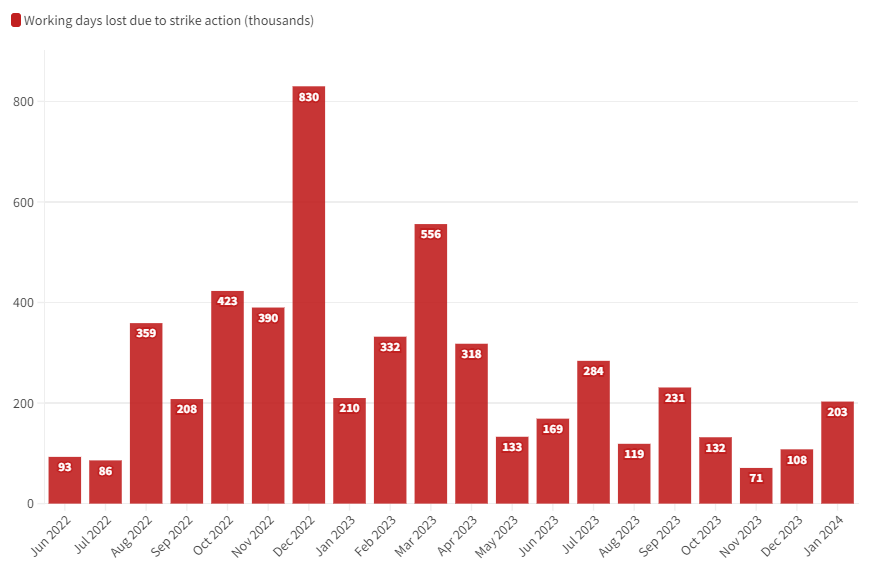

The number of working days lost to strikes in the UK has risen to more than five million in a 20-month period, new data suggests.

The figures, released by the Office for National Statistics (ONS), show that the current period of strikes in the UK are at the highest levels seen in 30 years.

The first wave of these strikes began in June 2022 when the Rail, Maritime and Transport union (RMT) first went on strike over pay, jobs and conditions and since then industrial action has been growing.

The last couple of years have seen high-profile strikes from barristers and teachers, university lecturers and professional staff to nurses, civil servants and postal workers.

The workers striking, although employed in different industries and roles, have found common cause in their decision to strike for better working conditions and pay that is at least in line with inflation.

This comes as the cost of living crisis and high inflation rates have seen steep price increases in everything from rent to groceries.

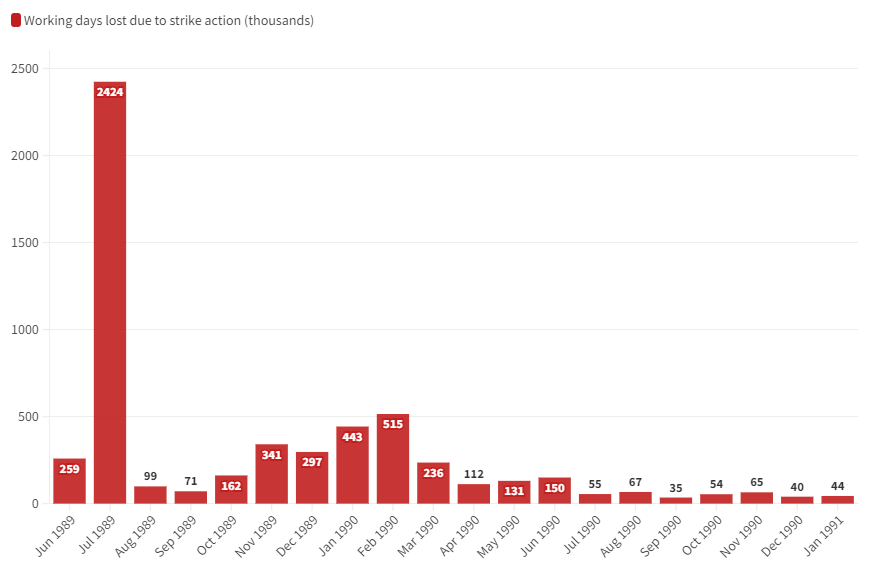

The number of UK working days lost to strike action in the recent period of industrial action has almost matched that carried out between June 1989 to January 1991, when 5.6 million working days were lost to worker’s strikes.

Figure two: Record period of 20-month strike action between Jun 1989 to Jan 1991

In July 1989 the industrial action peaked with nearly two and a half million working days lost, in a month when the forerunner of the RMT, the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR), completed their sixth one-day strike action for better pay.

The strike was successful, with the NUR receiving an 8.8% pay increase, successfully securing the above inflation salary that they were negotiating for.

So More than thirty years on, why is strike action growing to levels that reflect the industrial action of the 1980’s and early 1990’s?

Darren Jones has worked at the University of Sussex for over 20 years in information and web content roles.

Last year he decided to strike for the first time, after having been a member of a union for many years, citing large restructures within the university as one reason.

Jones said: “In the past I must admit, in the previous ballots I haven’t voted. I think I felt, actually, I’m doing all right and I kind of understood the pressure that the university was under.

“The money aspect isn’t as much as a motivation for me as other aspects I suppose, which is partly what I think is different this time about it.

”The way it happened to people, losing their jobs completely, being moved with no thought whatsoever, no negotiation, no consultation. It just felt like the straw that broke the camel’s back, I suppose.

“It just kind of hit home suddenly, you know? I don’t mean anything to anyone in positions of power. And if I could make a stand in some small way, a personal stand, but also with everyone doing that, with their own motivations for doing that, it kind of felt like I’d reached that point.

“The austerity that’s happened and failed over the last 15 years is utterly key to the surge in strikes I think and the COVID situation kind of exacerbated things as well, or brought things to a head in terms of how we felt as a collective, as a country, and how we dealt with that.

“I feel like part of the action generally may be around the privatisation of the public sector. I think as a worker within that environment you just have enough, ultimately. And it’s become clearer that that’s happening.

“Obviously everyone knows about the NHS, and we’ve seen the nurses striking for the first time ever. Schools have been going through the same thing with being pushed towards academies, the trains have been going through this for years.

“I think it’s a combination of things, the public sector being privatised, mixed in with the austerity and all the services being cut and everyone having to do more and COVID being thrown like a bombshell into the middle of it as well. I think it just caused a perfect storm.”

The recent strike action by the RMT culminated in a deal at the end of November last year when members voted to accept an unconditional pay offer and no compulsory redundancies until the end of 2024.

Some industrial action is still taking place in some parts of the rail network and while some deals have been met in other sectors, many unions are still engaging in strikes and industrial action is ongoing for many.

Jones added: ”I guess you also look at other people doing it, you look at the trains and you look at the nurses and you think ah they’re doing it. It did feel like a little groundswell.

“For me, it’s about taking a stand, I think, and maybe the actual impact isn’t as important as actually just saying, no, I’m not going to do it. I’m not going to stand for this anymore. I’m just going to stop. And maybe it doesn’t matter what I do when I’ve stopped and what I do after I restart.”

Featured image: Tak-Kei Wong on Unsplash