By Naomi Curston

July 28 2020, 14.00

Follow @SW_Londoner

“Sadly, over time, some stories are retold and some stories in history are felt important, and some just disappear.”

Linett Kamala is talking about the erasure of Black British history, specifically the activist history of the Notting Hill Carnival and Kelso Cochrane.

The artist, educator and carnivalist, 50, works all over the capital, and her latest artwork Kelso & Carnival brings Kelso’s story back to the centre stage.

Kelso Cochrane was born on the Caribbean island of Antigua, and he was part of the Windrush Generation when he came to London in 1954.

His murder at the hands of racists five years later happened amidst a climate of extreme violence against the city’s new Caribbean residents.

His funeral made national news and his death became a catalyst for small community-led events in North Kensington that would one day become the Notting Hill Carnival.

And yet, despite that, even seasoned carnival-goers may not know who he is.

“This cannot disappear,” Linett said.

Kelso & Carnival, then, is to ensure this history’s visibility.

It has another purpose too – it combines art and carnival with Linett’s other love, education – designed as it is to be an inspiration for young people entering the Black Cultural Archives’ Windrush Waves competition, for which Linett is one of the judges.

The competition, open until August 2, asks young artists to respond to the stories of the Windrush Generation through visual art, photography, poetry or music.

Winners will receive expert mentorship and the opportunity to exhibit their work.

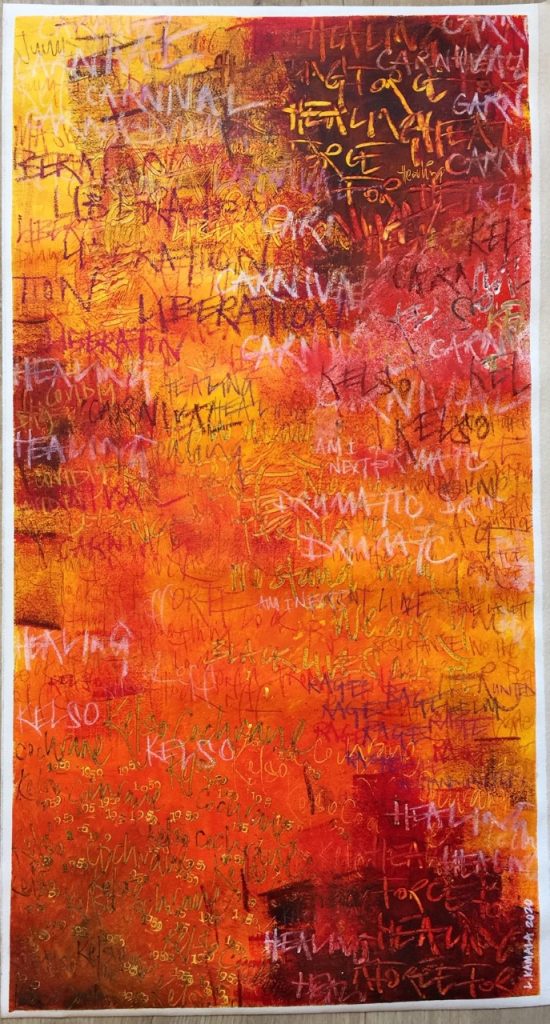

Speaking about Kelso & Carnival, Linett identified it as ‘freestyle calligraffiti’ – a style she uses in much of her work.

It’s fast, free and emotionally driven, but a lot of research goes into her art too.

“I love researching the project,” she said.

“Academic papers, journalists’ articles, all sorts, I just love, love reading, and I will make reference to that in my work.”

On Kelso & Carnival specifically, she said: “I always want people to learn, to be intrigued to find out more for themselves.

“In this piece I wanted to capture some of the vibrancy – the fire, the energy – so that’s why it’s got the warm oranges and yellows.”

“It’s fast, it’s spontaneous, it’s expressive. There’s going to be words in there, I want it to be that you can see some of the words; sometimes you’re going to look closer.”

Just as the words in her art are an invitation to a deeper meaning, so too are the work’s themes influenced by things that are deeply important to her – this is not just an ode to a random historical event, and her selection as a judge is not a coincidence.

Carnival has mattered to Linett since she was a child.

She is one of the board directors of the Notting Hill Carnival today, but even at 14 she was one of the first girl DJs there on the Disya Jeneration sound system, which as an adult she still helps to run.

She also gave a TEDtalk called ‘Carnival a force for healing’ in 2019 to two sold out audiences.

Similarly, the Black Cultural Archives specifically and education in general have both been incredibly important to her, far prior to becoming a judge for Windrush Waves.

“I loved history at school but I wasn’t taught about Black history in terms of quite recent Black British history,” she said.

“All too often in British schools, the only thing historical about someone who looks like me that’s taught is slavery, and then we leap over to the civil rights in America and that’s kind of it.

“So, like a lot of people, when I got into my 20s I started to find out things for myself, reading, going to meetings and things like that.

“There were amazing meetings happening at the Black Cultural Archives.

“Incredible significant historical figures from Black history were there; you could hear them speak in person.”

Her love for education doesn’t stop with history, however.

Her mother, now retired, was a pioneering SEN teacher, and Linett has always loved learning.

She said: “I was born a teacher. I always knew I wanted to be an educator.”

She went to art college after secondary school, training as a graphic designer, and although she exhibited a little bit in the 1990s, even catching the eye of Charles Saatchi, she knew she wanted to focus on teaching.

By 23 she had achieved that ambition, rising quickly through the ranks, until she became the first Black female head of a secondary school in Brent.

She went on to found Chelsea Academy, which opened in 2009, and was an education executive for a multi-academy trust too.

Linett is still involved in education in many ways – she trains school leaders, and teaches art at GCSE and degree-level – but she’s not where she was once.

“When people ask me ‘why aren’t you leading schools anymore?’ I simply say one thing: racism,” she said.

“That’s it.

“I don’t dress it up anymore.

“I know my credentials; I know how amazing I can be.”

Linett’s experience is not a one off, and the subject is the focus of State of Education, one of the first art projects that she started after she decided to step away from school leadership.

The project is still ongoing – a collection of monochrome calligraffiti artworks.

On why there aren’t more Black school leaders today, she said: “Look at the stories of why we aren’t still there.

“It’s not that there aren’t Black teachers, it’s not that they don’t apply, it’s not that some of them don’t get given the positions.

“Find out about the pattern.”

An NEU report from 2017 gave an indication of what that pattern could be.

It suggested that BME teachers were more likely to leave the profession as they reported lower levels of job satisfaction and higher levels of stress.

It also found that Black teachers in particular were more likely to be labelled as troublemakers or ‘aggressive’ for challenging decisions.

“I meant business,” Linett said. “I wasn’t just ticking boxes. I was about every single child getting the very best, and I meant that, truly. If I had a policy, I tried to make it real, and I would challenge people who wrote things and didn’t follow it up.”

Current and upcoming work

Linett’s exhibition My Heart Will Always Be in Brixton has been at Lambeth Town Hall since September 2019, and is featured on Google Arts and Culture, where it’s been since June 26.

The exhibition focuses on Jamaican-born Brixton activist Olive Morris, who fought against racism before her death at just 27, and who would have been 68 this year.

She also has outreach projects coming up through her art and education company Lin Kam Art, a new commission and plans to mix up VR, art and music.

To learn more, follow her on Instagram.