We’re idolising the wrong fashionistas.

Public figures with stylists and glamour squads have such influence over how they are perceived that it’s surprising when they don’t look good at a red-carpet event. But even aesthetic expectations of the rich and famous are lowering. Forget designer couture because the social media masses want something simpler.

Now, we pore over new paparazzi snaps of celebrities, the more candid the better. Where glamour once reigned supreme, scruffiness sits in its place.

Princess Diana, still a style icon since her death, was famous for her casual pairings of cycling shorts with quirky oversized sweaters, or formalwear with jeans, dazzling the nation with her fantastic ordinariness. Bella Hadid has developed a similar reputation for awkward outfits made cool. She’s the sportswear cupid, pairing every lonely set of ankle socks with its corresponding pair of chunky trainers.

The move towards a more realistic look should be a positive one – but is it actually making fashion more inaccessible?

When we see celebrities dressing like us, it feels like a glimmer of hope. Maybe we can look the way they look; dress the way they dress. Perhaps if our outfits more closely resemble theirs, our lives might do the same. Perhaps we’re also millionaires.

The reality is an outfit is never just an outfit. Fabrics, tailoring, and manufacturing of clothes are crucial to the final impression, and those things cost money. When the lines between ‘us’ and ‘them’ start to blur, we are lured into a false reality in which money poses no problem.

But the London fashion scene is embracing slowness and sustainability – the Zara coat that trickled down from the Céline runway is out, and (get this) individuality is in. The young, fashionable person is becoming someone with a style identity, with purpose behind the way they dress.

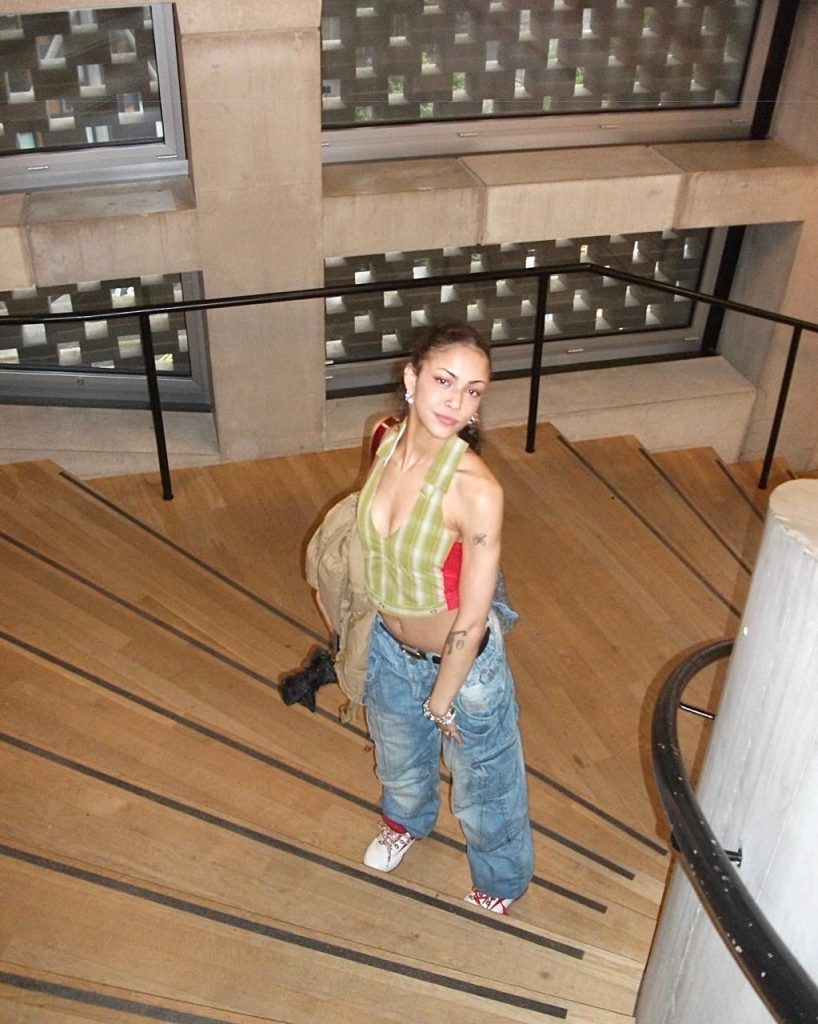

“Celebrities are just faces that brands send pieces to for free. It’s not actually their style,” said 23-year-old Kalli Maria, founder of Mercury 48, a ‘waste management’ clothing brand which puts pieces together from scrap material.

“I really see myself as part of the slow fashion movement. Zero waste comes out of my studio.”

“I keep the rubbish so that I can use it for something in the future and that’s what a lot of my work is – I use old things to make something new.”

Kalli’s pieces are either upcycled or made from old fabric, then she keeps the scraps and makes more clothes, and the cycle continues. Having turned down a scholarship to Parsons School of Design in New York to look after her ill mother, Kalli is making it work. Crafting pieces out of her living-room turned studio space, each project is deliberate and mindful.

“It’s slow fashion. I don’t drop like how a lot of brands do. I might drop one piece every couple of months. At the moment that’s what I can do because it’s a one-woman team.

“When you come from struggle, you adapt.”

And Kalli is optimistic about being young, struggling, living in London, and still noticeably fashionable: “That’s literally me.”

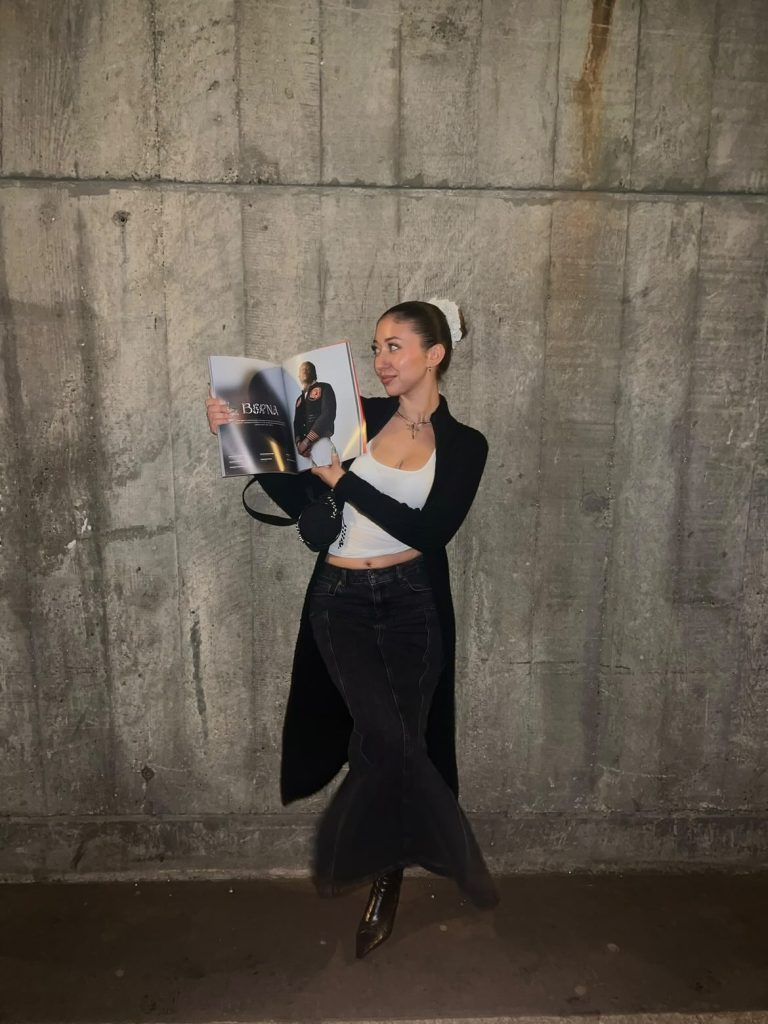

28-year-old designer Clara Chu specialises in custom-made-to-order bags from upcycled household objects. Her brand repurposes anything from toothbrushes to vacuum cleaners and turns them into bright, striking accessories.

“Slow fashion is definitely one of the core ethos of the brand – we produce one collection a year at the moment.

“The concept is one of taking customers onto a bespoke journey which includes a co-creation process and consultation service – it’s not a direct online purchasing model.”

But for those of us who aren’t looking to break new ground, it’s hard to gauge on which side of the line we fall. Do we look to EmRata for style advice, or do we chuck it all out and opt for family hand-me-downs?

Clara suggests there’s a third fashion identity that centres less around the clothes themselves than the attitude we have.

“Style comes from your experience rather than just dressing up. It’s not necessarily about what you wear, it’s about conversations and dialogues.

“A lot of the admiration for celebrities is about their confidence – it’s that we strive for.

“We’ve moved beyond wanting to shop – if you look at accounts posting about celebs, they don’t even tag what they’re wearing anymore. It’s about the story behind them and wanting that lifestyle rather than the actual dress and makeup.”

I asked Clara the same question I asked Kalli – is possible to be in London on a starting salary and still look good? “Absolutely. I created this brand literally using anything I could find, and things deemed to be waste. There’s a lot of reimagining what anything could look like.”

But 26-year-old London-based freelance stylist Andjela Despotovic believes that unattainability plays an important role.

“I do think it’s important to have people that we can get inspiration from,” she says.

“They’re wearing things we can’t obtain, but that’s okay too. You don’t need to wear what Rihanna wore, or have the most expensive bag, it’s just about appreciating the garment even if you can’t afford it.

“A garment can be an art piece itself.”

So, we can admire the Mona Lisa without wanting her above our mantle.

“If you want to wear a lot of different looks then looking good is expensive, but you can re-use and re-style the same pieces in different ways.”

The consensus is that innovation keeps you stylish. And while confidence has always looked good, it’s more about the confidence to dress in a way that reflects your style rather than the act of stepping out with flair.

The role of the fashion idol is becoming less literal and more symbolic: we emulate style rather than copy it, and we admire people’s ability to self-identify through fashion, not the fashion itself.

Trends will always be there, but wearing something radical, jerky, maybe even slightly ugly, and making it look good through an inspired pairing or a determined vision – that’s where the real fashion lies.

Featured image credit: Ayaat Yassin-Kassab