Where to find clues to the complexities of those who live in palaces is a constant question for journalists and biographers, and the schooldays of Queen Elizabeth II has intrigued many over the years.

Predictably, the growing pains of Queen Elizabeth II’s education will be kept as anecdotes among her family, and perhaps those of her tutors.

But in 1949, when Queen Elizabeth II was 23, something shocking happened. Woman’s Own Magazine in the UK and Ladies Journal in the US published a long memoir by Marion Crawford – Princess Elizabeth and Margaret’s trusted tutor and friend.

The fragile nature of being an employee in the heart of a family was reflected in The Queen Mother’s response: “The governess has gone off her head.”

Crawford’s subsequent book, The Little Princesses, could be described as a series of tableaux illustrating a lifestyle, although we can paint in the gaps of what Elizabeth’s inner world might have been.

Crawford writes: “Life in a palace rather resembles camping in a museum. These historic places are so old, so tied up with tradition, that they are mostly dropping to bits.”

The most interesting section of the memoir is Crawford’s description of a surreal transition – that of Elizabeth and Margaret moving from an upper-class townhouse in Piccadilly to Buckingham Palace.

Aside from the governess’ gossipy commentary around the subject of the abdication, what splashes from the page are the Princesses swimming lessons at The Bath Club.

Crawford writes: “The little girls were always anxious to do what other children did. They longed to swim and I suggested this. The Duke and Duchess were very good about allowing these innovations.”

Amy Daley, a celebrity coach, was charged with teaching the Princesses swimming and life-saving – a hobby deemed inappropriate by senior members of their family.

What emerges is a picture of Princess Elizabeth as a pragmatic monarch-to-be and one of Margaret as a loveable jester. As Margaret tentatively hovers by the pool, Elizabeth calls: ‘Don’t be a limpet Margaret!’.

Crawford writes that in the girls’ first exercises, Miss Daley: “Laid them over a wooden bench and taught them the motion of swimming by asking them to make the marks of letters…Margaret turned to Lilibet and said ‘You look like an aeroplane about to conk out.”

The watery vignettes depicting the princesses’ penultimate sessions are genuinely affecting as they touch on the notion of achievement where there is privilege.

Crawford’s pointed comment that the lessons “Were a great diversion at that time and took our minds off other matters” underlines the challenge of modern royals – to engage in a common reality, while living a high-stakes version of it.

The question of how to bring formal education into a diplomatic household was grappled with by King George.

Crawford introduces the problem of a ‘schoolroom’: “The king took me up to see one – it was one of the darkest and most gloomy rooms in the palace…the whole atmosphere was regal but oddly dead.”

With a brief ‘This won’t do,’ Elizabeth’s father arranged for a space which by contemporary standards would be appropriate for learning.

This is perhaps the last significant reference to formal education in the Little Princesses, as the politics and ritual of royal life takes over.

Little is publicly known about the other tutors who intermittently shaped Elizabeth’s young mind, but there are records of tutorials taking place.

In a 1943 article for The Atlantic, Wilson Harris addresses the educational credentials of Britain’s new female heir, while comparing her to a former Queen in training – Victoria.

He writes: “Princess Victoria was a skilful horsewoman, a good musician, and a singularly keen dancer. But there is no reason to suppose that she was a swimmer, and much reason to suppose that she was not.”

It’s clear from Harris’ article that Princess Elizabeth was not only being educated as an aristocratic woman but also as a modern leader in training.

Canon Crawley’s bible studies lessons are more of a mystery – on enquiring about records he may have kept, St George’s Chapel, Windsor could not find any.

Marten, on the other hand, has been legendary among Etonians for his eccentricities, including keeping a live raven in his study.

In her biography, Elizabeth, The Queen, Sally Bedell Smith writes: “Elizabeth was thirteen and bashful with the tutor, often looking at her governess as she learned her lessons. Marten, an eccentric scholar, was also uncomfortable, probably at the pressure at serving as tutor to the heir to the throne, and sometimes called her ‘gentlemen.”

As Elizabeth became a young woman who hid her feelings for Prince Phillip of Greece from her governess, formal education took a back seat to a new kind – recognising the administration, rituals and faces of power.

One thing is plain – that in her exposure to the talent that serves power, Queen Elizabeth II contained a unique knowledge of human nature – the kind that wouldn’t be handy to satirists or tabloid newspapers.

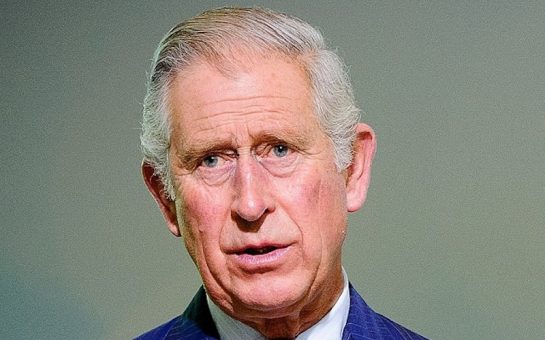

Featured image credit: Creative Commons (CC BY 2.0)