Two years ago, I received a harrowing phone call from my father informing me that my cousin had taken her life following an excruciating lifelong battle with her mental health.

As he wept down the phone, all I could think about was the frantic messages I had received from my cousin a few weeks prior, sharing her fears about being diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD), also known as Emotionally Unstable Personality Disorder (EUPD).

Estimated to affect 1% of the UK population, researchers believe BPD develops from genetic and environmental factors, such as stressful or traumatic events in childhood, impacting how people think and feel about themselves and others, which presents long-term difficulties that challenge their ability to cope with everyday life.

There are conflicting opinions on whether receiving a diagnosis is beneficial or not, as the mental health charity Mind affirmed: “Some of us find it useful to have a diagnosis because we feel it explains and helps us to understand our difficulties, or gives us a sense of relief and validation. It may also be helpful for accessing treatment or support. Or to put a name to our experiences and connect with others.

“On the other hand, some of us don’t find our diagnosis helpful. We may find it stigmatising and feel it suggests that there’s something wrong with who we are. Then there are also some of us who disagree entirely with the current system of diagnosing personality disorders and prefer not to describe our experiences as medical problems. We may see them more as a response to trauma, difficult life events or problems in our society.”

I could not help but wonder whether the diagnosis and stigma entangled with personality disorders had simply felt too overwhelming for my cousin.

Perhaps if we were better informed as a society about mental health disorders, accessing treatments and success stories, she would still be here today.

In the late 1980s, American psychologist Dr. Marsha Linehan devised Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT), determined to redefine the treatment landscape for patients also grappling with BPD.

Drawing on her own traumatic experiences as a blueprint for change, she developed the cognitive-behavioural treatment for individuals who experience emotions intensely to comprehend and accept their difficult feelings, learn skills to manage them and implement positive life changes.

The ‘dialectical’ element differentiates the treatment from other talking therapies by emphasising that whilst two things can be opposing, they are not mutually exclusive – for example, patients can embrace accepting themselves and simultaneously work at changing their behaviour.

Since 2019, NHS Mental Health Trusts have been the sole provider of free DBT programmes in England, which the public can access via GP referrals.

The NHS DBT programmes, which typically take a year to complete, incorporate a weekly one-to-one therapy session, telephone coaching, and a weekly group session focused on the core skills modules: distress tolerance, emotional regulation, interpersonal effectiveness and mindfulness.

After spending over ten years in mental health nursing, psychotherapist Emma Pott decided to train as a DBT practitioner and has been working for the South West London and St. George’s Mental Health NHS Trust for the last six years.

Through her experience and field research, Pott maintains that it does not matter how highly qualified a therapist is or what modality of therapy is offered, the most important component to achieving results comes down to the quality of the therapeutic relationship.

She expressed: “Most people who come to DBT have had traumatic attachments, so the therapeutic relationship is an opportunity to learn what a different attachment looks like. It’s about getting the balance right, and not being too formal.

“I would never ask a client: ‘How does that make you feel?’ I hate that so much – for me, that’s not therapy! It’s also about having a bit of a laugh and calling things out because that’s representative of what a real relationship is like.”

Pott believes that growing up with the emotional complexities of having an alcoholic parent and being a former DBT patient herself has been pivotal to her establishing successful therapeutic relationships that are rooted in empathy, connection and unconditional regard.

She said: “I haven’t met a therapist who hasn’t gone into mental health, who hasn’t had their difficulties. And I think it’s a really important factor when you’re working with the nature of the difficulties DBT patients experience. It doesn’t mean you get it, but it means that you can empathise more because you’ve been on that side of the fence.”

The South West London and St. George’s Mental Health NHS Trust (SWLSTG MHNT) oversees 17 local teams, which have facilitated DBT services for 1,199 individuals over the past five years.

In 2022, 286 people registered for DBT services, making it the year with the highest enrollment figure – 12% more than in 2023 and 44% more than in 2024.

Chief finance and performance officer for SWLSTG MHNT, Philip Murray, disclosed that it costs them around £22,339 to deliver a stand-alone DBT skills group for six months, delivered by an 8a and band 6 member of staff, which roughly works out at £2,567 per patient, if 10 patients are part of that group.

Murray noted that this estimate does not include the full costs of DBT per patient, and fees can vary depending on the seniority of the staff member delivering the course.

Across all boroughs, there were striking trends in the data regarding the gender and age of people enrolling for DBT services.

Between 2019 and 2024, 85% of those who registered were women, which Pott said is indicative of biological and social gender differences, which make women more likely to receive a BPD diagnosis than men.

She said: “When women are experiencing distress, they are more likely to take on that emotion internally, which is why they are statistically more likely to self-harm.

“It is more socially acceptable for men to show outward signs of aggression, such as punching a wall, which is why these unstable emotions are much easier to identify in women.”

Pott continued: “Women tend to use the right side of their brain more – the creative side – meaning they are typically more social and willing to talk with their friends about their difficulties. Within our society, there are several mental health campaigns encouraging men to talk about their feelings, deriving from high suicide rates for men.”

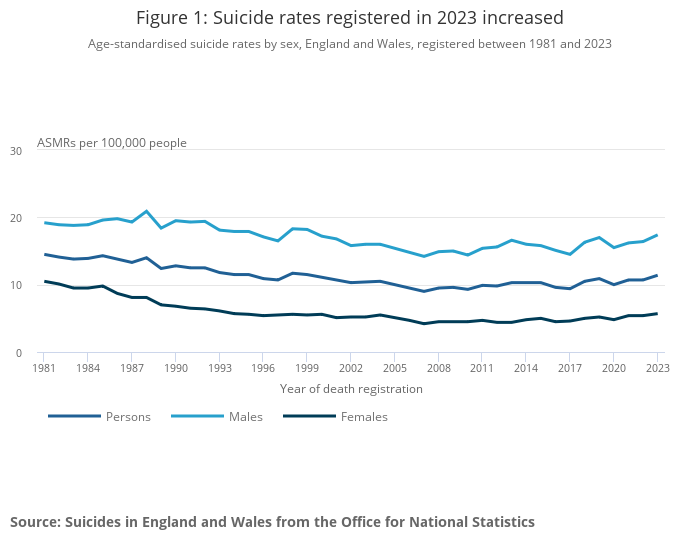

Data shared by the Office of National Statistics on suicide in England and Wales between 2011 and 2021, established that rates were much higher in men compared with women across all ages, and men between 40 and 50 years old had the highest rates overall.

The data for DBT service enrollment highlights a greater issue we are attempting to confront in our society about how we can encourage and support men in accessing the mental health help they need.

Another notable trend in the data concerns the age of those accessing DBT services – the 18 to 24-year-old category consistently ranked highest year on year, accounting for 43% of the total, and the 25 to 34-year-old age group followed behind with 34%.

Providing the reasoning behind this age group having the leading figure, Pott attested: “Firstly, that is the age range where these difficulties are most prominent. If we think about statistics relating to gender and age, young women are more likely to self-harm, take overdoses, rock up at A&E and seek treatment. Secondly, I think social media has helped with people normalising mental health difficulties, particularly trauma.”

Pott also pointed to neuroplasticity in the brain and creative adaptation to explain why the data for those over 35 is considerably lower.

She said: “Evidence shows creative adaptation happens by the time people reach 40, not because they are not suffering or finding it difficult to manage their relationships and emotions. Instead, they have got so used to their issues by then, they just crack on with things.”

With these age trends in mind, we can fathom why Kingston had the highest number of 366 enrollments (31% of the total) compared to other areas, given the four university campuses that span the borough.

Pott added: “Especially around this time of year, we see a lot of transfers, particularly in North Kingston, because lots of young people are starting university and need to access DBT services more local to them.”

Savanah Ridpath is a 23-year-old residential children’s support worker, who was studying art at Kingston University when she signed herself up for DBT services in 2019.

Looking back on the issues that prompted her to pursue help, Ridpath shared: “I was grieving the loss of my parents from when I was younger and I was not sure how to manage my feelings about that. I was also facing a lot of hardships in my friendships. I was being quite destructive – engaging in self-harm, sexualised behaviour, drug use and alcohol. I was at a point where the people around me were starting to get hurt mentally.”

Growing up in care, Ridpath had accessed other forms of therapy such as CBT and counselling but found DBT to be considerably better owing to the constant support she received from her therapist through telephone coaching outside of the weekly in-house sessions.

Of all the course elements, she found the weekly skills group most engaging and an opportunity to connect with others who shared similar experiences and issues, making her feel less alone.

Nonetheless, working in a group with other people who feel emotions intensely did not come without its challenges, as Ridpath recalled: “The most difficult aspect was when other people got triggered in the group. This was a bit like a domino effect, we could easily set each other off. If someone was having a very bad day, everyone in the room felt it, which was hard at times. But it also brought us closer together, learning to support one another.”

Since completing the course, Ridpath is proud of her newfound ability to slow down when she is feeling emotionally heightened or cascading into a negative headspace by asking herself questions such as: “Why am I feeling like this? And what can I do to feel better?”

She said: “It can be hard to remember all the skills, but it makes you stop and think about it first, not just go all guns blazing and be impulsive, which has been really helpful. DBT helped me to identify my feelings, understand where they are coming from and consider my actions.”

Desperate to change for her children, 49-year-old Susan Osborne embarked on her journey with Kingston DBT Service in December 2022 after acquiring a diagnosis of BPD.

Throughout her life, she had battled with an eating disorder, mood swings, suicidal thoughts, and alcohol reliance, all of which led to her previously receiving diagnoses and treatment for Anorexia and Bipolar Disorder.

In the mental health field, psychotherapist Pott explained that it is notoriously tricky to diagnose BPD, which is why it is not uncommon to hear about misdiagnosis experiences from those involved in DBT services.

Reflecting on this experience, Osborne expressed: “Having these diagnoses did not help me to deal with the real problems, my triggers, and where my difficulties stemmed from. They just gave me labels, which at first seemed helpful but were not always accurate, especially in the case of the Bipolar.”

Osborne contended that the DBT programme was the most transformative and practical of all the therapy courses she has participated in and considered the group activities as crucial to her becoming more aware of herself, her behaviours and others.

She said: “I think everyone should do it, whether they have mental health issues or not. The important tools I learnt will be passed on to my children. The only difficulty is keeping up the skills we learnt in a clinical setting and applying them to the outside world. It’s easy to remember what to do, but the process of doing it can be hard. Not falling back into old patterns can be a real challenge!”

These moving stories of success are exemplary of the importance of investing more in local NHS Mental Health Trusts to continue to provide free therapy services to support those toiling with suicidal thoughts.

As I was interviewing these inspirational mental health workers and former DBT participants, it was impossible not to think of my cousin and ponder if she had obtained the correct diagnosis and treatment earlier, would things have turned out differently?

In March last year, the Office for National Statistics published that there were 6,069 registered suicides in England and Wales in 2023, an increase from the previous year and a record high since 1999.

We need to be having these conversations more than ever before to educate the public on mental health disorders, accessible treatments and how they can support those closest to them to break the stigma and save lives.

Despite this national epidemic, suicide is still a taboo topic in our society that we shy away from because it makes us feel “uncomfortable”.

I know I would choose a thousand uncomfortable conversations with my cousin any day over living with the discomfort that I will never hear her voice again or that her seat at the family table will remain empty.

If you or someone you know are experiencing suicidal thoughts, you can reach out to the Samaritans 24 hours a day and for free via the link here – you do not have to suffer in silence.

Feature image courtesy of Canva’s stock image library, with thanks