NHS Blood and Transplant (NHSBT) is launching its first national campaign calling for more people to donate plasma, which can be used to make medicines and help those with immune conditions.

NHSBT, hoping to more than double the number of plasma donors in London by September, has set up three donation centres in the city, two of which are located in Croydon and Twickenham.

The shortage of plasma donors

In 1998, there was a ban placed on using plasma from UK-based donors because of the risk of spreading BSE (also known as Mad Cow Disease) – which had a strong presence in the country at the time.

In April of this year, after a gap of more than 20 years, plasma donation was reintroduced following the MHRA‘s assurance that it could be carried out safely again.

However, due to the long hiatus, it’s hardly surprising that so few people know about it. According to an NHSBT survey, only 23% of the public know what plasma is, and this lack of awareness is contributing to the shortfall in donations.

Currently, there are:

- 638 active plasma donors in Croydon, compared to the 1,050 needed.

- 1,069 active donors in Twickenham, compared to the 1,400 needed.

- 1,035 active donors in Stratford, compared to the 1,400 needed.

So what exactly is plasma?

While most of us are familiar with blood donations, fewer people know about plasma.

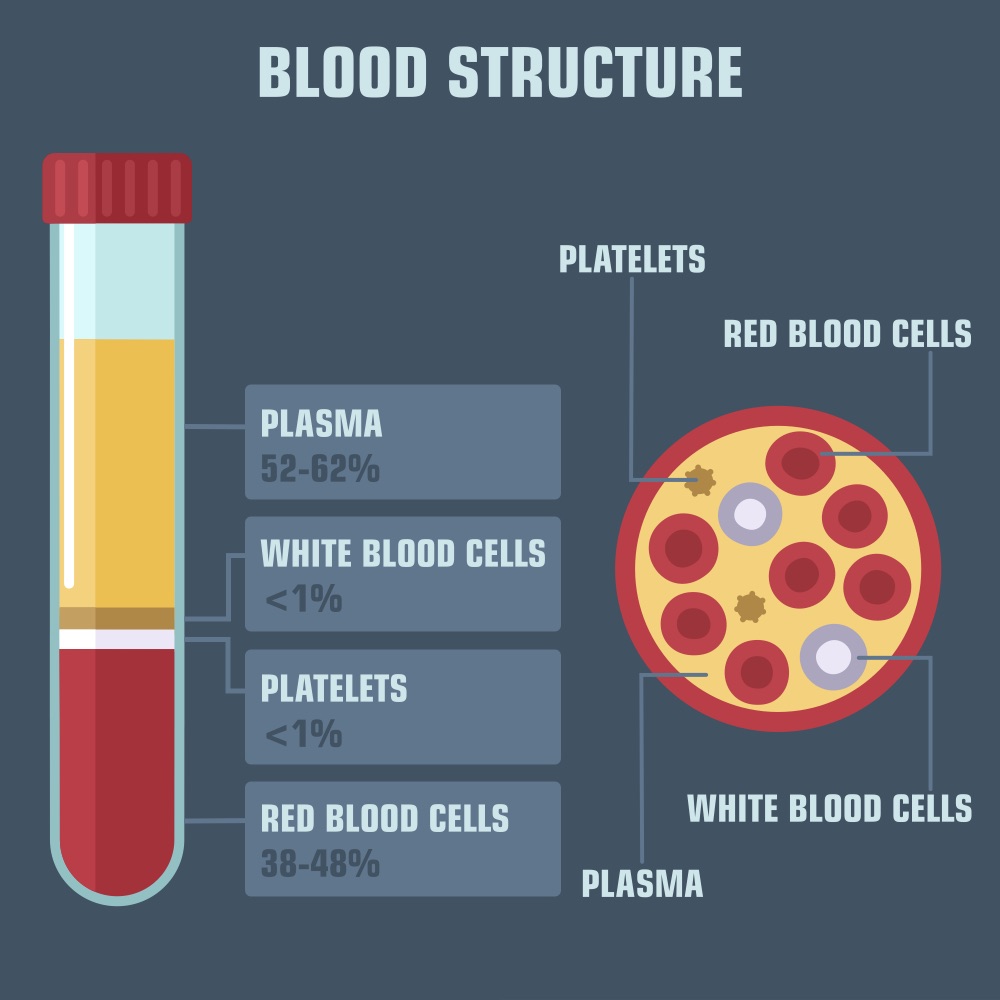

Plasma is a fluid contained on our blood, making up more than half (55%) of it, which carries platelets as well as both red and white blood cells around our bodies.

When someone donates plasma, it’s used to make medicines called immunoglobulins that are then given to help people with immune disorders. Around 17,000 people a year receive these medicines.

The need for UK-based donors

SWL spoke to Dr Aisling Carr, neurologist and clinical lead for the neuromuscular immunoglobulin service at the National Hospital of Neurology and Neurosurgery, in order to find out more about the plasma shortage and why donations are so desperately needed.

Dr Carr, 42, from Belfast explained that due to the donation bans in the UK, the plasma product they have been using for the last two decades has had to be imported from other European countries and the United States.

However, she explained that every now and again, global pandemics included, there can be shortages or difficulty with supply with demand.

“Anything could affect imports, any global factor at all be it financial, be it health-related, one country falling out with another, and all of these things affect how easy or difficult it is to import products,” she said.

“Whenever we’re dealing with products that have major impact on people’s life and their lifestyle, then we must do everything we can to improve the stability of the availability of these products.

“If we have a strong UK-based donor system, all of those potential difficulties of supply and demand from other countries will hopefully be less challenging to deal with.”

Dr Carr also highlighted the added benefit of a reduced environmental impact when using essential plasma-based medicines that are produced in the UK rather than shipped from different corners of the world.

How does plasma donation work?

Dr Carr explained that the process of donating plasma is almost identical to that of donating blood.

She said: “In blood donations, we take the red cells, which are what people need if they’ve had severe bleeding after an operation, for example. But there’s an awful lot more in our veins and blood vessels that play very active roles in protecting our bodies from infection.

“So in plasma donations, we take some of the volume from your bloodstream, but give you back your red cells so you don’t feel the same sort of tiredness that you might experience after a blood donation, and use only the plasma.

“That plasma is processed to make sure it’s safe and stable and then we use the immunoglobulins, which are antibodies that are dissolved in our plasma, to make immunoglobulin infusions.”

Dr Carr added that each batch of immunoglobulin infusion is made from the plasma of around 10,000 donors, providing a very broad mix of antibodies that can then be given to the people who need it.

Who does plasma help?

Immunoglobulin is generally given to two sets of people.

The first is made up of those who are immune deficient, such as people who are born with very low levels of antibodies to being with, or people who after blood cancer or even cancer treatment are no longer able to create their own antibodies.

“If these people don’t receive replacement antibodies via plasma, then they can’t fight infection, will get very sick from being exposed to simple bugs, and will die,” said Dr Carr.

“But with small infusions regularly of other people’s plasma, they can fight infections almost normally.”

The other group is made up of people with autoimmune diseases. In these cases, the immune system is overactive and attacks the body’s own tissue, causing damage.

Dr Carr explained: “As a neurologist, I deal mostly with immune conditions that attack the nerves or the muscles in the arms and the legs. The conditions I use the plasma products, the immunoglobulin, for are things like VAP and Guillain-Barré syndrome which can cause people to be very weak and unable to move or walk.

“So for people with certain conditions, these infusions are life saving.”

“It’s helped me live a fairly normal life”

SWL also spoke to Lucy Melsom-Morgan, 24, from Finsbury Park, who has a rare immunodeficiency disease called Hyper IgE (also known as Job Syndrome).

Melsom-Morgan has been struggling with Hyper IgE since she was six months old, though the condition wasn’t formally diagnosed until she was 19.

Due to the condition, she is more susceptible to chest infections, skin infections, and other internal infections like abscesses. To manage the condition, she receives immunoglobulin infusions once a month.

She said: “I don’t really go out anymore, but pre-covid especially I’d be more likely to get a cold in the run up to receiving my next infusion. I’d feel weaker and just generally more fatigued and exhausted.

“But the immunoglobulin has helped me so much. It’s helped me go to University, it’s helped me do my year abroad, and it’s helped me live a fairly normal life just like any other teenager or person in their early twenties.

“So if you can donate, it’s really an amazing thing to do and you’re helping so many people like me.”

How to donate plasma

Donation centres in London are currently located in Croydon, Twickenham and Stratford.

The plasma donation process generally takes just over one hour, including a questionnaire, some basic health checks and some drinks and snacks afterwards.

Unlike blood donation where you have to wait between 12 and 16 weeks to donate again, you can donate plasma as often as every two weeks.

Henry Jarvis, Twickenham Donor Centre Manager, said: “Please support this campaign and donate plasma at our centre – you will save lives.”

To donate plasma, visit www.blood.co.uk/plasma or call 0300 123 23 23.

Featured image credit: NHSBT