously busy, regular congregation of Britain’s finest players but I do realise this will only help further spread the game.

ACE: The centre has 22 tennis courts

ACE: The centre has 22 tennis courts

For the behind-the-scenes professionals, the new status of the site as a drop-in centre only means they value meeting their players even more.

Adam Snook, performance analyst for the Tennis Foundation, said: “A lot of the year when the guys are away I’m working on their videos from tournaments and their matches.

“Building up a database. Looking at head to head stuff. But whenever the players are around — the coaches are around — that’s the important time to take your foot off the gas a little bit and not hide yourself away and get out and build on those relationships.”

Adam has been working with the Tennis Foundation, Britain’s leading tennis charity, since he graduated from Middlesex University with a Masters degree in Performance Analysis.

Having previously had a placement at football club West Bromwich Albion he landed into tennis after pouncing on a paid internship.

He praised his fortune in getting the job as the sector is inundated with talent — 15,000 people graduate from sports science degrees annually.

Mr Snook’s colleague, Gordon Howarth, is a performance analyst for the LTA who began his work shortly after a postgraduate degree in Sports Biomechanics at Loughborough.

He explained his choice of tennis as a consequence of the opportunities it provides to sports scientists.

He said: “It’s a very technical, skill-based sport.

“There is a lot of opportunity for performance analysis — technical analysis — where you can make a difference.

“There are all these subtle fine-tuning practices you can do which you can measure and monitor which makes our job quite interesting. “

The degree to which sports science has taken over the dressing rooms and training pitches all over the world has been well documented.

The strength of Rafael Nadal’s forehand has been labeled a scientific achievement in a myriad of ways.

From the way science helped break down his forehand and subsequently changed his grip to the technology used to improve the strings in his racket.

Football team Leicester City’s injury-free season, which aided their eventual Premier League success, is also understood to be partly due to manager Claudio Ranieri’s incorporation of sports science.

Competitiveness in the discipline has therefore grown.

HARD CORE: The centre has 22 bedrooms perfect for intense training sessions

HARD CORE: The centre has 22 bedrooms perfect for intense training sessions

In tennis, rival international associations will strive to advance their technology and stay ahead of others.

If one wheelchair tennis player begins using carbon fibre chairs successfully, other associations will start using it too.

Mr Howarth said: “I think it’s about a kind of a culture around each tennis environment, this moving into a sports science era.

“As soon as one governing body starts applying their sport science into player programs, it gets heard about or seen elsewhere and those companies or organisations then are thinking: ‘Actually they’re using this technology to improve their player. Actually we should consider getting that.’

“It’s like a never-ending arms race.”

This rivalry means Mr Snook and Mr Howarth have to remain fairly careful in what they say and discussion has to revolve around generalities and hypothetical situations.

Their area of sports science — performance analysis — revolves around receiving or capturing video footage of players in training and matches.

This footage will go through a process called tagging or coding where the analysts link data with video.

Once they code the match, they create a report based on the coding where they highlight which numbers are higher or lower in analysis than they should be.

For example, a player might have had 10 forehand errors in a match.

The report brings this up and the player’s coach, who acts as a funnel or gate-keeper of information from the support team, will receive a video alongside the report so they can view the forehands themselves.

It is then up to that coach to decide how to react to the received information.

For Mr Snook, who mostly works with wheelchair tennis players, the footage can contribute to decisions such as changing a wheelchair.

A chair change is quite pivotal in a player’s performance and therefore extensive filming is required.

They will record players performing perhaps fan-drill tests from different angles in different chairs in an attempt to compare the pushing and turning in their movement.

They have to take account a multitude of factors: the height of the chair, the size of and camber on the wheels and the position of the legs.

Mr Snook said: “It’s a big decision to make. It’s not like changing your trainers.

“It really can affect your game.”

Mr Howarth trains elite Great Britain tennis players including the Davis Cup Team.

There is immense importance in retaining a service game in a match as if it is lost the player will be more prone to losing the set or the match.

Mr Howarth will analyse what makes an individual’s serve successful as well as the reaction to the third ball, which is the ball hit after a serve is returned.

Even physios will use technology to best inform their decisions. They now focus on injury prevention by monitoring training loads of players and benchmarking them.

If a player is pushing themselves too hard one week a physio can advise against it, based on prior history.

Suggestions can also be established on previous injuries.

A physio can point out what conditions brought about the injury before and can warn the player if such conditions rise again.

Coaches then act as a balance for all this information as change can have a large impact on a player.

Stuart Wilkinson, a coach with the Tennis Foundation explained: “Everything has a knock-on.

“When you change the serve then the movement has to change and the first push direction has to change.

“So that’s where you have to look at the value of the change and the time you’ve got to do it and what long term aim there is.”

Karin Ross, head of coaching and talent with the Tennis Foundation, held a similar opinion.

She believes only technical changes to prevent injuries can justify an immediate change of focus in large training blocks.

Smaller technical changes, such as the ball toss, can even be made during tournaments.

Although she warned of over-analysis, she praised the sports scientists.

She said: “Tennis has moved on a huge amount.

“There’s different equipment. For us with the chairs, it’s so complex because it’s not just about being on your feet and using your legs it’s the type of chair that suits your disability.

“There’s a lot of things we have to consider that able-bodied coaches don’t have to consider.

“The range of the disability, what factors we can take into consideration, how we can help their body to do things that perhaps the disability restricts them from doing.

“So that sort of research and everything is invaluable to us.”

Ms Ross praised a holistic approach to coaching where information from all support staff is considered.

Mr Snook and Mr Howarth see Britain’s victory at the Davis Cup last year as evidence of such an approach.

There the players, physios, strength and conditioning coaches, nutritionists, performance analysts, doctors, racket stringers and coaches combined well to not only win the cup but also to win BBC Sport Personality’s Team of the Year of which Mr Howarth was a part of.

Key decisions, such as the aforementioned wheelchair change, will require similar teamwork.

The increase in the use of sport scientists has been a hot topic of late, with football pundit Rio Ferdinand criticising their influence in sport.

Mr Howarth admitted there is a line that should not be crossed and argued that their suggestions are based on scientific evidence — they provide facts not opinions.

Mr Snook said that they are, after all, only there to support through suggestions and not to make decisions. That is the coach and player’s position.

He said: “It’s their body. Their performances. Their match.”

The future of sports science, in their opinion, will be less about collecting data and more about pure performance analysis.

The pair believe sport scientists will soon need different skill sets and more of a statistical mind.

Having made it out alive, I can only hope now that somewhere Djokovic is reading this.