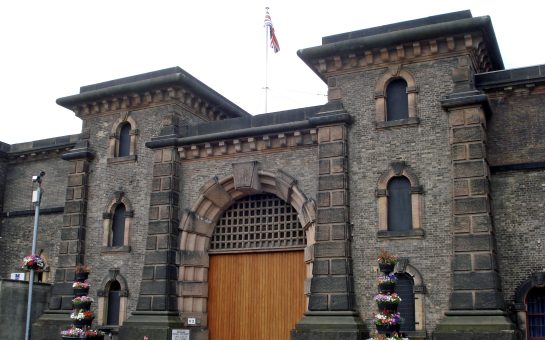

Pentonville Prison might not appear the usual venue for a performance of Shakespeare.

But earlier this year inmates put on a performance there as the climax of an acting workshop run by a classically trained acting troupe.

Shake-ing up rehabilitation

The show saw prisoners use audience suggestions, props and gags to improvise a 20-minute Shakespeare play entitled The Wizard of Disneyland.

Performer Femi said: “You didn’t feel like a prisoner. Having to put on a production for people while you’re inside. It takes you out of the prison environment.”

The workshops were run by Shake It Up, a Shakespeare improv troupe which has toured and performed internationally.

They used acting exercises with the group similar to those they use themselves.

These included bringing in both male and female stock characters for the group to play.

Playing female characters might seem at odds with the macho environment of prison.

However, Femi described how the group’s confidence grew with the sessions.

He said: “It’s quite daunting. You’re with a bunch of guys, some of who you don’t know. And you’re supposed to just improvise and act like a romantic.

“But they build a safe atmosphere. As soon as one of the guys from inside decides to do a female character then it makes it easier for everyone else. By the end, everyone was able to do whatever they wanted.”

Advocates for prison arts say that learning to act or paint can instil humanity and purpose into the sometimes bleak prison life, and improvisational acting can allow inmates to tap into emotions and develop soft skills that can help them deal with tough situations.

Research has shown that prison arts can reduce disciplinary actions inside prison.

A study in California showed that the reoffending rate for those who completed The Actors‘ Gang Prison Project was just 11%, compared to the state average of 50%.

Ed Kaye, a performer and music director for Shake It Up, believes there’s great value in the workshops.

He said: “There’s loads of transferable skills in improv.

“It was sad asking them why they signed up and some said: ‘I just wanted a reason to get out my cell and do something’.”

James Dart, artistic director of the group, was impressed with how imaginative and enthusiastic the prisoners were.

He explained: “At first they were shy.

“But when we started improv games, they grew into it. When they were pushed, they responded really well.

“Several of the inmates said acting allowed them to feel human again.”

Education is the key

Femi became involved in a range of rehabilitative and educational programs whilst in prison.

He added: “My philosophy whilst I was in was just do as many activities as possible. I knew that I couldn’t sit around waiting for time to pass.

“I pushed and pushed to get into education.”

As well as Shake It Up workshops, Femi took up art and design classes, and became a reading mentor to other prisoners.

However, it was a project studying criminology which Femi said benefitted him the most, as it gave him a sense of not being in prison.

The project, run in partnership with the University of Westminster, saw ten students come into Pentonville and study a criminology module alongside ten prisoners.

The program aims to give prisoners an experience of higher education and is now run remotely due to coronavirus.

Jose Aguiar, a prison educator at Pentonville, helped organise the program.

“The feedback I’ve had is people say, ‘I thought education was not for me and now I’ve found myself engaged and able to discover potential that I thought I didn’t have’,” he said.

“This can provide the spark for them to carry on studying and progress.”

Femi also believes educational classes improved his mental health.

He said: “It was a major help for me just getting through that period.

“Having those moments each week was something to look forward to. It was a complete break from being on the wing.”

A recent report by the chief inspector of prisons found 90% of the UK’s prison population suffer from mental health problems, often linked to time spent in cells.

The report found 19% of adult male prisoners were out of their cells for less than two hours a day.

Restrictions due to coronavirus have limited this time further, sometimes to just 30 minutes a day.

In his prison memoir A Bit of a Stretch, Chris Watkins recalls teetotal Muslim inmates at Wandsworth Prison so desperate to get out of their cells they joined Alcoholics Anonymous so they could attend meetings.

Other inmates claimed to be simultaneously Catholic, Jewish and Buddhist to get access to various religious services.

Jose also works with the Prisoners’ Education Trust, a charity that aims to provide more opportunities and improve education for prisoners.

He said: “Education is so important because it’s the best tool that we have to move people away from crime.

“Education ends up widening horizons and bringing new opportunities, so prisoners can see their futures in different ways.”

A struggling system

Prisons aim to rehabilitate inmates so they don’t inflict further harm on society.

The reoffending rate is, therefore, a useful indicator to determine if a prison system is functioning effectively and when judged by this metric, the UK prison system performs poorly.

Britain has the worst reoffending rate in Europe, with 48% of prisoners being reconvicted within one year of release.

With a spiralling suicide rate, increasing prisoner self-harm and an overcrowded prison population, which has almost tripled in the last 50 years, it is clear there are serious systemic flaws.

Chief Inspector of Prisons Peter Clarke said in his 2019 annual report: “Far too many of our jails have been plagued by drugs, violence, appalling living conditions and a lack of access to meaningful rehabilitative activity.”

The prison system is not helped by political inconsistency, as six different ministers have held the role of Justice Secretary in the last six years.

Given the strength of public opinion on crime, spending money on prisons is a divisive issue.

However those who believe prison should be only punitive, must question whether taxpayer money is being well spent.

The cost of reoffending is estimated at £18bn, more than 3 times the total prison budget.

Each prison place costs £37,000 annually, which equates to £666m for the extra 18,000 places that the government plans to add in the next five years.

In contrast to the UK, Norway invested heavily in prison rehabilitation 20 years ago.

It now has one of the lowest recidivism rates in the world, with just 20% of prisoners reoffending in the two years after release.

In the UK, it’s reported that in 45% of male prisons in 2019, recommendations for rehabilitation were not reached.

Hope for the future

There are signs that the success of creative projects has led to increasingly innovative approaches to rehabilitation.

The Anne Frank Trust has been involved in training Pentonville prisoners to become exhibition guides.

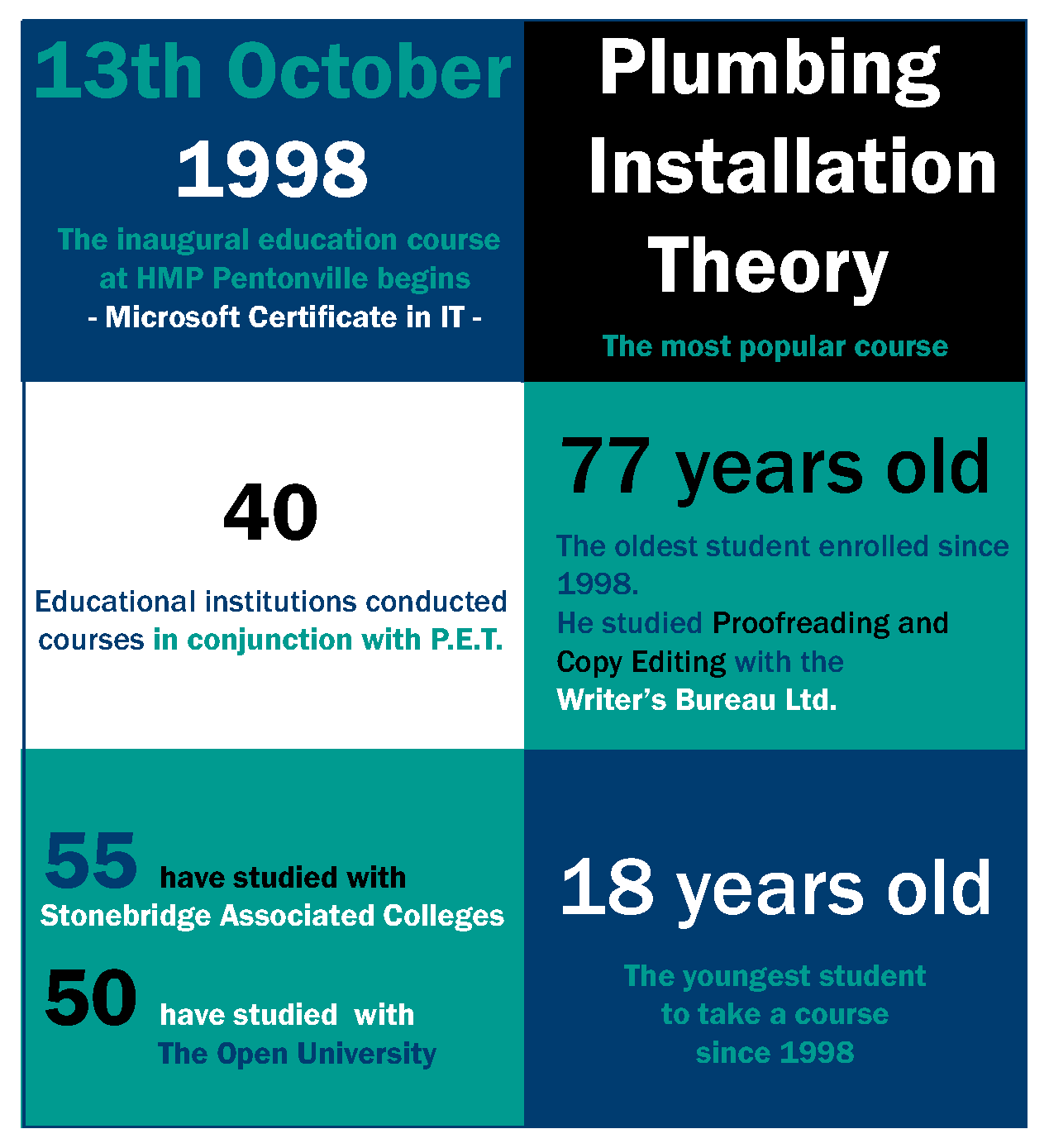

Inmates recently celebrated the anniversary of Pentonville’s 30-year partnership with the Prisoner’s Education Trust, by creating a commemorative book, featuring written pieces and artworks, some of which are featured here.

Shake It Up also plans workshops at other prisons when the pandemic allows.

Jose believes education has a transformational role in prisons.

He said: “It’s really important to move prisoners away from a criminal identity.

“All these programs play a big role in that. With that new identity, they can be an actor, a student, a citizen.”

After leaving prison, Femi became involved in Liberty Kitchen, a social enterprise producing street food made and sold by prisoners and ex-prisoners.

“It’s such a practical way of helping people transition when they get out,” he said.

He’s also in contact with the Prison Reform Trust, a charity working to improve conditions for prisoners and their families.

Its initiative the Prison Policy Network gathers and publishes prisoner opinion on issues that affect them.

Femi added: “It’s really affirming for people inside. You feel like you’re being heard. To see it in black and white you know people are going to know what it’s really like.”

Looking ahead, Femi aims to continue capitalising on all the opportunities offered to him.

“It was my approach inside and so many doors are opened now I thought why not carry it on outside?” he said.