South West Londoner interviews Icelandic band Hatari to discuss their documentary ‘A Song Called Hate’, which offers glimpses behind the glitzy cosmetic exterior of the 2019 Eurovision Song Contest into Israel’s troubled divisions through the eyes of both Palestinian and Israeli artists.

It was the night of the Eurovision Grand Finals 2019, and half of the public vote had already been announced.

Frontrunners waited anxiously as some countries clambered up the leaderboard, while unpopular entries like the UK and Germany sank lower and lower.

Then, it was time for Iceland’s score.

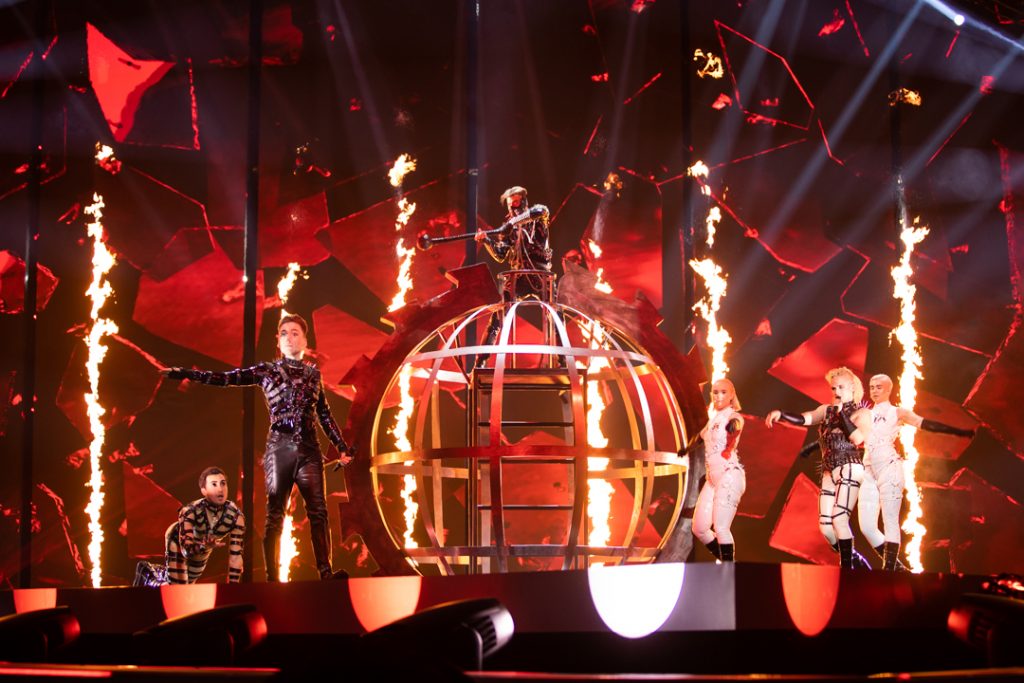

When the camera cut to the Nordic country’s latex-clad contestants, what happened next was a brief but dramatic moment which left its mark on the competition’s long history.

Captured on live TV, any viewer could easily spot the colours red, black, white and green.

Hatari, which has been described as an anti-capitalist, BDSM, techno-dystopian performance art collective, chose this moment to hold up Palestinian banners, right in the centre of Tel Aviv.

When the crowd saw the banners, there was an uproar that could be heard clearly through the microphones, as their political statement was met with outrage.

“It’s such a small gesture, holding a nation’s banner,” said Hatari co-founder, Klemens Hannigan.

“Other contestants were holding banners for their own countries and other countries, but the disproportionate reaction we got to this small gesture – over 7000 people in the audience screaming at us and being verbally attacked – is crazy and really helps put what’s going on into perspective.”

An Embassy of the State of Israel source told South West Londoner: “There is a difference between art and politically attacking the host (Israel) of the contest unilaterally, by ignoring the fact that the song contest is apolitical as stated by the official rules and the guidelines which bans the use of actions that are politicised.

“The contest is a beautiful way to artistically connect people and countries. Hatari did exactly the opposite.”

Differing viewpoints aside, what audiences didn’t know was that this moment of rebellion had been a long time coming for Hatari.

Their new documentary ‘A Song Called Hate’, which premiered one week ago today at London’s BFI-backed Doc’n Roll Film Festival, explores the band’s journey from a grassroots anti-capitalist band to one of the most controversial acts ever to perform in Eurovision.

The origins of Hatari

In 2015, Klemens and cousin Matthías Haraldsson founded a daring new techno performance group in their hometown of Reykjavik.

The musicians have always stated in deadpan fashion that their goal is to destroy capitalism from its roots, so the band has always been political and subversive, although they’ve kept it fairly tongue-in-cheek in the past.

Once, when Hatari were invited to play a gig at the University of Iceland, they were reminded by the organisers to thank the Icelandic bank Landsbankinn, who were funding the event.

“We were like: wait, what?” Matthías recalled. “We’re an anti-capitalist punk band and we’re supposed to thank the Bank of Iceland?”

In the end, the band came up with the creative solution to photoshop a picture of their drummer, Einar Stefánsson, in a gimp mask signing an agreement with a member of Landsbankinn.

They changed the text below it to show that they were now collaborating together on the destruction of capitalism.

So how did this droll duo and the rest of their ensemble end up on the Eurovision stage?

In their documentary, the celebrated Icelandic artist Ragnar Kjartansson suggested: “Most art projects are basically jokes gone too far, and I think that’s how this must have started.”

When the band’s entry into Eurovision was successful, however, it forced them to consider seriously how they wanted to use their new-found platform.

Iceland, along with Sweden and Malta, is one of only three Western European countries to recognise Palestine as a state, according to the list maintained by The Permanent Observer Mission of The State of Palestine to the United Nations.

Klemens said: “When we decided to participate in Eurovision 2019, it was a big step filled with contradictions, as there was a huge movement here in Iceland to boycott the competition that year because it was located in Tel Aviv.

“Once our national broadcaster decided to go through with it, we felt that if there should be an Icelandic participant, then that participant should at least try to show solidarity with Palestine or to use this unique platform to raise awareness.”

Making the documentary

Alongside their stint in Eurovision, Hatari wanted to film a documentary to capture their journey through the country to meet with different artists.

They interviewed artists from both communities, including Palestinian musician Bashar Murad and fashion designer Reem Kawasmi, as well as Israeli contemporary artist Itay Zalait and film director Nadav Lapid.

By providing greater context for Hatari’s actions, ‘A Song Called Hate’ is able to unpack the thought process behind the many controversial decisions they made throughout the competition.

Klemens said: “I feel the documentary plays a huge part in keeping the narrative alive, because the actual moment of us waving the Palestinian banner is such a chaotic glimpse, a second that disappears into nothing, unless you have a way to keep the story going.”

‘A Song Called Hate’ first aired in Iceland over a month ago and has already been nominated by the Icelandic Film and Television awards for Best Documentary and Best Musical Score.

Anna Hildur, the documentary’s director said: “I want people to come on this journey with us and feel it. Hopefully, it is inspiring enough for people to engage and want to strive for freedom of expression and human rights.”

The documentary also explores the conflicting pressures the band felt from different parties, including the Palestinian community, Eurovision organisers and their home country.

“Sitting here in Reykjavik, you maybe have a naïve idea of how things might play out and every day from there it was just about navigating those questions,” Matthías explained.

One key outcome of Hatari’s visit was the collaborative partnership they formed with Bashar, who went on to record the single ‘Klefi/Samed (صامد)’ (or ‘Chamber/Steadfast’) with the band and later performed on stage with them in Iceland.

In the documentary, Bashar described how, in a bid to get Palestine into the competition, his mother had once travelled to Finland to hold the Palestinian flag at a Eurovision event, which led to it being banned from all future events.

Recalling the moment Hatari reached out to him, he told South West Londoner: “I had recently been talking about the hypocrisy of Eurovision, when along came this opportunity where I felt like I could really do something, maybe even burst the Eurovision bubble.

“After our collaboration, it was the first time where I felt like I could still break taboos in my community, still sing in Arabic, but also with a message that is effective on a global scale.”

On Bashar’s recommendation, Hatari visited the cities of Hebron and Bethlehem to see the conditions of people living there for themselves.

Matthías described the sobering juxtaposition of this visit with the Eurovision experience that followed immediately after.

He said: “When you’ve been to Hebron and Bethlehem where the occupation is so clearly felt, Eurovision seems so alien.

“We had this feeling of being the elephant in the room; all the time having this picture in the back of our minds of checkpoints, soldiers and occupation forces just a short drive away from where we were answering questions about our outfits.”

“It really felt like we were in the Hunger Games opening ceremony,” Klemens added.

On the evening of the Grand Finals, Iceland received a combined score of 232, landing them in 10th place overall.

There was a notable disparity between the public vote, with every country save North Macedonia awarding enough points to place them sixth, while in the jury vote only nine out of 35 countries gave them any points at all.

How might these scores have differed if they had raised their flags before voting had finished? Would they have been excluded from the competition altogether?

Judging by the footage of their strained conversations with Eurovision executive supervisor Jon Ola Sand, they were already on very thin ice.

Backlash

At the climax of the documentary, after Hatari’s Palestinian banners are confiscated, there is a genuine feeling of fear and uncertainty, as they face hostility from those they have offended.

Matthías reflected with hindsight that, while they received jeers and threatening messages, they were not in real physical danger.

He explained: “We were aware of our privileges as foreign representatives of a country. It’s almost like diplomatic immunity but it’s pop competition immunity.”

Judging by the crowd’s reaction, however, it would appear that many Israelis were seriously upset and offended by Hatari’s conduct in the competition that their country had hosted.

One Israeli citizen, who wished to remain anonymous, told South West Londoner: “Freedom of speech is important, but you still have to be respectful.

“Eurovision is a competition with a very formal set of rules and Israel was the host country, so I think it was disrespectful to take advantage of a stage that someone gave them.

“In life things are rarely black and white and the truth often lies somewhere in the middle.

“It’s a complicated conflict, and I’m not sure whether Hatari took the time to learn the subject and took the time to understand the position of both parties.”

Ultimately, a lot of criticism appears to be directed towards Hatari’s promotion of their political beliefs in a competition that claims to be purely apolitical.

While this issue is up for debate, it also raises a larger question: what is the role of artists and musicians when it comes to politics?

Politics in pop music

In the age of social media, when artists’ off-stage platforms are becoming increasingly important, the issue of using those platforms responsibly has never been more relevant.

In ‘A Song Called Hate’, Ragnar Kjartansson discusses the social responsibility of artists.

He said: “We live in interesting times where there’s this constant demand that art should be responsible.

“But art always finds a way to swim through being responsible, and this irresponsibility is the responsibility of the artist.”

Freedom of expression is a central ideal of Western democracy, and so in this way, artists are able to argue that they should not forgo their rights to free speech for fear of political censorship.

Also in the documentary, Icelandic Prime Minister Katrín Jakobsdóttir said: “I don’t think I can place any responsibility on artists to do this or that.

“But I think it’s the responsibility of us, as a society, to give them that freedom to fight for a cause.”

Hatari weren’t the only musicians to champion a particular political cause in 2019.

That July, the 1975 released a self-titled track featuring a monologue from environmental campaigner Greta Thunberg, and one month later, local Hong Kong artist Thomas Dgx Yhl released a song called ‘Glory to Hong Kong’ in protest of its controversial extradition bill.

Music and politics have long been intertwined, from the early protest songs of Woodie Guthrie to the angry anti-establishment sentiments of the Sex Pistols.

But what do these artists hope to achieve?

Klemens said: “One of the roles of art is to ask questions and to make people ask themselves questions.”

Matthías added: “It’s a common misunderstanding that the critics are the negative ones. If you are criticising a situation, you are usually doing it out of the hope things can get better and that goes for our music.

“Because, if you were completely hopeless you wouldn’t be doing anything.”

Ultimately, Hatari’s Eurovision song warned of a dystopian future where Europe will collapse and where unless we change the way we treat one another, hatred will prevail.

Were they right?

The documentary in today’s context

Those involved in the making of ‘A Song Called Hate’ noted the timeliness of its release date, given the recent violence that erupted between Palestine and Israel exactly two years after Hatari took to the stage in Tel Aviv.

Anna said: “Sadly, the film is even more relevant now than when we were making it, but if it helps to tell the story of the struggle Palestinian people are experiencing on a daily basis, it was worth doing.”

Matthías added: “I am a lot more emotionally attached to Palestine now.

“It was a place that I heard about on the news, but now when I read about bombings or assaults on protestors, or watch Bashar’s stories on Instagram, it feels much closer to home.”

Bashar pointed out that the 2021 Eurovision finals followed just one day after Israeli and Palestinian militants agreed to a ceasefire after 11 days of conflict, which cost at least 243 lives in Gaza and 12 in Israel.

He said: “It is jarring, given what is happening in the country right now, that they then just have this competition bubble where they act like everything is good.

“I was waiting for someone to raise the Palestinian flag again, but it didn’t happen this year.”

Regardless of how you feel about Hatari and their politics, ‘A Song Called Hate’ does offer a uniquely artistic perspective on Israel and Palestine in a time where tensions between the two countries are extremely fraught.

So, will hatred prevail? That remains to be seen. But as long as artists have the freedom to scream such questions from the tops of their lungs, the world cannot ignore them forever.

‘A Song Called Hate’ premiered last Wednesday 16th June at the Rio Cinema in Dalston and will hopefully be making its way to streaming platforms later this year.

Featured image credit: KAN