Groundwater reserves in south London may run low as the capital is projected to face severe water stress by 2050, a researcher said.

Barnaby Dobson, a hydrologist at Imperial College London, voiced concern that boreholes and aquifers may be first to feel the impact as water demand increases while supply is projected to fall.

Around 25% of the capital’s water supply comes from groundwater reserves located primarily in the south London while the remaining is gained from the rivers Thames, 50%, and Lee, 25%.

Dobson said: “If we talk about literally running out of water, it is groundwater that is the more concerning one because while we have a lot of models telling us how boreholes and aquifers may behave, we have not really tested them in extreme scenarios.”

The lack of data on how groundwater supply could behave during droughts makes it difficult to prepare for extreme weather scenarios, according to Dobson.

He continued: “We don’t really understand, when it comes push to shove, what will happen to groundwater supply during a drought.”

A drought occurs during an extended period of unusually dry weather and in the UK it is specifically defined as a period of at least 15 consecutive days in which rainfall does not exceed 0.2 millimetres.

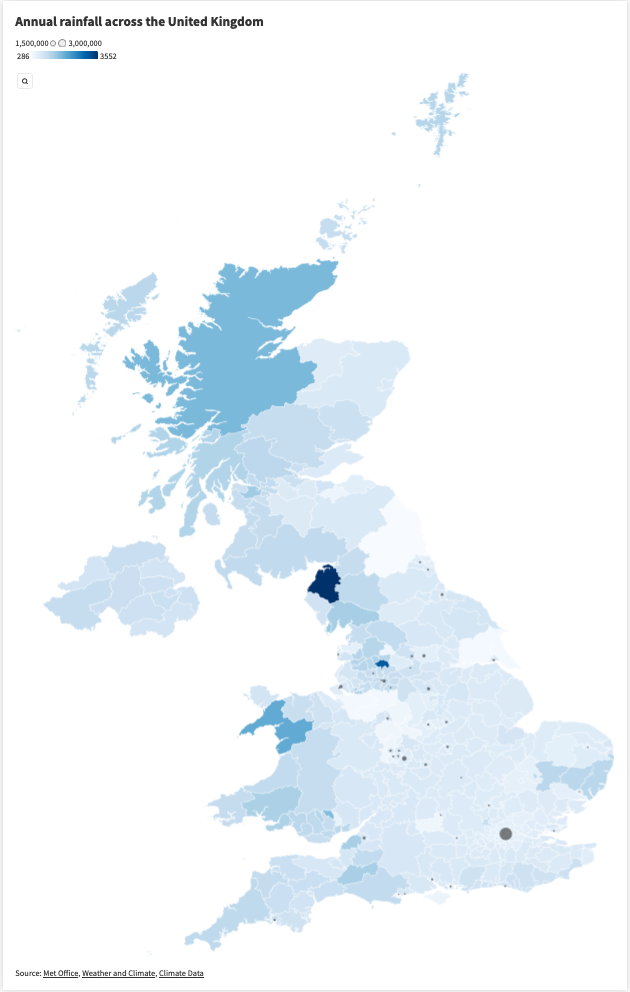

London receives less rain annually than New York or Sydney and the Environment Agency already classifies the capital as being in water stress, meaning demand for water could outstrip supply.

However, Dobson warned that population growth may be the more worrying cause of water stress as London is projected to reach 13.4 million inhabitants by 2050 which could result in demand for water outstripping supply by 20% by 2040.

Taking all factors together, a recent report by Christian Aid estimated that London could be running out of water within 25 years.

Darío Soto-Abril, CEO of Global Water Partnership, works with a global action network aiming to ensure water security around the world.

According to him, the most important aspect for countries will be to increase coordination between various interest groups and develop a comprehensive water strategy.

Soto-Abril said: “Integrated water resource management is the idea that if you sit down with the different sectors such as agriculture, industries, government and society you will have better policies allowing you to plan and prevent ahead of time.”

In 2020 the Environment Agency set out a national framework for water resources, detailing the scale of action needed to maintain water supplies.

An Environment Agency spokesperson said: “Five planning groups made up of water companies are developing plans to secure resilient water supply for England to 2050 and beyond.”

Acknowledging the particular water stress in south east England, Thames Water will also publish a draft plan in November on their own strategies to ensure water security in the area.

The draft plan will set out proposals to half the amount of water lost through leaks in water pipes by 2050, to increase installation of smart water meters and reduce overall consumption, and develop new sources of water through recycling schemes, regional transfers, and new reservoirs.

Dobson from Imperial College said: “Solutions that aren’t talked about much that I would like to see more of would be rainwater harvesting which people could use for gardening.

“It’s not going to solve the world because it’s not going to fix the biggest droughts but it does buy a bit more time.”

Additionally, according to Dobson, shortages in south London groundwater reserves would not affect the local population but London as a whole as water in the capital is supplied through an integrated grid.

The most likely impact on consumers in the near future would be a hosepipe ban, Dobson estimated.

He said: “A hosepipe ban is not the same as literally running out of water, rather hosepipe bans and similar things that Thames Water can do to increase water supply and decrease water demand as interventions before we reach that point of Day Zero where there is literally no water left.”