The Minister for Safeguarding, Jess Phillips, recently announced that victims of stalking will now be told the identity of their abusers – part of a new set of government proposals to give more protection to victims of stalking in England and Wales.

It comes as the Metropolitan Police recorded a slight decrease in stalking and harassment over the past year – but not enough to indicate a significant trend, with reporting rates still likely low.

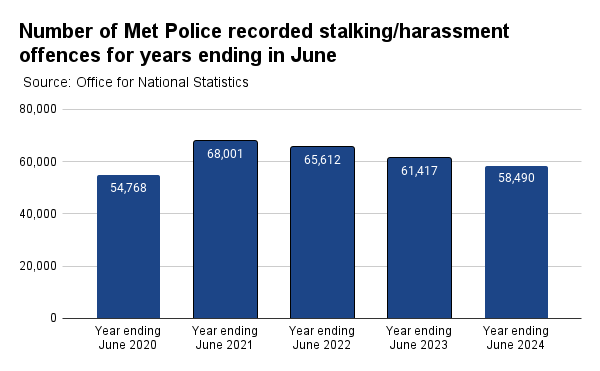

New figures reveal that the Met saw a 5% yearly decrease in recorded stalking and harassment offences.

There were 58,490 recorded stalking and harassment offences in the year ending (YE) June 2024, compared to 61,417 up to June 2023, according to data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

The statistics, released on October 24, also reveal an 11% decrease in recorded stalking and harassment offences for England and Wales – meaning rates have not decreased in the capital as much as elsewhere.

The report uses data from police recorded crime and the Crime Survey for England and Wales.

Yet the ONS cautions these changes are not significant – and the experience of victims suggests that stalking and harassment are just as great a problem as ever.

“They might be too embarrassed to go back to the police”

Emma Davey was stalked and harassed for three and half years by her ex-partner after she walked away from their relationship. One of the police forces she dealt with was the Met.

She said: “He was very coercive and controlling in the relationship where he would isolate me, track me by my car and my phone and put cameras in the house. When I left the relationship, that mentality stayed where he still felt he was entitled to know what I was doing.

“He made up fake accounts under the name John Smith and would follow me via those accounts on Instagram, Facebook and TikTok. When I was in the press talking about narcissistic abuse I looked in the comments, which we are told not to do, but I did.

“There was a John Smith that was stating that I was unqualified, a prostitute and a stripper. He would constantly ring me and he sent indecent pictures of me to my dad and my mum on different occasions.”

It escalated to the point that Emma’s ex-partner began leaving flowers at her house daily and he eventually turned up at her property and was trying to bang down the door to get in.

Despite police turning up and arresting him, the behaviour repeated, but when Emma told the police they just said they would call her ex-partner and tell him to stop.

“It’s very demeaning having to keep going to the police and be told ‘he hasn’t done anything wrong’,” Emma said.

“I had to go through more abuse for the police to do something about it and my case may have never gone any further if I wasn’t as persistent as I was.”

When asked about the decrease in recorded stalking and harassment offences, Emma said she doesn’t believe it is accurate because many victims are too scared to approach police or withdraw due to lack of support.

She added: “I could have never phoned the police again, because I may have felt humiliated or felt like I was the one in the wrong. I think if that’s the type of treatment victims are experiencing, then they are going to be too embarrassed to go back or might not trust the police.

“I did an interview with [Victims’ Commissioner] Claire Waxman a few months ago and we were both talking about stalking. It’s because the lines are so blurred that the police don’t even know the difference between harassment and stalking.”

Jan Berry, Co-CEO of Protection Against Stalking, said there are common crossovers between stalking and harassment behaviours, which can often lead to crime misidentification – impacting recorded offences.

She said: “The behaviours are the same in many cases. What is different is the motivation of the stalker. To be stalking, the behaviours need to be fixated, obsessive, unwanted and repeated.

“Unwanted and fixated applies equally to harassment, but fixated and obsessive does not. Too often stalking cases are recorded as harassment due to lack of knowledge, poor investigation or recording practices.”

Emma’s ex-partner was eventually charged with coercive and controlling behaviour.

Despite receiving a prison sentence of 19 months, he was released after six weeks and has since been charged and prosecuted for non-fatal strangulation and assault by beating to another victim.

“Sometimes stalking is being charged as harassment”

Dr Alan Underwood, lecturer in forensic mental health at Queen Mary University of London, explained there are links between coercive and controlling behaviour and stalking, particularly where it’s an ex-partner.

His concerns as a practitioner and an academic working in the field, is that stalking behaviour often gets lost in terms of identification and management as a result of coercive and controlling behaviour.

He said: “The risks for stalking and coercive control are different and serve different functions. They need to be identified differently and I imagine where it’s an ex-partner case, that stalking behaviour has been seen as coercive control.

“Whereas it might be coercive control and stalking rather than it just being one kind of thing. Other pattern offences are being pulled in and sometimes stalking is being put up as and charged as harassment.”

In addition to misidentification, a joint investigation into the police response to stalking by His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services and others, noted that Crime Survey data suggests many incidents could be unreported to police.

This is evidenced by changes to police recording rules by the Home Office and that police recorded crime ‘excludes offences that are not reported to, or not recorded by, the police’.

The ONS also described the yearly change in figures from the Crime Survey as not being ‘statistically significant’.

In the YE March 2023, there were 61,563 Met recorded offences and in the YE March 2024 it had only dropped by 2% to 60,026.

According to the London Stalking Review by Victims’ Commissioner Claire Waxman, when national stalking rates increased by 11-fold between 2016/17 to 2022/23, London rates still remained low at 6.98 offences per 1,000 people, compared to England and Wales at 11.71.

Confidence in the system

For the YE June 2024, the number of recorded stalking and harassment offences in London as a whole was 58,628 (including City of London Police).

Dr Underwood explained: “There are a lot of different factors that come together and one of them is confidence around reporting. The trust and confidence issues the Met has had particularly in recent years, I think that’s potentially one thing.

“If people are recognising stalking, they are not feeling confident to report because perhaps they feel they might not get a satisfactory outcome.

“That’s the sort of work some of the specialist units and some of the training that’s been developed with the Met through the Mayor’s office. But that may be one aspect.”

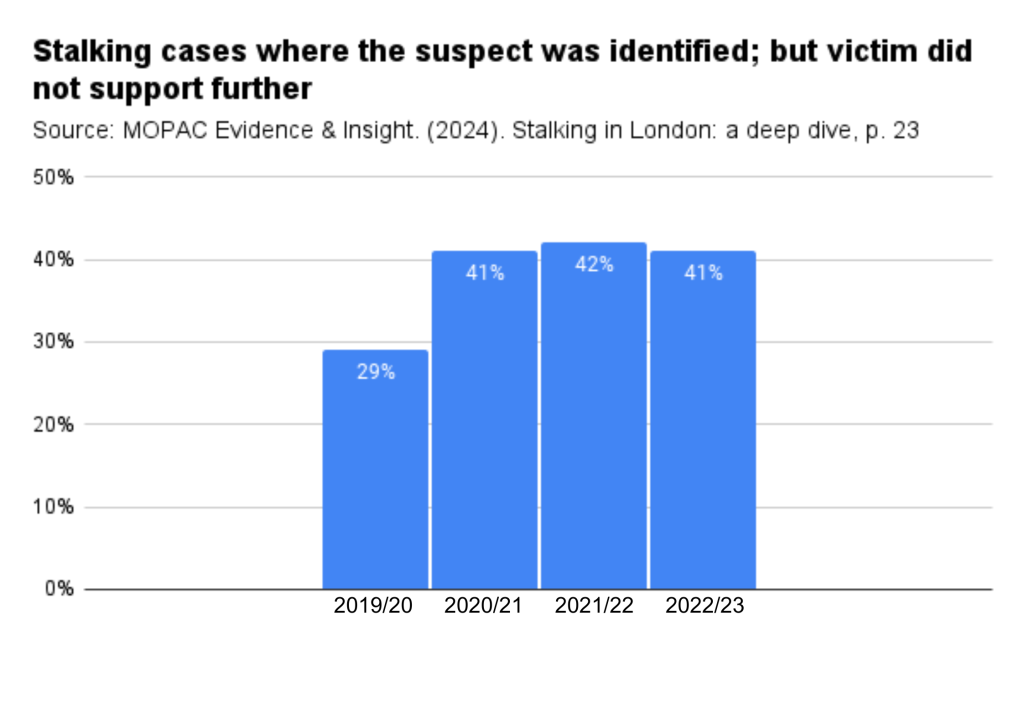

The Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime (MOPAC) has also gathered data that points to the issue of evidential difficulties. Known as Outcome 16, it is where the suspect had been identified but the victim did not support or had withdrawn support from police action – it increased between 2019/20 and 2020/21 and has remained consistent since.

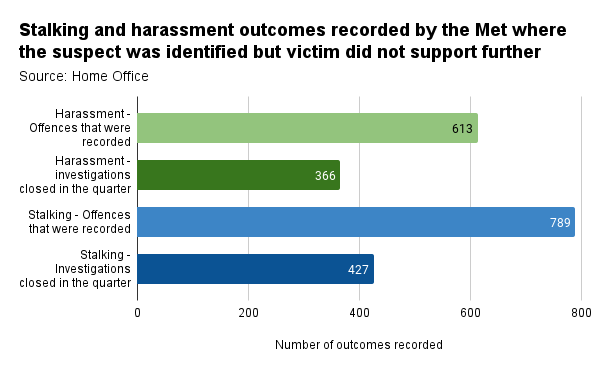

More recent statistics from the Home Office show that from April to June 2024, the Met recorded 789 stalking offences and 613 harassment offences where this was the outcome. For investigations closed in the quarter with the same outcome, there were 427 stalking offences and 366 harassment offences.

Commenting on evidential difficulties, Dr Underwood, said: “I think there are a range of reasons and what we hear most frequently is the victims just want the behaviour to stop.

“In cases often where it’s a non ex-partner, there’s a perception that perhaps the person has some vulnerabilities or difficulties and needs help rather than the prosecution.

“Reluctance sometimes can also be about the current court system and the amount of time that it takes for cases to come through.

“A guilty plea is lengthy and that’s a huge burden on the victims. We’re looking at a couple of years.”

Positive signs

It is clear a lot of work still needs to be done towards stalking and harassment cases, but it is moving in the right direction.

In September this year, two Met Police officers received National Police Chiefs’ Council awards, in recognition of their work in detecting behaviour changes in stalking perpetrators.

According to the force at the time, recent figures had shown reoffending in more than 300 high-risk offenders was reduced by 78% because of the officers’ work.

Commander Kevin Southworth, lead for public protection in the Met, added: “The Met is transforming the way we protect the public from harm, better targeting predatory offenders and identifying stalkers as early as possible.

“We know we’ll be judged by our actions and we’ve already made some progress – using technology to investigate these offences and increase the number of stalking protection orders since 2022.

“There’s more work to do and we’re committed to working with our partners, including the Suzy Lamplugh Trust, to tackle this awful crime.”

For the more serious s4a offence (Section 4A of the Public Order Act 1994), which involves intentionally causing harassment, alarm, or distress, the Met recorded a 40% increase since April 2023. At the same time, s2a offences where pursuing a course of behaviour that amounts to stalking decreased by 60%.

The force believes the decrease shows it is getting “increasingly better at recognising the profound harm and fear caused to victim survivors and hence also pursuing the more serious charge of s4a more often than before where appropriate”.

Police forces have also begun publishing their stalking action plans as required in response to the findings of the police super-complaint submitted by the Suzy Lamplugh Trust (on behalf of the National Stalking Consortium) in November 2022.

Anyone who has been affected by this report or needs further advice, can contact The National Stalking Helpline on 0808 8020 300.

Feature image source: João Jesus on Pexels