Mental health professionals resist recommending voice-hearers to Hearing Voices Groups (HVGs,) despite increasing popularity and a wealth of evidence they are effective.

According to Hearing Voices Network, a charity raising awareness about voice-hearers and connecting HVGs, between three and 10% of the population hear voices, see visions, or have similar sensory experiences that others can’t have, including all five senses.

Some find these experiences comforting: for example, lonely people might hear hearing voices that become a trusted confidant, or smell the perfume of a loved one who died.

For others voices are extremely distressing, threatening them or causing confusion.

HVGs offer support to voice-hearers, yet University of Bath (UoB) discovered only 30% of mental health professionals were confident explaining HVGs to users.

Six out of the 25 respondents were hesitant to refer service users to HGVs because of lack of understanding. Others were concerned they might not be safe.

As a result, UoB called for further training among mental health staff about HVGs, as the groups’ successes rely on professionals referring service users.

This comes as 27 June Government drafted a bill to reform the Mental Health Act 1983, promising to increase service users’ access to and say in treatment.

What are HVGs?

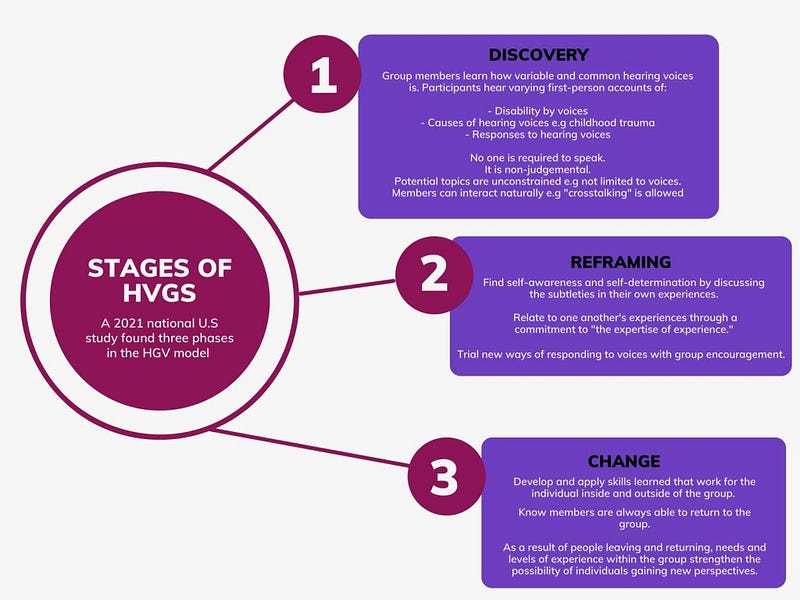

HVGs adopt an “experts by experience” approach.

They search for meaning in auditory hallucinations, sharing stories and understanding individuals’ voices in the context of wider life experiences.

Groups create an equal, curious and non-judgemental space, normalising the voices.

Many HVG proponents reject pathologising hallucinations and unusual beliefs, as they argue mental health systems cause distress, rather than the experiences themselves.

In particular, they recognise diagnoses of psychosis can be disempowering, increasing hopelessness and fear as one of the most stigmatised mental illnesses.

In an autobiography Elyn Sacks, a person living with schizophrenia and Professor of Law, Psychology, and Psychiatry and the Behavioural Sciences at University of Southern California, said of her diagnosis: “Repeatedly, I ran up against words like ‘debilitating’, baffling’, ‘chronic’, ‘catastrophic’, ‘devastating’ and ‘loss.’

“For the rest of my life. The rest of my life. It felt more like a death sentence than a medical diagnosis.”

Sack’s experience is echoed by research into distress suffered by people with first-time psychosis, conducted by Greater Manchester Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust (GMFT.)

One respondent said: “Being told I had psychosis—that’s been the most difficult thing. You know, to be told I was incapable of making decisions. It made me feel a bit insulted, a bit like disappointed in myself as an adult as well.”

Another said: “I think I eventually told my mum what happened. I didn’t want to tell anyone else, yeah, I think I eventually told them what I was feeling and stuff.”

What do first-person accounts tell us?

First-person accounts demonstrate mental health services for hearing voices can cause distress.

However, GMFT, like HVGs, argued psychosis-like experiences are not inherently distressing.

Encounters exist on a continuum with ‘normal’ human experiences, such as one-off events like hearing your phone buzz without a text.

They are no longer believed to necessarily be signs of mental illness requiring pharmacological and psychological treatment.

The prevailing assumption that hearing voices, seeing visions, and experiencing unusual beliefs is distressing is due to: people’s increased risk of suicide, reduced social functioning, and relatively poor clinical outcomes.

A lack of first-person research strengthened this belief, said GMFT.

The groups aim to shift public and professional perceptions of experiences often associated with psychosis as well as voice-hearers’.

They advocate for alternative forms of support.

An alternative type of support

Rather than the voices themselves, loss of control appeared to play in a central role in causing service users’ distress.

Helping people gain more control over their lives would help decrease distress, versus aiming to reduce voices’ frequency and intensity.

GMFT said: “When working with people experiencing [first episode psychosis], practitioners should be mindful of overemphasising the assessment and treatment of psychotic symptoms at the expense of considering wider difficulties.

“Adopting a stance of genuine curiosity about potential sources of distress is likely to be experienced as more helpful by service users.”

HVGs offer a space where members can live with voices with less distress. They help impaired functioning, isolation, lack of social support, lack of hope, lack of self-esteem and power in their own lives, and stigma.

The effect of Hearing Voices Groups

The Melissa Roberts Foundation (MRF) conducted research in an East Sussex HVG, 2004.

Their findings indicate the importance of increasing access to HVGs.

One member said: “Realising you’re not strange, a weirdo, it happens to other people — members of the group have enabled me to normalise and to know you can have a fulfilling life even with voices.”

MRF found a significant decrease in hospital admissions after people attended the group: an average of 39 days in hospital a year fell to eight the following year.

At the beginning of the group on person was in work, six were after.

Though the groups can be challenging, even increasing the voices’ power at times, the overwhelming experience was positive.

A member said: “The voices don’t like it that I’m going to the group and I’m being positive whereas they prefer me to be negative — it’s a way of defeating them so they don’t like it.”

“Regularly attending the Eastbourne hearing voices group has played a major role in my healing process — I dread to think what would have happened to me without the group,” said another.

NHS and Hearing Voices Groups

UoB researchers argued mental health professionals may need further training in order to increase their understanding, as gatekeepers to people’s care.

They found: “Clinical decisions frequently deviate from evidence-based guidance, decisions are guided by their own beliefs, informed by norms and their professional identity.

“Whilst a number of pharmacological and psychological interventions have been shown to reduce individuals’ voice-related distress these are not always effective.

“Evidence suggests it is an individual’s relationship with their voices, rather than the experience itself, which leads to distress.”

This supports HVGs’ philosophy and GFMT’s research.

UoB found the majority of their surveyed professionals believe Hearing Voices Groups (HVGs) are positive.

However, only 25% were aware of the evidence for HGVs and only 30% were confident explaining HVGs to users.

Six out of the 25 were hesitant to refer service users to HGVs because of lack of understanding.

Five expressed concerns about HVGs, including that “there is a fear of HVGs not being ‘safe’.”

Though most believed the groups would help services users, some did not.

UoB suggested practitioners’ beliefs may arise from HVGs accepting alternatives to the medical model.

Fears include that HVGs support any interpretation of voice hearing, including rejecting traditional psychiatric treatment.

Today HVGs operate in over 30 countries.

There are 180 groups in the UK, more information can be found at the Hearing Voices Network website.