Official figures estimate that around 25% of adults in prison have either diagnosed or undiagnosed Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).

However, many of those that specialise with the issue of neurodivergence in the Prison System believe that, if the curtain was pulled back and it was looked at in closer detail, that figure would be considerably higher.

According to Revolving Doors, an organisation that champions long-term solutions for justice reform, it is estimated that around half of people entering prison have some form of neurodivergent condition. This could be dyslexia, autism, acquired brain injury, and of course, ADHD.

This over-representation of neurodivergence behind bars must be acknowledged and analysed to fully comprehend the current state of the Prison System in the UK.

Why is it that more neurodivergent people are ending up in prison? Are their needs being met whilst incarcerated? Are these people even aware of their condition? And could more awareness of this issue actually alleviate the overcrowding crisis in prisons and break the cycle of reoffending?

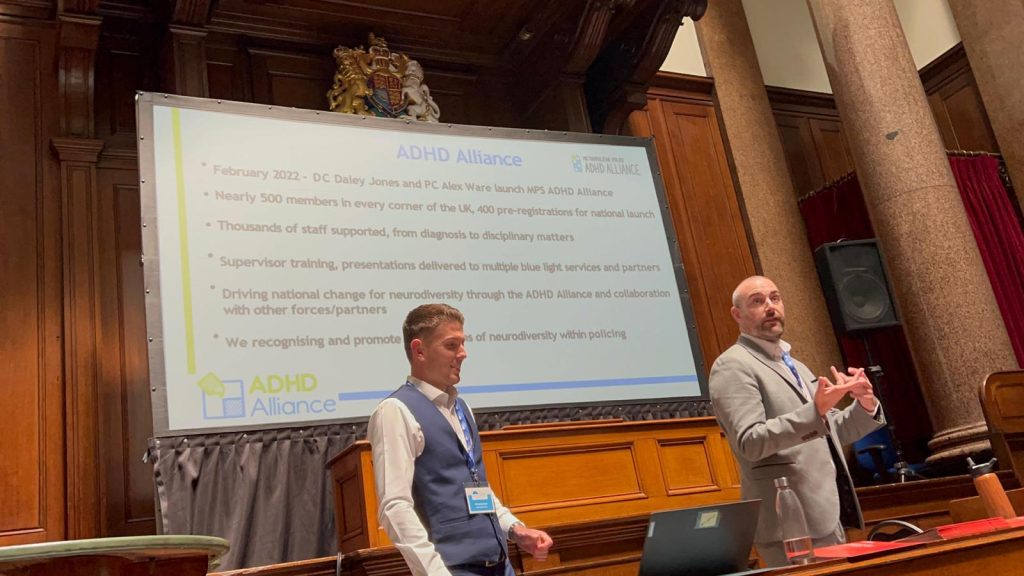

Well someone who is asking these questions on a daily basis is Met Police Detective and campaigner Daley Jones.

Daley was first diagnosed with ADHD when he was 36. From that moment, everything began to make more sense in his life and he could finally start to understand why he acted and behaved in certain ways.

Since then, Daley started raising awareness about ADHD in the Prison System and became a trustee for ADHD Liberty, an organisation which aims ‘to stop people with ADHD ending up in prison, whilst also helping those who are already in prison as victims of a criminal justice system that does not help or understand them.’

Daley explained that there can be traits connected with ADHD, that if not properly managed can lead to involvement in criminal activity and offending behaviour.

For example, Daley described how people with ADHD can struggle with emotional dysregulation. This means that people with ADHD can be quick to anger and quick to take offence due to a trait called ‘rejection sensitive dysphoria;.

People with ADHD can also have a ‘strong sense of justice and can be incredibly impulsive thrill seeking people’.

Equally, people with ADHD also have a dopamine dysregulation therefore they could be pulled towards various forms of addiction to get that dopamine hit, and fulfil the urge to thrill-seek.

Daley added: “I think there’s a lot of people that are getting unwittingly punished for conditions that they don’t realise they have.

“I would strongly suggest there are a large amount of people out there who are addicted to alcohol … and are self-medicating without even realising.

“I, Daley Jones, am a white middle-class male. I am probably in the most privileged 2% of people on planet earth. I think that’s the reality.

“I have had a life of opportunities and stability that a large amount of people in this country and certainly in this world will never have.

“And I know how much I struggled with my undiagnosed ADHD and my undiagnosed dyspraxia, I can only imagine what that might be like for somebody who is from a far less privileged, far less stable background where let’s say hypothetically there is domestic violence or drug use or criminality in the household.”

Daley emphasised that of course not every person who has ADHD or another neurodivergent condition will become involved in criminality but rather that these traits, if not properly managed, could potentially lead to such involvement.

He continued: “I have met very few people in my career who I think were born bad.

“Don’t get me wrong you get exceptions, I am not saying there isn’t a time and a place for prisons but I think a lot of people who end up in prison are a victim of circumstance, a victim of socio-economic lottery.”

Daley also partially attributed the overcrowding crisis in UK prisons to this lack of awareness surrounding ADHD and neurodivergence in prisons, and how offering people the appropriate support could break the cycle of reoffending.

An online article written by Zahra Wynne for Revolving Doors entitled ‘Can ‘neuroinclusivity’ cut crime?’, supports this viewpoint.

In it, Wynne, the Policy Manager at Revolving Doors, writes: “It’s essential to remember that people do not get caught up in the criminal justice system only because they are neurodivergent.

“Rather, it is often because systems and services have failed to recognise neurodiversity and therefore tailor their approaches.

“This effectively denies people who are neurodivergent essential support to thrive, from when they are in school up until when they enter the criminal justice system.”

In July of 2021 a report was released by the Criminal Justice Joint Inspection entitled ‘Neurodiversity in the Criminal Justice System: A review of evidence’. It found that often neurodivergent people are more vulnerable and susceptible to getting involved in criminality and how, often, the system is not fair towards these individuals.

It also found that there was a lack of training for police officers and people who work in prisons around neurodiversity and those that need support regarding their neurodivergent condition, stating that: “There is certainly no guarantee that a neurodivergent person coming into contact with the CJS (Criminal Justice System) will have their needs identified – let alone met – at any stage of the process.”

After this report a number of organisations, such as ADHD Liberty, launched initiatives based on the key recommendations of this report; to introduce screening in all areas of the criminal justice system and analyse that data.

In May of this year, ADHD Liberty launched a voluntary ADHD screening pilot with City of London Police which offered anyone coming into the police station a voluntary ADHD test.

The aim of the pilot is to ‘help identify those with ADHD entering the criminal justice system at an early stage, allowing for a quick referral for diagnosis and get them the support they need.’

It also aims to provide a more enhanced understanding of the type of crimes committed by those with ADHD and aid the prevention of further reoffending.

According to Daley Jones, who is also a trustee for ADHD Liberty, so far 63% of those who have taken part in the screening have come back as probable or highly likely to have ADHD, which highlights the inaccuracy of the earlier 25% figure.

Equally Neurodiversikey®, an organisation which aims to change the way the civil and criminal justice system views neurodivergence, in association with the ADHD Alliance, have created a guide called ‘ADHD in Custody A Guide to Police Custody for ADHDers’.

The organisation has encouraged police custody blocks to make this guide readily available for anyone entering their custody suites.

The guide is aimed at detainees in police custody, providing basic information about ADHD and legal rights, including Appropriate Adults. It aims to empower ADHDers through the custody process and ensure fairness and effectiveness.

These initiatives highlight progression in attitudes towards neurodivergence in the Criminal Justice System and, with any hope, the move towards further neuroinclusivity will result in increased support for those with neurodivergent conditions in prisons and, ultimately, reduced reoffending.

Daley Jones indicated just how powerful these initiatives really could be going forward. He said: “There are people who I have met who have spent their life as career criminals who have then been diagnosed and/or medicated who have been able to get on the straight and narrow.

“I think that’s incredibly powerful, I don’t know why we wouldn’t want that as a society.

“What do we, as a society, want prisons to be? Do we want prisons to be somewhere where we can lock up and forget about our problems?

“Or do we want places where people can go and be given every opportunity to turn their life around and change.

“I want, as a member of the public, people to come out of prison as better and more well-adjusted people than before they went in and that is not the case at the moment.”

Featured Image: Marco Chilese on Unsplash