The birth rate in London has fallen to its lowest level on record, after declining by nearly a third since 2010, new data shows.

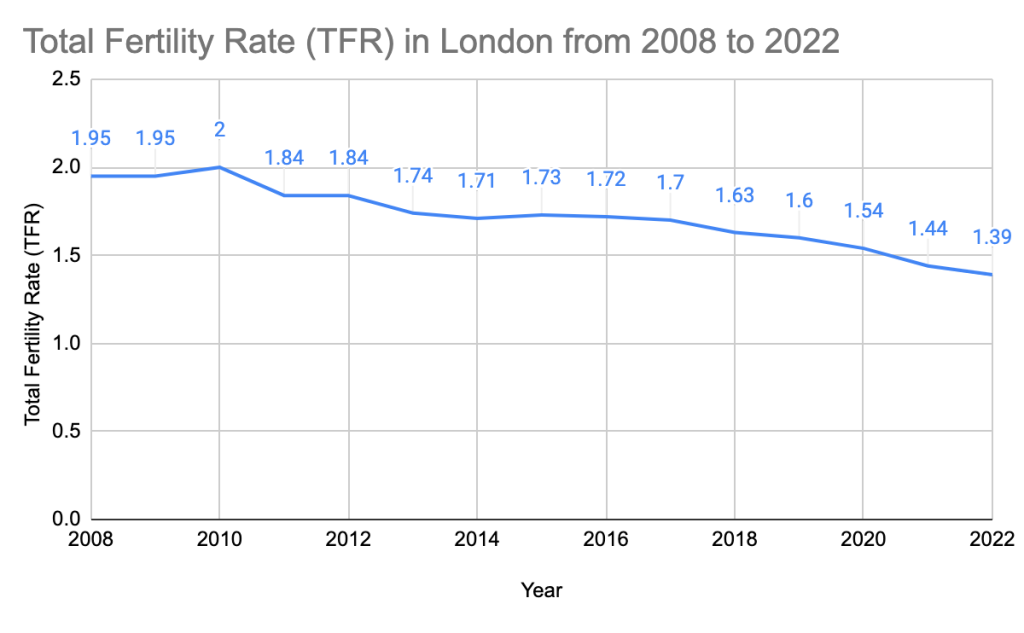

The Office of National Statistics, which has collected data since 2008, revealed that the capital’s total fertility rate (TFR) decreased to 1.39 children per woman in 2022 from 1.44 in 2021, 1.54 in 2020 and 2.00 in 2010.

This comes as fertility in England and Wales also hit an historic all time low, with 605,479 live births recorded last year.

The rate in England and Wales was 1.49, which is below the 2.2 generally considered to be necessary to maintain population levels in developed countries.

The TFR is the average number of live children that a group of women would bear if they experienced the age-specific fertility rates of the calendar year throughout their childbearing lifespan.

In total, there were 106,696 living babies born in London in 2022, down 3.8% from a year earlier and 17% of the 134,186 live births recorded in 2012.

But the reasons behind London’s continued baby decline are varied and nuanced.

UCL student Sophie Gregory, 28, said: “Saving up is extremely difficult. I think women here don’t consider children until they edge closer to 30.

“A lot of my friends still haven’t met their life partners or finished their degrees so kids are becoming less of a priority.”

Many experts have said that the decrease is part of a broader post-industrial trend and is evident across the world, while others have linked it to London’s soaring childcare costs and the cost of living crisis.

If this downward trend is to shift and lead to the predicted post-Covid baby boom, the natural next step is to identify the factors driving the falling rate.

Aveek Bhattacharya, chief economist at the Social Market Foundation, Britain’s leading cross-party think-tank, believes that several overlapping factors are all in-play at once.

He said: “London is at the bleeding edge and is particularly extreme because costs have gone up a lot and are more of an issue here.

“Parts of central London can feel like quite a weird place because you look around and think where are all the kids?

“In recent years the low birth rate has become a worrying trend. It’s worse for the people who would like to have children but aren’t because of economic insecurity or the prohibitive cost of childcare.”

London lowest regionally

Moreover, the capital suffered the lowest fertility rate nationally, when compared to all other English regions in 2022, the data shows.

The West Midlands had the highest value of 1.62 children per woman, with the East region’s 1.58 rate placing second.

The South West, North West and Yorkshire joined in being three of the five regions above the national average of 1.49 children per mother.

Bhattacharya explained: “There’s an impact on broader society and this plays out in lots of different ways. The decline has implications on the demographic pyramid.

“It means the dependency ratio (the sum of the youth and old-age ratios) goes in the wrong direction and so we have more elderly people who are out of the workforce and fewer working age people who have to carry the load.

“There will be fewer people paying tax and being economically productive, and more people requiring pensions and social care.

“And that is an economic challenge to manage. It brings fiscal challenges for the states trying to manage public services.”

Interestingly, though, London itself has variable disparities within, particularly those between the inner and outer boroughs.

In 2022, the outer authorities recorded a higher TFR for the fifth consecutive year, with a figure of 1.61 children per woman, which is 26% higher than inner London’s 1.19 rate.

Barking and Dagenham had the highest TFR of 1.98 children per woman, with Redbridge coming in second and Harrow third with a rate of 1.77.

The City of London had the lowest rate of 0.63, which amounted to just 65 live births in 2022.

In London, two-thirds of live births in 2022 involved parents where either one or both were born outside of the UK, the highest percentage of such births of all the English regions and Wales.

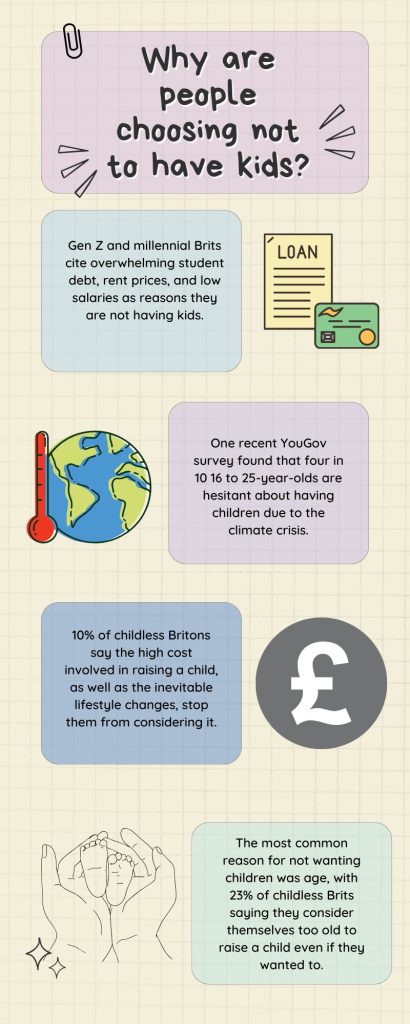

A report from HSBC on the UK’s demographic dilemma outlined three primary causes of the declining birth rate: later first-time parents, affordability, and social change.

Affordability includes periods of high inflation, negative real wage growth and economic uncertainty, which likely weigh on the willingness and ability of many couples to be able to start a family.

But there are also more elusive reasons why people are choosing not to become parents.

Claire James, 37, an account manager from South London, has a four-year-old son but she and her partner have decided not to have any more children.

She said: “After rent and childcare costs there’s nothing really left every month. We’d love to go on holidays and have more space to manoeuvre in, so bringing another child into our lives would feel way too stressful.”

Soaring childcare costs

The average cost of childcare in the UK for children under two years old is £138 per week (part-time) or £263 per week (full-time) according to the National Childbirth Trust (NCT).

These costs are more expensive in London, with some families having to spend £45 more a week on staff for their children than the British average.

James added: “As both me and my husband work full-time, it’s quite deflating to see half of our outgoings go to the nursery and childminders.

“My mum does help when she can, but she’s getting older now, so balancing everything is really difficult.”

What can the government do?

For Bhattacharya, the question of when and how the government should intervene is a complex one.

Politicians in the UK have tended to be wary of encouraging people to have more children, for fear of being seen to interfere in voters’ private lives.

He said: “British politicians are pretty squeamish still for the most part about even talking about this and having government policy support a higher birth rate.

“I don’t think we realise the extent to which Britain is a bit of an outlier. For example, Emmanuel Macron in France has made comments relatively recently about demographic rearmament.

“There are ways in which politicians could talk about this a bit more carefully and politicians struggle to get their arms around medium term problems.

“At one point Labour leader Keir Starmer had a slogan saying: ‘Britain should be the best place in the world to grow up’, which lends itself quite naturally to that angle of well, why do people feel they can’t have children and isn’t that a failure of ours as a society?

“But when it comes to crunchy policy, I think the difficult thing is to really move the dial. It’s going to be costly. Cheap talk is not going to cut it.

“And in fact more kids actually makes the dependency ratio worse before it makes it better, because those kids are not going to be producers until they’re 18 and frankly, they’re probably not going to be producers until they’re into their mid 20s.

“So they’re a drain on public resources until then. If we increase the number of kids born today, we won’t really get much of a payback until the late 2040s or early 2050s.

“So you have to be quite farsighted to get out ahead of this. And that makes that politically challenging, but equally I think everyone can look at the numbers and say this looks bad.”

Featured image credit: Ben Grey via Flickr under CC BY-SA 2.0 licence