“Twenty-nine years ago we had a little boy who was born and it was just a freak occurrence that he had a haemorrhage in the middle of his brain.”

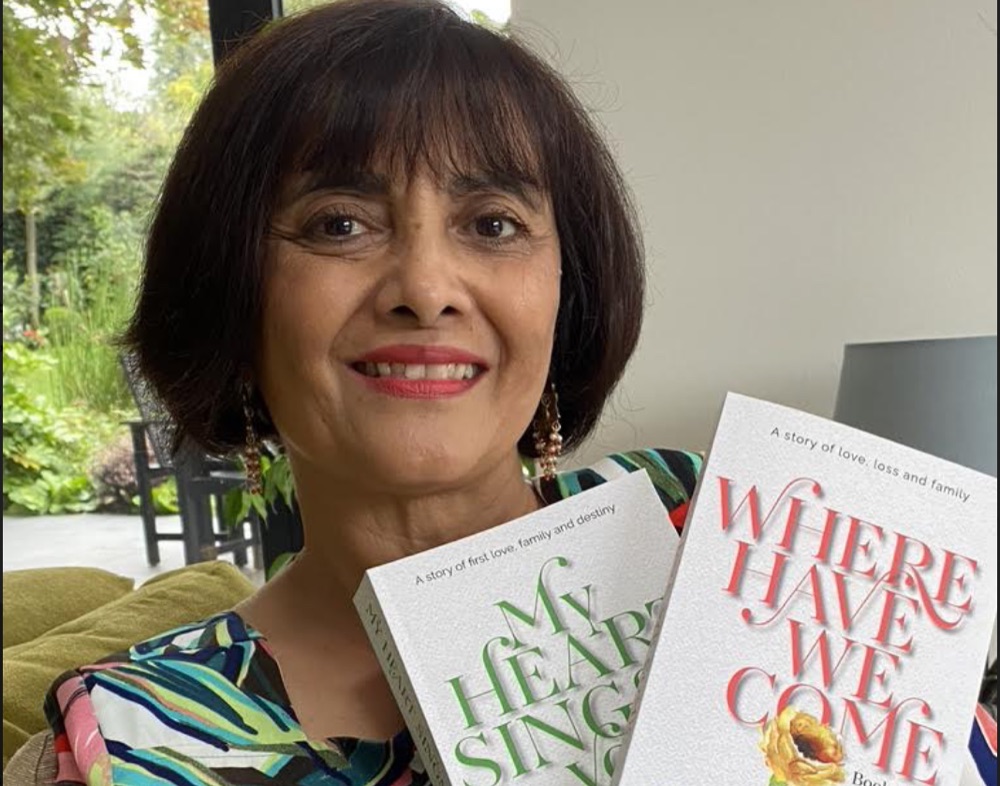

In 2006 when Saz Vora, who worked in production for news and current affairs and is from Ealing, went on a creative writing course, she was told to write a story about a moment in her life and she wrote about the loss of her baby son, Chetan.

Vora said: “When I was on that course and I said I what I wanted to write about, a couple of people said well nobody is going to be interested so I put it away.”

Despite these critics, Vora published that story Where Have We Come last year.

My Heart Sings Your Song is Vora’s second book based partly on Vora’s own experiences.

It follows the story of a mother through the birth of her severely disabled son, and how she later comes to terms with his death.

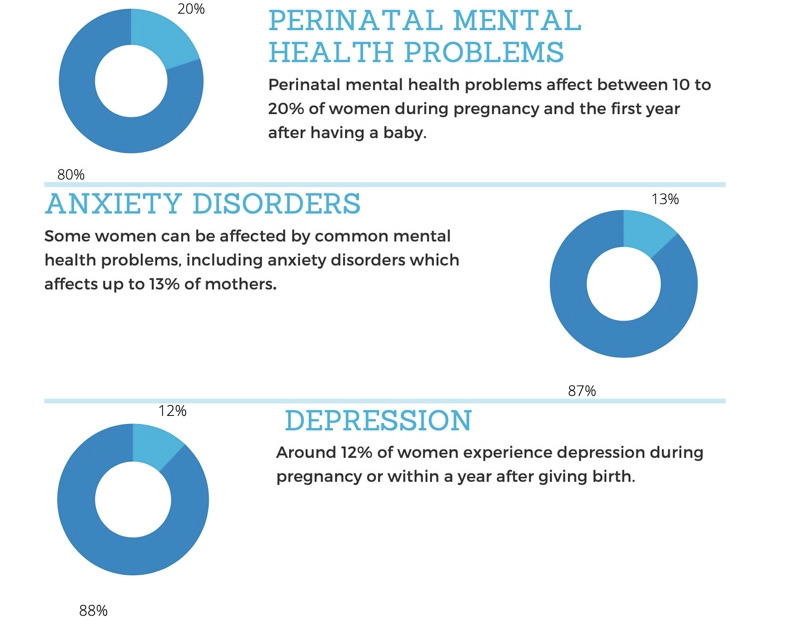

The story tackles difficult themes such as postpartum depression, child loss and the prejudices the character faces from within her traditional Indian Gujarati community.

Clinical Psychologist and creator of the Brownology podcast Dr Tina Mistry said that sometimes a blame culture exists within South Asian communities towards mothers.

Dr Mistry is also the co-founder of another mother story a platform that aims to amplify the voices of South Asian mothers living in the UK.

Some pregnant South Asian women are asked to adhere to specific diets, restrict travel and not wash their hair for cultural and religious reasons.

Even though these can be joyful experiences, restrictions placed on pregnant mothers can impact their mental well-being.

Vora witnessed this pressure first hand from her mother in law: “She said some really mean things to me about why my son was ill and why he died.

“The impetus to write the book came when I met up with a lovely lady who has a sick child and she was told exactly the same things that I was told: you need to do these fast days, your planets were not aligned when he was born, maybe it was because you ate this or because you washed your hair.

“There are some really weird customs you are expected to follow for the health of your child and mothers can be blamed if they don’t.”

Hassy Dattani, who works in medical research, said: “I recognised all of those attitudes and while I disagree with them I do understand why they are still held although this is in decline now.

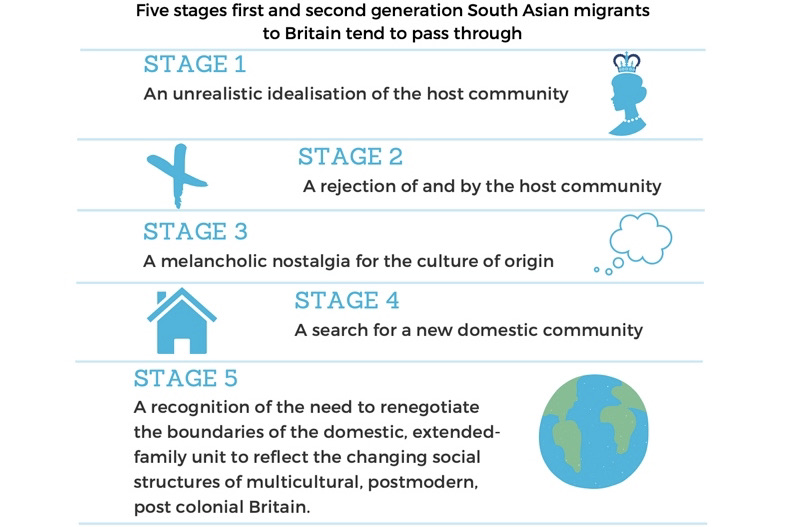

“I think that our people left their homeland with a view of how things were done. This became a frozen picture of the society they wanted to recreate in Britain.

“What they didn’t realise is that ‘back home’ things were moving on with the times.”

Vora added: “Some people are very entrenched in that we have to keep up with all of these traditions and rituals because it’s a way of keeping that going.

“I do not object to it, I think that it is a really nice thing to embrace but not when they are used by some to put pressure on women.”

Through her stories Vora is keen to challenge taboos surrounding mental health.

The Festival Coordinator of the UK Asian Film Festival Amandeep Dhillon said: “I think it is important for South Asian writers especially women to tell their story, or tell a story from their viewpoint, often addressing issues that many in the South Asian community shy away from.

“I think there needs to be more open discussion on many subjects that would otherwise be considered as a taboo such as domestic abuse, mental health, child-loss and sex.”

Vora received bereavement counselling after the death of her son, she suffered with anxiety and panic attacks.

Vora said: “Mental health should be just like your physical health it should be about your fitness in general.

“More and more people are beginning to realise that your mind and mental well-being is just as important as going to the gym and doing physical exercise.”

Dr Devon Campbell-Hall, a lecturer at Solent University who specialises in Asian British literature said: “It is common to have a subtle, much more insidious pressure from within a household or family, reminding the young mother that she is not quite good enough.

“Especially if she is from a lower caste, a lower slice of the hierarchy, she will be reminded of this position subtly and continuously, she will never escape that.

“One of the real challenges and that is that idea of a generic otherness, a generic South Asianess, because that would be like calling from the Shetland Islands western European – culturally, ideologically tradition wise it’s a different universe.

“But there are certain things that will be held in common i.e. that the mother-in-law will rule the roost.”

Vora said that writing the book helped her to address her grief and her mental health struggles and hopes that her story can encourage other mothers to speak out.

She added: “I used the South Asian lens as we have a very different dynamic, stories like these are necessary as it opens up the culture.”

Creator and blogger at The Brown Brontë, Shabnam Ahsan said: “It is vital to have South Asian stories told by South Asian writers both for younger generations of South Asian heritage to see themselves in books, and also to diversify the kind of stories that are seen as making up British culture.

“South Asian stories have been a part of Britain’s history for a long time and this needs to be embraced.”

Although South Asian voices may struggle to make themselves heard the rise of the independent press has made a real impact, writers like Vora can self-publish their stories.

Dr Campbell-Hall said: “The literary gatekeepers, the people who traditionally held the reins for whose name got out there and whose didn’t, have less power now.

“As writers we can bypass them we can take control of our own publishing, our own writing and the spreading of our word.”

Where Have We Come and Vora’s first novel My Heart Sings Your Song are available through Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Apple, Google, Rakutan Kobo, Hive and independent book shops.