Several universities and charities have partnered to undertake a two year study to enhance the UK’s response to domestic abuse and child protection.

The study, which began in February brings together Kingston University, the University of Sheffield, the University of Huddersfield, domestic violence charity, SafeLives, and education administration programme, Research in Practice.

The partnership, funded by Nuffield Foundation, arrives at a time of greater need to improve and monitor protection services following the pandemic.

Professor of Social Work at Kingston University, Rick Hood, said: “The aim of the study is to address what we see as significant gaps in knowledge that exists about the nature and characteristics of domestic abuse and violence in the field of child protection.

“What we hope is that our research will provide not only new knowledge, new information, but also new tools.”

Professor Hood commented that specific details of child welfare services during the pandemic were largely unknown, with a potential reason being that services may have been less accessible, and thus less documented.

Professor Brid Featherstone, Professor in Social Work, Department of Behavioural and Social Sciences at the University of Huddersfield, co-led research that led to the study over the course of the pandemic.

She said: “The pandemic has intensified already existing inequalities in our society.

“It is really, really important that we make people aware of the multiple implications of increasing poverty rates throughout our society.”

The research explored ways in which services were already developing new types of practices and understanding, and working with families.

Rather than examining the number of reported cases which fluctuated during lockdown, one can more accurately identify whether the past few years saw an increase in the need for child protection services, through the recorded number of assessments by social services, and their follow up through Child Protection Plans (CPP).

CPPs evaluate when a specific child is at risk of significant harm that affects their health, welfare and development.

Plans are created following a conference with all those involved, including the parents, on how the child can be kept safe.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) identifies a massive increase between 2014 and 2015, followed by a slight dip for 2021, when the UK would have been in various lockdowns.

The same can be found in the number of assessments by children’s social services which also had a gradual increase between 2014 and 2021, followed by a small decline last year.

Source: Office for National Statistics (ONS)

Source: Office for National Statistics (ONS)

The Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) estimated that in 2019, one in five adults aged between 18 and 74 years, experienced at least one form of child abuse.

However, this number could be higher as the many cases of child abuse remain hidden.

Charity NSPCC confirmed that only around one in seven adults who called the National Association for People Abused in Childhood’s (NAPAC’s) helpline in 2022, had shared their history of being abused.

Whilst the NSPCC’s website states several reasons for abuse not being noticed, one recurrent theme is the fear that their abuser would find out or that the abuse would get worse.

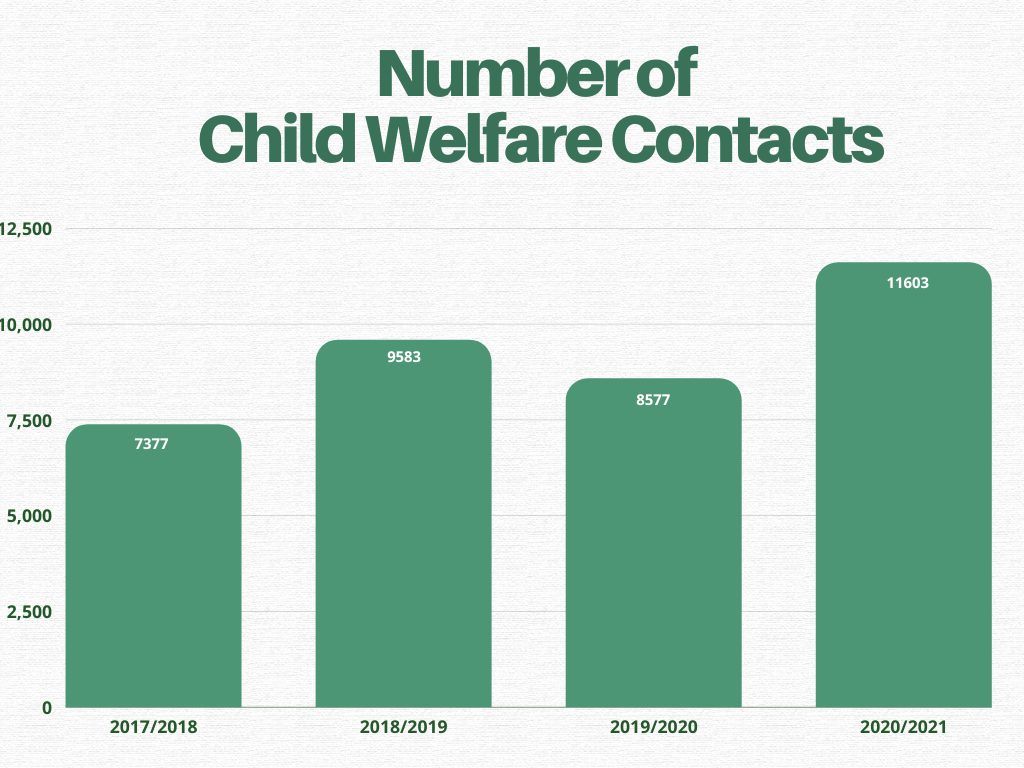

Whilst assessments and records may have declined in 2021, the NSPCC helpline confirmed that during the pandemic there was an increased number of ‘child welfare contacts’.

These refer to people contacting the helpline when they are concerned about the welfare of a child, and can be attributed to the greater stress and isolation of lockdown that would have contributed to unsafe environments.

Studies undertaken by the University of Huddersfield also showed a correlation between child abuse and domestic abuse, something that the partnership will further investigate.

The university found that more than 25% of children in the UK were estimated to live with an adult who has experienced domestic abuse and violence.

This was further discovered by refuge workers when children who entered care, often had sleep or concentration problems at school.

Many children who witness or face domestic abuse often experience short and long term cognitive, behavioural and emotional effects.

The Adoption and Children Act 2002 amended the definition of ‘significant harm’, to include the experiences of a child living in a domestic abuse environment.

Domestic abuse is defined by the NSPCC, as any type of controlling, coercive, threatening behaviour, violence or abuse between people who are, or who have been in a relationship, regardless of gender or sexuality.

The term is often used to describe the abuse between adults, but now covers the exposure of children to hostile environments, and is considered a safeguarding issue.

One such reason for unsafe environments can be linked to the economic situation of a family.

The new research will explore this issue, building on the previous work by Kingston University on welfare inequalities.

Results from the ONS showed that adults, who lived in urban areas, were more likely to have experienced domestic abuse (6.0%) than those who lived in rural areas (4.2%) in 2019.

Source: Office for National Statistics (ONS)

The result of London having a significantly increased number of domestic abuse incidents in England and Wales is unsurprising, as the busiest region in the UK.

Given the recent rise in cost of living, there are concerns that domestic abuse and child abuse will continue to increase.

The Domestic Abuse Act was only passed in 2021 to raise awareness and understanding about the devastating impact of domestic abuse on victims and their families.

One particular clause within the act aimed to clarify the circumstances in which a court can make a barring order under section 91(14) of the Children Act 1989, to prevent family proceedings that can further traumatise victims.

Although the study is in its early stages, it is hoped that the findings will shine a light on some of the most important issues and bring them up for discussion.

Professor Featherstone said: “We’re too often relying on [the] law and the police and the courts, but actually, we need to really tackle culture.

“A public health approach would mean really tackling things at different levels and that would include prevention.

“I want us to make more services available to those who are impacted, including those who are harming, to change behaviours, that’s really important.”

The results of the study will be available in 2024.