The issue regarding football’s lack of British Asian players has been a talking point for 30 years, yet much of the narrative has remained the same.

Even with all the advancement which has occurred in football over the years, the figures relating to British Asian representation are still harrowing.

The latest statistics show that only eight British Asian players made first-team appearances across England’s top four divisions last season out of a total 4,000 professional footballers.

Similarly, there is a huge gulf between the 0.3% of professional footballers who are British Asian and around 7.5% who make up the UK’s population.

These figures go a long way towards explaining why only four home-grown Asian footballers – Neil Taylor, Michael Chopra, Hamza Choudhury and Zesh Rehman – have ever played a Premier League game.

However, Riz Rehman, the PFA’s Player Inclusion Executive, who set up the PFA’s peer-to-peer mentoring programme around two years ago, is keen on shifting the narrative.

Rehman now spearheads the PFA’s newly launched official Asian Inclusion Mentoring Scheme (AIMS) and hopes to help increase the number of Asian players in professional football by focusing on the generation currently in the academy system and connecting them to the few who have already made it.

He said: “When you speak to current players in the game, everyone’s sick and tired of talking about the negativity about why there’s a lack of Asian players.

“Can we start celebrating the ones that are in the game and understand why they came through and what it takes to be a professional footballer?

“Yes, there aren’t many south Asian players or coaches, but don’t let that define you. It doesn’t mean that you’re not going to come through.

“If you’re good enough, cream rises to the top, what we’re going to do is give you a helping hand.”

The PFA’s scheme is a multi-level mentoring programme that assists British Asian footballers in the professional game, creating a structured network for young footballers where they can reach out to experienced players like Danny Batth and Neil Taylor.

This enables young players of South Asian heritage to seek crucial advice about a range of topics from both inside and outside of football, from dealing with setbacks, agents, position specific information, technical, tactical to how to approach coaches when they’re not playing.

Small details such as these go a long way in preparing potential future stars to follow in the footsteps of the trailblazers before them.

Ignored for long enough

Despite the lack of urgency towards the problem over the years, the reasons behind the alarmingly low number of British Asian footballers have been known for decades.

The issue was first recognised by the FA when it published a paper ironically titled ‘Asians Can’t Play Football’ in 1996.

It highlighted discrimination by scouts towards Asians with physical and cultural stereotypes, tackling previous misconceptions that there weren’t many Asian footballers because parents didn’t want them playing the sport.

While the FA eventually implemented a Bringing Opportunities to Communities strategy in 2015 to increase the number of Asians at grassroots level, measures have yet to be taken to educate coaches and scouts on their unconscious biases towards footballers of colour.

The severity of unconscious bias in football has since been supported by numerous first-hand accounts and studies, for example by Dr Daniel Kilvington, an academic in Media and Cultural Studies at Leeds Beckett University.

Kilvington explained to Prospect Magazine in 2019 how a white coach at a professional club had told him: “They don’t like physical contact, I think that’s their problem. Why are they good at cricket?”

Kilvington went on to add that the few British Asian players playing at a high-level, notably Neil Taylor and Michael Chopra, had “non-stereotypical Asian names or dual nationality”, which allowed them to evade stereotypes from scouts.

At the same time, Swansea City’s 22-year-old midfielder Yan Dhanda has also been vocal recently about the obstacles he has faced throughout his life because of his Asian background.

Dhanda, who spent five years in Liverpool’s academy before moving to Swansea and breaking into the first-team, told BBC Sport last year that the lack of British Asian players can’t get any worse.

Dhanda said: “There’s no point sugar-coating it and saying its fine, because it’s not, and I’m quite passionate that things need to change and Asian kids need to get more opportunities.

“When I was young I got a lot of racism. I got kids saying ‘you should be doing this job or should be doing that’, or ‘you’re not going to make it – you’re Asian’.

“There aren’t many Asian professionals because they’re stereotyped to be not strong enough. When people like me, Danny Batth and Neil Taylor are doing it then there’s no reason why they should be saying that.”

Despite smashing stereotypes about Asian players with his appearances in the Championship, Dhanda still suffered racist abuse online as recently as this year after Swansea’s FA Cup defeat to Manchester City.

Shifting the narrative

Even with all the various hurdles British Asian footballers continue to face, there are finally new signs that some positive change is occurring.

For the first time, a promising number of young British Asian footballers are coming through various academies across the country at the same time.

Rehman believes that the programme has already started to bear fruits, with more scholars and young players in academies today than ever before.

He added: “Some of the players we’ve supported have gone on to gain academy and professional contracts and their parents have called to say the informal and formal chats we’ve given them have been really helpful.

“Things have developed a lot. We’ve got more scholars in the game. That’s a good start and I hope now that if we can start showcasing some of our younger players, it will inspire some kids at the grassroots level to start playing football.

“Can we see more Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi and Sri Lankan players? That will empower people from their own communities.

“We’ve only got 15 British Asian academy players. The network is growing, so we are hopeful of the stats in this space becoming more positive. I think we need about 6,000 Asian players in the system for just one to come through.

“Ultimately we need more talented kids playing football in the good leagues to get scouted and then staying in the academy system once they get into a club.

“Historically, when entering into the system, Asian players and their parents have not had the networks in the game and this is where we feel the mentoring programme can bridge the gap.”

It’s clear that while the mentoring programme is starting to change the landscape, there is some way to go before we see a British Asian captaining England or winning the Premier League golden boot.

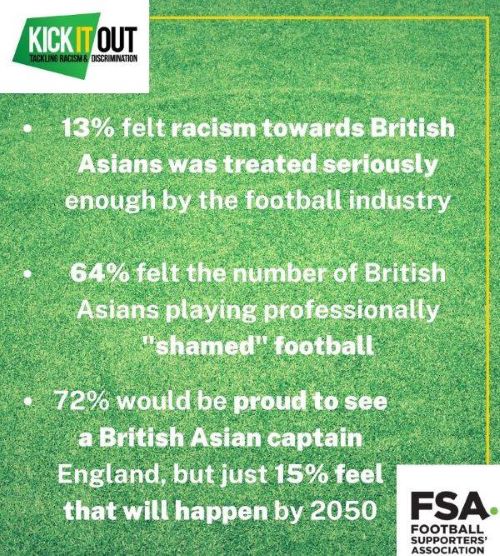

Significant change may be accelerated if the FA and organisations like Kick It Out implement more aggressive and innovative strategies to tackle the disparity in the game.

Holding social media companies to account, as more players in the game like Dhanda have called for, is another significant step in tackling racist stereotypes and online abuse which can be so damaging.

With foundations being laid by the likes of Rehman, a generation of British Asian youths are slowly but increasingly emerging in the game, raring to erode the age-old narrative that Asians can’t play football.

Featured image credit: The PFA