When Naomi Bonafoux moved from Puerto Rico to London at 27 to get a Masters in physical theatre, she didn’t speak much English.

It was an opportunity to pick up the language and develop her career, but she never saw herself living in the UK long-term.

Now 12 years, a divorce and a daughter later, Naomi, 39, speaks English fluently.

She made a life in London, but is still dreaming of home in Puerto Rico.

She said: “I want to be by the beach, my mistake was marrying a British guy!”

Like other Puerto Ricans who swapped the tropics for a milder climate, Naomi always kept a careful eye on the issues affecting her home across the Atlantic.

She added: “It’s hard to detach, impossible sometimes, and I don’t think that feeling will ever go away.”

Puerto Rico, an unincorporated territory of the United States since 1903, has struggled economically for the past 20 years, which some believe is linked to the United States Congress decision to repeal a tax exemption on drug manufacturers in 2006.

The consequence was an exodus of foreign investment and pharmaceutical companies, which cost many Puerto Ricans their jobs.

In 2017, Puerto Rico received another blow with Hurricane Maria, which had a death toll of around 3000 people, according to George Washington University, though some believe figures could exceed 4000.

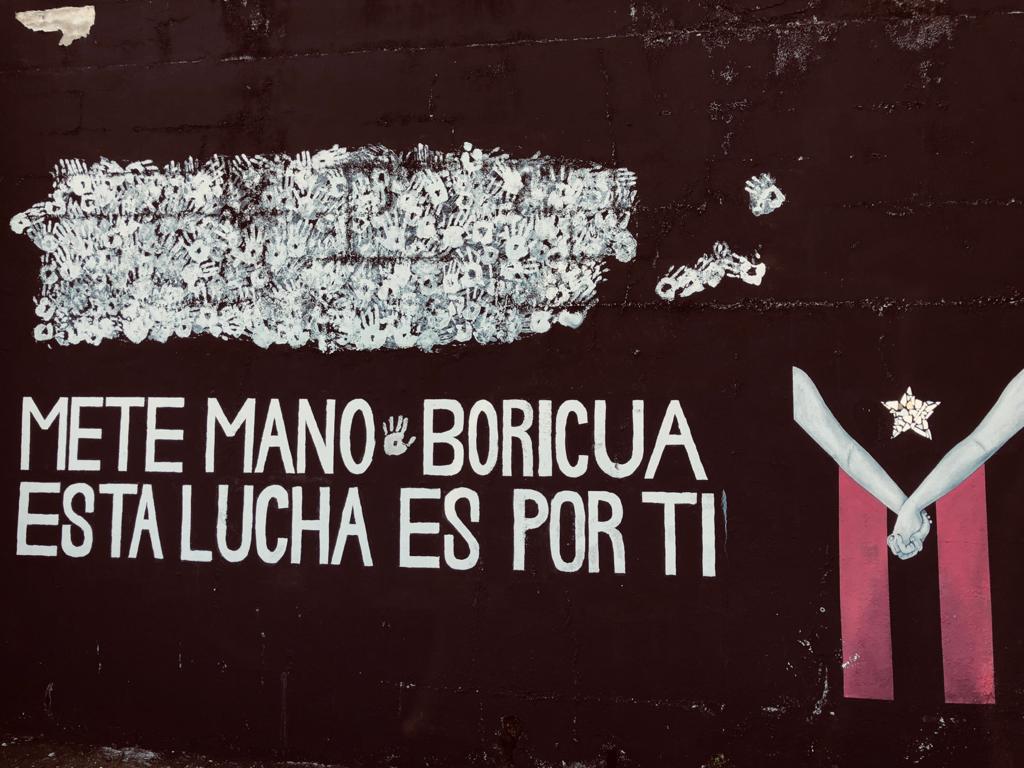

Last year Puerto Ricans globally took to the streets in mass protest, demanding the resignation of then mayor, Ricky Rosselló, after leaked WhatsApp messages revealed he took part in derogatory commentary and joked about hurricane victims.

But for Puerto Ricans in London, the grey cloud hanging over every problem back home is the political status, brought into the spotlight again at last month’s non-binding statehood referendum.

It was the sixth time citizens were asked whether Puerto Rico should be a US state or become politically independent.

52% voted in favour of statehood, but critics were quick to point out less than half of eligible voters, 1.2 out of an estimated 2.3 million, actually participated.

Nevertheless, the slim margin reflects a continuing identity crisis deeply ingrained among all Puerto Ricans, even those living 6,660km away in London.

Gabriel Mulero Clas, a 36-year-old international construction lawyer who left Puerto Rico ten years ago, said: “It affects the economy, it affects corruption and it affects the self-confidence of Puerto Ricans.

“When you’re outside of the entire ecosystem and you see how other people live around the world you realise, what’s wrong with independence?

“As far as I’m concerned, I’d be happy with either. That perspective comes from living not just outside of Puerto Rico, but outside of the United States.”

Maria Cristina Alvarez, a senior project manager at Amazon living in Battersea, disagreed.

Her experiences of living abroad shaped what she believes is a more realistic view on the island’s political status.

She said: “I don’t think it’s realistic for Puerto Rico to become independent. Our economy, our culture, whether people like it or not is very ingrained in American culture.

“Maybe I have this opinion because I came here as an immigrant and fully appreciate the benefit of being a US citizen and having freedom of movement. A lot of people in Puerto Rico take that for granted.”

Part of why Maria Cristina, 34, moved to New York and later London, after attending Georgetown University in Washington DC instead of going back home was because of an incident during her senior year of high school.

One of her friends was killed in the crossfire of a drug gang war.

She added: “The death of that girl was a big thing for me not going back. I wanted to be young and carefree.”

For Naomi, living in London has solidified her view that Puerto Rico is destined for independence.

Growing up in Guayanilla, a town in the south of the island, her dreams of seeing her home ‘free’ from colonial vestiges stemmed from her relationship with her uncle, Carlos Reyes, a former mayor and member of the independence party.

He became a parental figure in Naomi’s life at a young age, after her own father who fought in Vietnam, died of cancer linked to the chemicals in ‘Agent Orange’, a sacrifice she felt has never been acknowledged by the US Government.

She said: “We never got any support, any psychological help. He got nothing for being a veteran.”

“My uncles came to take care of us and he [Carlos Reyes] was one of them.

“He made sure that we had the ideas that we deserved to be free.”