Jay Burgess

September 7 2020, 15:30

Follow @SW_Londoner

The number of those serving controversial indeterminate sentences for public protection has plateaued due to a sharp rise in recalls and continued slowing of releases.

When the numbers of both unreleased and recalled IPP prisoners are combined, MOJ figures reveal that the total IPP population stands at 3,328 – a decrease of only 3% in the last year, the smallest drop since 2015.

This follows a period of steady reduction in the IPP population from 6,080 in 2012, when the sentence was banned, to nearly half that today.

The recent slowdown is due to a sharp increase in the number of recalled IPP prisoners this year, up from 186 in 2019 to 245 in 2020 – a rise of 31%.

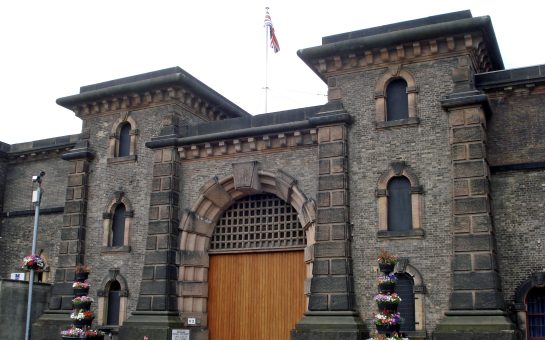

Recalled IPP prisoners are placed straight into prison without trial and will not see the Parole Board for either 28 days after being detained, or within 12 months of their last board review. According to Chief Executive of the Parole Board Martin Jones in 2017, around 60% of IPP recalls are due to the breaking of licence conditions – rather than for committing a further offence – and are rereleased.

In June the Parole Board and the Ministry of Justice said they had developed progression regimes at four prisons to help speed up IPP releases, and increased access to rehabilitation courses.

But Donna Mooney, a vocal campaigner whose own brother committed suicide in 2015 whilst serving an IPP sentence, does not think this is enough.

“Whilst there have been some new progressive regimes, they are for all prisoners, not just IPPs,” she said. “Waiting lists are long and prisoners might not be accepted onto them.

“Also, the MoJ does not track how many IPP prisoners are on these regimes, nor their success rates. How can the success of an action plan be judged if there is no record of the number of people successfully being released from it?”

One London-based senior probation officer, who did not wish to be named, said that recall decisions were inconsistent due to the varying experience and personal biases of officers assigned to prisoners. He also highlighted low staff retention rates which result in higher caseloads and more mistakes.

Simultaneously the number of released IPP prisoners fell from 608 in 2018 to 346 in 2020 – a drop of 43% in two years.

IPP sentences were introduced in 2005 by Labour to target dangerous offenders. Once IPP prisoners serve their term (or ‘tariff’) they are not released until the Parole Board deems them safe.

Due to the misunderstanding and overuse of IPPs, thousands of prisoners became trapped in prison without access to rehabilitation courses, unable to prove they were no longer a risk to the public. The sentence was banned from being used by the courts in 2012.

In 2014 David Blunkett, who oversaw the implementation of IPPs, expressed his ‘regret’ over the ‘injustices’ they caused; last year in a cross party debate both Conservative and Labour MPs condemned their legacy. However, retrospective re-sentencing has never been enacted, despite consistent calls from some MPs and prison reform campaigners.

This means that today, of the 1,969 IPP prisoners who have never been released, 94% have finished their original tariffs. Of these, over half (56%) were given an original tariff of under four years, meaning that 1,107 unreleased IPP prisoners are currently 5-15 years over-tariff, with no release date in sight.

The psychological toll of having an unknown release date is well documented. Prison Reform Trust’s 2019 report found that IPP prisoners were over two-and-a-half times more likely to self-harm than the rest of the prison population; last year, a total of 1,306 self-harm incidents were recorded for every 1,000 IPP prisoners.

If the trend continues and recalls continue to surge then next year could see the IPP population grow for the first time since 2011, before the sentence was abolished.

When asked for comment a Ministry of Justice spokesperson said: “The power to recall is vital to protect the public who rightly expect the most serious offenders to be imprisoned.

“These types of prisoners were deemed by a judge to pose a high risk to the public and are only released after they demonstrate to the Parole Board they are no longer a threat.”