Emma Guinness

July 6 2020, 17.40

Follow

@SW_Londoner

People with mental ill-health have struggled to access support during the pandemic due to furloughs, poor advertising of services and underlying issues.

In April, the National Mental Health director Claire Murdoch appealed to the NHS in a letter for the establishment of a free-to-use mental health telephone support lines during the pandemic.

While hotlines were quickly established, Murdoch told the Independent in June that the number of people seeking help during the pandemic has dropped, which could reflect the fact that the primary options advertised to those suffering on the NHS website are the Samaritans and 111.

NHS advice during lockdown told people to only leave the house for ‘any medical need, including to donate blood, avoid or escape risk of injury or harm, or to provide care or to help a vulnerable person’.

This meant that those struggling with their mental health had no clear path to access help beyond the emergency options.

OCD sufferer Maximillan Hawker said of the pre-pandemic mental health care system: “I’ve accessed the NHS for OCD support on multiple occasions over two decades and, on every occasion, there has been a different outcome – some good, some bad. It’s like a lottery for the mind.”

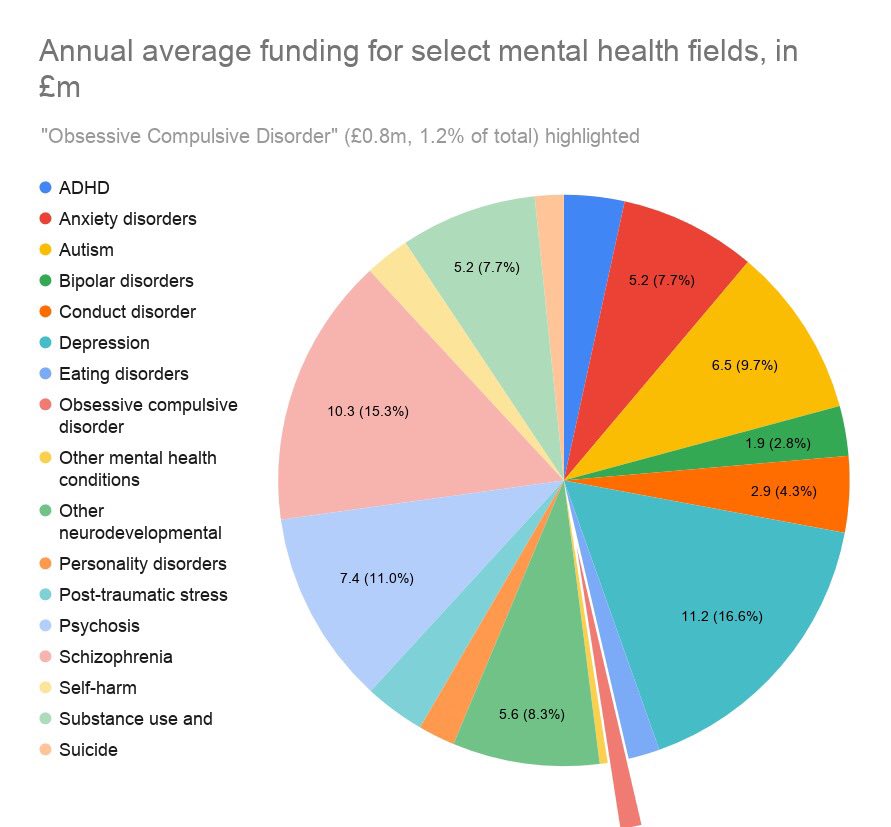

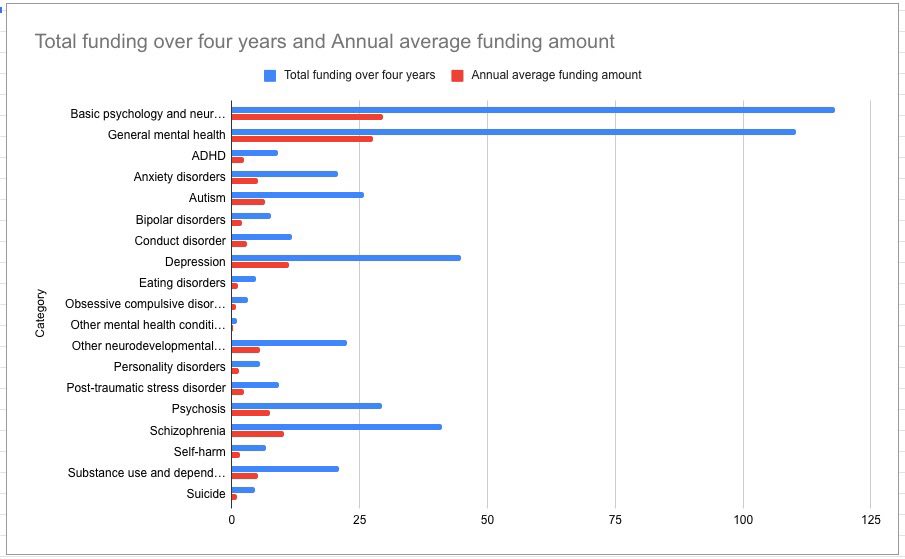

A 2014/17 MQ report into British mental health funding found that depression and anxiety disorders affect 9.7 million Brits every year, but funding into research is just £1.78 per person.

The chart below shows the disparity of investment across conditions, with OCD receiving an average of £0.8 million a year despite a clinical review stating it’s the fourth most common mental disorder, making it the lowest invested in common condition.

The picture of investment in millions across a four-year period paints an even clearer picture.

Mental health advocate and peer support specialist Chrissie Hodges said the barriers sufferers of mental ill-health face in finding therapists who do specialised treatment at an affordable rate have been exacerbated by the pandemic because of redundancies and furloughs.

One British OCD sufferer said she had been placed on a waiting list for CBT for OCD last August, but her access to treatment has been put on hold because of the pandemic and her full-time job, which made accessing treatment at a suitable time difficult.

She said that she felt like she had been put ‘out to sea without a life jacket’ during the pandemic when it came to her mental health care.

Under the current system, specialist care can only be accessed through a GP referral, and it comes with notoriously long waiting lists which can cause people to deteriorate further.

Nick Sireau, the co-founder of Orchard OCD, which is crowdfunding research into new treatments during the pandemic, said: “At the moment mental health services are overwhelmed. In places like Cambridge where I live, there’s an 18-month wait to access psychological services. In that time people’s OCD and mental health will generally get worse.”

While she discovered through friends that online consultations are available, she was unaware this help existed because of a lack of publicity.

When emergency care becomes the only option, which it may be for many during the pandemic, it is costly to the NHS, with the Independent reporting that an emergency call costs around £7, and it is £180 to send an ambulance, and £233 to visit A&E.

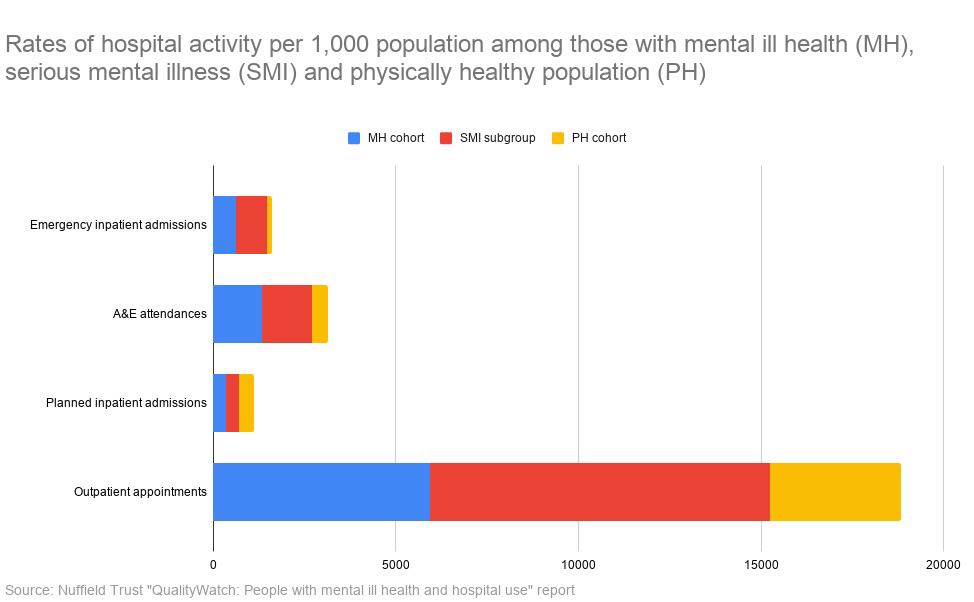

The Nuffield Trust found it had a higher rate of preventable emergency admissions for people with mental ill-health before the pandemic. In 2013/14, it had 3.2 times more A&E attendances and 4.9 times more emergency inpatient admissions.

Featured below are the Nuffield Trust’s QualityWatch findings, which looked at hospital activity in a given year per patient subgroup using Hospital Episode Statistics from the NHS.

They are split into the mental health cohort ‘MH cohort’, the serious mental health cohort (those who had at least one inpatient admission or outpatient appointment with a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or psychosis) ‘SMI subgroup’, and the physically healthy cohort ‘PH cohort’.

The Nuffield report found a correlation between deprivation and emergency care use, with the most deprived people with mental ill-health visiting A&E 1.8 times more than the least deprived in 2013/14.

But the care provided at A&E is not consistent or a long-term solution, which could lead to multiple admissions.

People experiencing a mental health crisis at A&E are referred to liaison psychiatry services, which consist of mental health nurses, psychiatrists, and administrative staff.

Although they can have additional staff including psychologists and psychological therapists, this is not guaranteed, meaning that the extent and type of help available is once again a lottery.

People who attend A&E may be referred to a local crisis resolution and home treatment team (CRHT), however, like the liaison psychiatry services, they only provide short-term assistance.

Mr Hawker, who is also a children’s social care worker, added: “I have a lot of experience supporting people accessing emergency support for mental health crises. The policy tends to be one of dismissal with people ejected from A&E unceremoniously.”

One woman who attended A&E for a crisis during the pandemic wrote in the iPaper that she was free to leave after a discussion with a nurse who offered no immediate support beyond crisis hotline numbers.

The MQ report revealed research into mental illness receives less than 5% of NHS funding, concluding: “These amounts are worryingly low,” as “investment in these areas can directly impact and improve lives, leading to tangible change.”