Deaths from drug poisoning in England and Wales have reached their highest level since data collection began, according to new analysis from the Office of National Statistics.

The number of all drug related poisonings has more than doubled in that time frame, rising from 2,178 in 1993 to 4,907 in the most recent 2022 study of death certifications.

A death is ruled a drug poisoning when it occurs as the result of exposure to prescription, illicit or over-the-counter drugs.

This also includes deaths from drugs misuse, when happen when a drug is not used along legal or medical guideline.

The age-standardised mortality rate from deaths due to drug poisoning, which adjusts the raw death figures for population size and age distribution, has risen every year since 2012.

If these trends are to be reversed, the natural next step is to identify the factors driving increased drug use.

This might be easier said than done, as it is likely that several overlapping factors are all in-play at once, making it more difficult to disentangle them.

On the possible explanations, author of the original ONS statistical bulletin Paul Breen said: “There’s a number of things which it could be.

“The people that we’re seeing the highest rates of death in are getting older.

“So it could be a case that as they age they are less able to survive the effects of the drugs.

“It could also be the cumulative effect of many years of drug taking.”

If age is the most important factor the rise in deaths, it is hoped that mortality rates could fall as older generations are replaced by cohorts less likely to use drugs.

Were this the case, then drug deaths may reach a natural peak in the short-to-medium term, although this would require keeping drug use from penetrating into younger generations.

Regarding the origins of Generation X’s struggles with substance use, Breen said: “People born from 1965 to 1985 have always had the highest death rates.

“They’ve had the highest rates since they were in their 20s and now they’re in their 50s.

“Again it’s difficult to say why, but it tends to be higher in more deprived areas, and these are people who grew up around the time that they became deprived, in post industrial areas and sea-side towns destroyed by international flights.”

Trouble on the Horizon

The ‘natural peak’ hypothesis rests on the assumption that younger generations will not emulate the habits of their predecessors.

Unfortunately, there are worrying signs that this might not be the case.

Deaths rates in these groups, while not as high as Gen X, have also risen across the board.

One potential reason for this is a concerning movement among drug users towards using multiple substances at once, also known as poly-drug use.

Most commonly, fatal effects result from a combination of prescription anti-anxiety medications, such as benzodiazepines or gabapentinoids, and opiates.

The average number of drugs mentioned on a death certificate has risen from 1.4-1.5 between 1993-2011, to two drugs per death in 2022.

While it may seem insignificant, the presence of even a single additional substance can raise the associated risks substantially.

Zooming in

In the capital, the picture is slightly less clear, as the total number of drug-poisoning deaths peaked in London at 555 in 1998.

However, there are still reasons to worry.

Nearly two decades of steady decline ended in 2012, after which deaths from a number of substances have climbed back into the range of their mid-90s peaks.

The burdens of drug-use and its associated harms are not evenly distributed between London’s boroughs.

Age-standardised mortality rates are highest in Hammersmith and Fulham, where 12.1 people per 100,000 population died from drug-related poisonings in 2022.

Conversely, the lowest rate is to be found in Barnet at only 1.6, while Harrow and Merton are only marginally higher at 1.7 per 100,000 people.

Solving a Silent Crisis

Given the scale of the issue, it seems that any successful intervention would have to be coordinated from the very highest levels of government.

Yet Dr Mohammed Al-Saidi, London clinical lead for addiction charity Turning Point, says there seems to be a lack of appetite from the general public and their representatives to make meaningful changes.

He said: “Politicians need to put it first on the agenda, how to protect the public from harm.

“But with so much complexity in the world that they don’t see this as a major problem, which is very sad really.

“We cannot force politicians to think, but we can make enough noise to get them to do something because we cannot continue doing this.”

Beyond using education to overcome public apathy, there is a growing push for more concrete policy changes in this field.

A July 2023 report from the Home Office Affairs Committee found that the government’s existing 10-Year Drugs Strategy is unlikely to have a meaningful impact in reducing drug deaths.

Instead, it argued that existing drug classifications were outdated and in need of reform so that the controlled substances are prohibited to a degree more in line with their actual societal harm.

As well as this, it called for a move away from criminal sanctions for low level offending and towards diversionary measures, coupled with a range of harm reduction provisions aimed at protecting public health.

One example of this would be supervised consumption facilities and drug checking services.

On the need for a change in attitude towards drug policy, Home Affairs Committee chair, Dame Diana Johnson, said: “Fundamentally, we need to have the right interventions in place to help people break free from the terrible cycles of addiction and criminality that drug addiction can cause.

“Simply attempting to remove drugs from people’s lives hasn’t worked.”

If you struggling with substance abuse, in person support can be found on the Turning Point website.

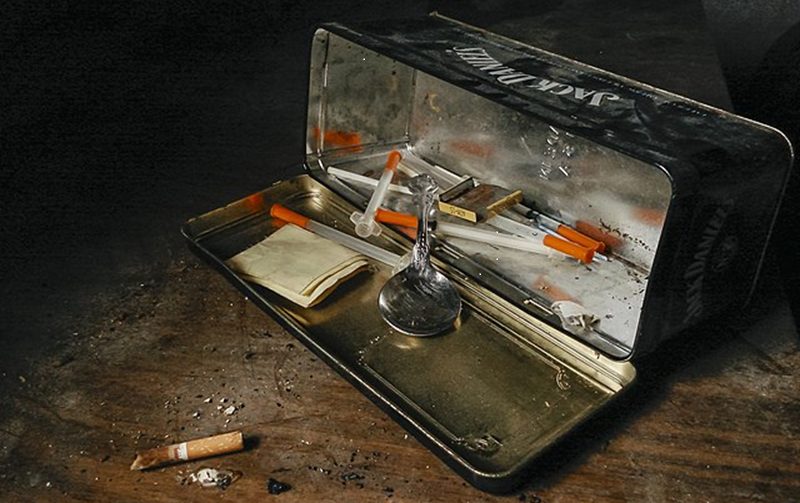

Feature image courtesy of Matthew T Rader under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

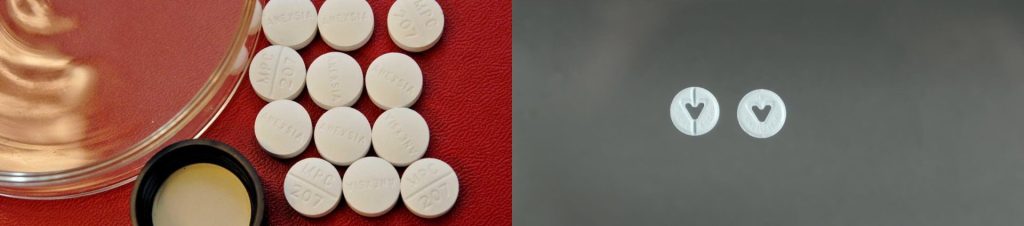

Inset image courtesy of the Drugs Enforcement Agency