There has been an epidemic of eating disorders in London since the pandemic, and NHS waiting time targets for under-18’s have not been met since.

Referrals for under-18’s have risen by more than 150% and referrals for adults have risen by more than half since 2016 across London, a City Hall freedom of information request shows.

The data, combined with NHS figures, also shows that since the pandemic most trusts have been failing to meet stipulated government waiting time targets for under-18’s and adults can wait more than three years for help.

Dr Bryony Bamford, Clinical Director at The London Centre for Eating Disorders and Body Image said: “Waiting times for NHS treatment for both young people and adults with eating disorders have been unacceptably long for years now.

“Services are truly at breaking point and only when this is recognised and acknowledged at senior levels will we have a chance of moving towards being able to meet the needs of this highly vulnerable population.”

Baroness Parminter, a member of the Lords, whose daughter has anorexia said: “If you were to do a correlation between the prevalence of eating disorders and treatment levels, it’s just laughable.

“Unless there is more funding, the targets that aren’t being met are never going to be met.”

Waiting Times

Since the pandemic eating disorder cases, which have been rising for 50 years, have skyrocketed with adult cases as well as child and adolescent cases more than tripling.

After an inquiry into the death of April Hart, 19, from anorexia determined that NHS failures amounted to neglect, the government set target waiting time targets for under-18’s.

The target stipulated 95% of urgent cases should be seen within a week and 95% of routine cases within a month by 2020 and allocated an extra 150m funding.

Despite initial improvement with targets almost being met in 2019/20, since the pandemic London trusts have struggled to meet the targets.

In 2020/21 they dipped below 2016/17 levels hitting 64% for urgent cases and 65% for routine.

It should be noted that due to a cyber attack last year, the data may be inaccurate marring evidence of recent improvement.

Eating disorders are severe mental illnesses, which can have dire physical consequences which can further reduce cognitive function making them harder to treat.

Dr Brian Sereen said: “Whilst people wait and physically deteriorate, your brain is starved and if you are offering them therapy, they are not going to engage as they would engage if they were properly nourished.”

City Hall’s investigation found for many, the extent of support provided on waiting lists is pamphlets.

There is also a postcode lottery amonst waiting times depending on NHS trusts across London, with some struggling with elongating waiting times more than others.

NHS guidelines state that extremely high or low weight should be taken into account when deciding treatment but should not be the sole factor and that other physical and mental health indicators should be taken into account.

However, due to the scarcity of beds the NHS has fallen into crisis management where they have to prioritise keeping those with the lowest weights to keep them alive, often discharging them before they hit a healthy weight making relapse highly likely.

Daisy, a therapist in recovery from anorexia spoke of her NHS experience.

She said: “I remember I was at a very low weight, and they said if you get below this certain weight we have a bed.”

She described the current pattern of refeeding patients until they hit a BMI of 15, a minimum healthy BMI is 18, discharging them, at which point many lose weight again as cognition is still low and get readmitted creating an endless cycle of readmission.

Kyla, who was on a waiting list for six months aged 17 in 2021 after being diagnosed with anorexia and bulimia, said: “Waiting for an assessment and treatment made my eating disorder worse, I felt I needed to be good enough at it to get help or be taken seriously.

“The clear message was that I had to get dangerously ill before I would actually get any access to support.”

Paula, who was diagnosed with atypical anorexia in 2020 aged 15, said: “Being told there was an 18-month wait, and that even then the treatment was unlikely to be sufficient was soul destroying.

“You’ve opened the wounds but don’t have a plan.”

Three families we spoke to had to remortgage their house to pay for private treatment.

A month of inpatient care in the UK is roughly £30,000.

Adult waiting times

There is no target waiting time for adults, however the FOI data demonstrates a postcode lottery in London trusts for waiting time for adults which can be over three years.

Adult waiting times have on average improved since 2016/17 with 61% of adults referring to starting treatment within four weeks and 33% in a week in 2022/23 compared to 42% in a month, and only 13% in a week in 2016/17.

This has been achieved despite the increase in referrals.

However, four practitioners highlighted the disparity in services for adolescents and adults, with the latter enjoying significantly lower funding.

Dr Sereen said: “There’s a two-tier system when a 17-year-old can wait a week for an urgent assessment and then an 18-year-old has six months to a year of waiting time.”

There is enormous variation amongst London trusts, a postcode lottery with South London patients sometimes waiting over three years.

The number of adults waiting 12 weeks or more has not decreased in recent years as it has for young people with 18% of adults waiting for more than three months last year compared to 4% of children and young people across both urgent and routine cases.

Baroness Parminter said: “Without a waiting time standard for adults there will not be the drive to improve access to services and more lives in London will be destroyed by these cruel diseases, when we know early treatment offers the best chance of recovery.”

Mental health campaigner and researcher James Downs, 34 said: “I’ve had a severe eating disorder for over 20 years and been on many waiting lists.

“In my experience, being in a waiting list is not harm-free.

“I’ve even been admitted to hospital with life threatening health problems whilst being on a waiting list or even when I have been refused access to specialist treatment because my weight hasn’t been low enough.”

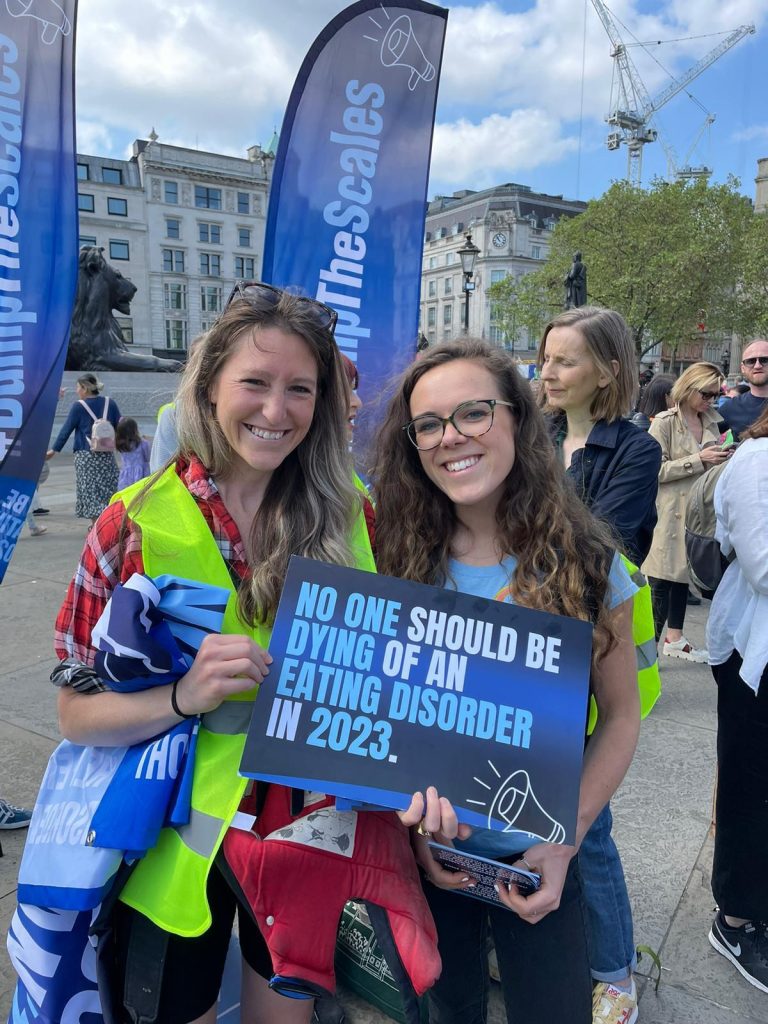

Hope Virgo, a national campaigner with lived experience and founder of the dump the scales campaign said: “I welcomed waiting time targets, but whilst patients may get seen within two weeks for the initial appointment they are then put on waiting lists for months, sometimes over a year with no support.

“The way eating disorders are being tackled is a national disgrace.

“Even though it is widely known that they are becoming increasingly common with high mortality risks this is a national emergency that is not being addressed.”

This is just the tip of the iceberg with concerns being raised about care being withdrawn from chronic patients, the quality of treatment once achieved, and the difficulty in obtaining a referral from GP s who only have two hours mandatory training within their degree.