By Ben Turner

May 7 2020, 19.00

Follow @SW_Londoner

“One day my mum phoned to ask me: ‘Do you know how to clean up tear gas?’”

There had been protests outside, and the smoke had spilled in from the streets below Hannah’s mum’s apartment.

It had been a powder just a few moments before, enclosed in scorching-hot shells shot from federal riot guns.

Dense and vinegar-smelling, tear gas stings the eyes and burns the skin.

Taking in a lungful sears the throat and rapidly tightens the chest.

It is overwhelmingly painful, by design.

The smoke in her apartment was only enough to make her eyes water, so Hannah’s mum closed her window and patiently waited for it to disperse outside before letting it out.

China National Day on October 1 was an unremarkable morning in Hong Kong.

More than 16,000 rounds of tear gas and 10,000 rubber bullets were fired by the city’s police over the second half of last year, in what protesters characterise as the Beijing-controlled government’s response to their demands for democracy.

Dissent against a proposed bill allowing extradition to the mainland was fast evolving into a quasi-nationalist movement.

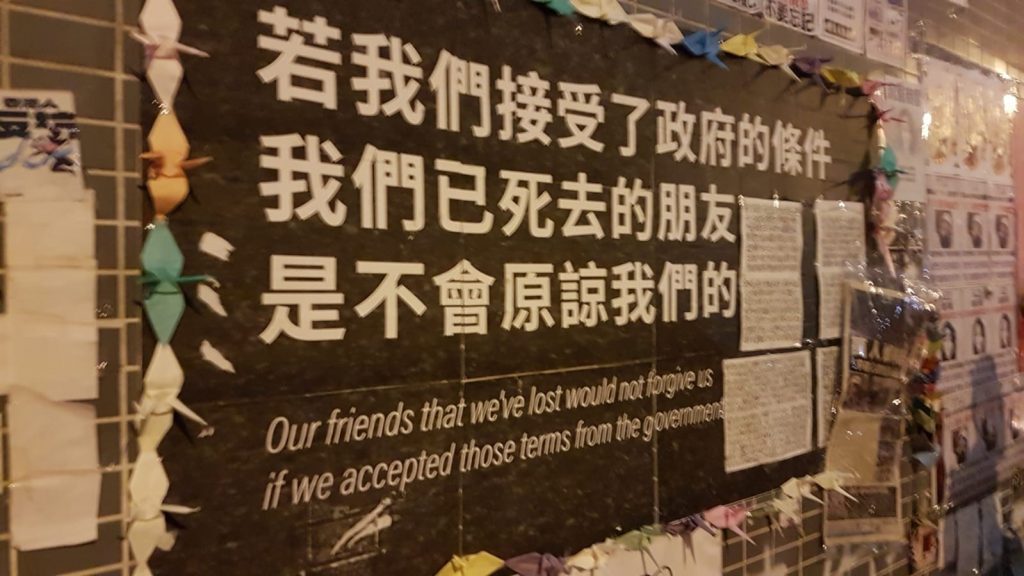

Offshoots from the two million protesters had created their own national anthem and even advocated for independence. How they would achieve these goals was unclear, but the principles at stake – democracy and freedom of speech – were invoked with fierceness and clarity.

Yet by the time the smoke had been let out of Hannah’s mum’s apartment that day, the city had already been sent on a much darker path. That afternoon was the first occasion an officer had fired a live round during the protests, into the chest of Tsang Chi-Kin, an 18-year-old high school student.

“That was the turning point for me,” said Mic, a Hong Konger in his 30s.

“My dad is a retired police officer, but the media caught them planting evidence on that boy. I’ll never trust the police again.”

Mic’s October 1 disavowal was one of many ruptures to emerge from a deepening trend of inter-generational conflict all over the city.

Parents and children had always disagreed over the merits of democratic liberalism versus closer alignment with Beijing, but suddenly their disagreements became hostile.

Charities sprung up around the city to support pro-democracy children turfed out onto the streets by their parents. Many families simply cut off contact.

“My family is splitting apart,” Mic said. “My mum accused me of accepting money from the Americans to go protesting.”

Tsang made a miraculous recovery before being charged with rioting and assaulting the officer who shot him. His trial has been postponed until next month after the beginning of another fight Hong Kongers have the misfortune to be on the front lines of – the COVID-19 epidemic.

It was a crisis that both government and civil society were prepared for after the 2003 SARS outbreak – Hong Kong’s COVID-19 death toll is four. But with their main form of defence (mass gatherings) neutralised, and the government drawing battle-lines for Legislative Council elections in September, protesters have been falling prey to targeted arrests and unprecedented changes to their legal system.

It is something that Antony Dapiran, a Hong Kong-based writer and lawyer, has called ‘lawfare’.

“What we’ve seen over the past few weeks is just the tip of the iceberg,” he said.

“They’re going to begin with the most prominent individuals, like the Democratic Party founder arrested last weekend. Then they’ll likely bring the weight of the law down on the roughly 6,000 arrested during the protests.”

This presents a bleak picture for Hong Kong democracy and for the protesters that Hannah saw running headlong at riot police.

“They were blocking off tear gas with their umbrellas and getting beaten until they were bloody,” she said.

“You could see from their frames that some of them were girls barely into their teens. They could have been at home being kids but they knew that if they didn’t fight they would lose everything. That’s why they were making petrol bombs in the street.”

Yet hope persists that Hong Kong’s future is still in its people’s hands.

“When Hong Kongers protest, we’re forced to put on masks,” Mic said. “So we tell each other that one day we’ll be able to go to the main government building, take them off and recognise each other for the first time. We’ll be able to turn to each other and say, ‘Hey, I know you!’”