Representation of black professors at London universities is proportionally worse than the rest of the country, according to data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA).

At 0.89%, a higher percentage of the capital’s professors are black compared to just 0.72% of professors across the country.

However, when you consider that as a percentage, London’s black population is more than three times the national average, black professors are hugely underrepresented in the city.

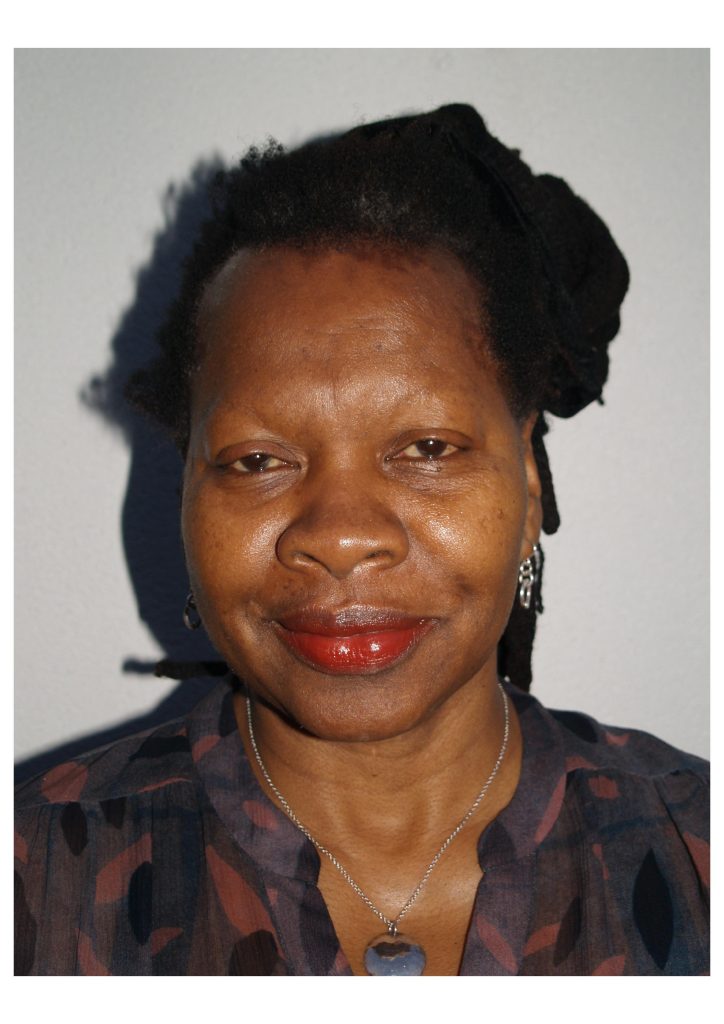

Professor Louise Owusu-Kwarteng, a Professor of Applied Sociology at the University of Greenwich put this down to two things.

She explained: “Even though London is more diverse, it is still very much a microcosm of wider society.

“It’s still very much a structural issue with structural racism, structural discrimination, and even though it’s better here, it still affects people’s opportunities.”

Structural racism means that organisational practices perpetuate discrimination based on race, leading to failures in supporting people from racially minoritised backgrounds.

The impact of racism in education, at both a young age and at university level, cannot be understated as it creates narratives from an early age that require significant effort to overcome.

In higher education, this can be evidenced by the lack of representation of black professors in London and around the country.

This disparity means that black students rarely see themselves represented in their professors and can reinforce the idea that careers in academia are not a viable possibility.

Professor Owusu-Kwarteng believes this underrepresentation discourages black students from pursuing academia, preferring instead to pursue other paths.

“It depends on the university, but if students don’t see themselves represented it might be a case of ‘I’m just gonna get through, get to my next stage, get my graduate job’ and they might not think they can go into academia,” she said.

“I’m not saying it makes them more likely when they have seen representation, but it will give people the option to say, ‘This person is relatable, they may understand what it is that I’ve been through’.”

With so few black students going on to become professors, this emphasises the need to increase representation in academia.

The underrepresentation of black professors at UK universities is not a new story, but significantly there has been very little progress in addressing this.

In 2014, data from HESA showed a mere 0.38% of professors in the country and just 0.74% of professors in London identified as black.

The national average has advanced by just 0.34%, but concerningly London’s representation of black professors has grown even less, by only 0.15%.

This means that in almost a decade, London has made considerably slower progress than the already slow progress across the country.

There are efforts being made to change the profile of British Academia with projects such as Generation Delta, which aims to nurture the next generation of black Asian and minority ethnic female professors in England.

Professor Claudia Bernard, a Professor of Social Work at Goldsmiths, University of London and mentor for the project, said that investment is integral to making progress.

She said: “Unless institutions invest, and unless funders invest in growing those areas, that isn’t going to happen overnight.

“A lot of black female professors like myself didn’t have that.

“We didn’t have that grounding and support at the start of our careers, we just stumbled around and managed to navigate the barriers, but Generation Delta is starting with young academics in their early career.”

As a mentor of the programme, Professor Bernard is helping to address this underrepresentation by supporting racially minoritised early career academics.

In doing so, she can better offer advice to mentees on their approaches to research or on the topics they are researching.

She said: “A lot of black PhD students from other institutions contact me to say they’re struggling because supervisors don’t understand they want to explore the topic from an intersectional perspective, a black feminist perspective, or a critical race perspective.

“Those things have a real impact on students and can demotivate them or make them want to give up.”

University is an opportunity to further your own knowledge, but at the same time the research undertaken at these institutions plays a crucial role in informing how we view the world.

With so few black professors, much of the research produced is limited to the experiences of white professors, meaning the narratives are largely framed from that perspective.

By having more black academics, the work universities do takes on a more diverse and representative character because it encourages research into areas such as critical race theory, intersectionality and decolonisation.

Given the statistics from HESA, the country is severely lacking in this regard, but London in particular is struggling to better its representation of black professors.

Projects like Generation Delta, Social Transformation and Advocacy through Research, and In2Research, are evidence that efforts are being made to address this, however there is still clearly much to do to speed up the rate of progress.

Feature image credit: Professor Louise Owusu-Kwarteng