By Madeleine Coffey

August 15 2020, 17.25

Follow @SW_Londoner

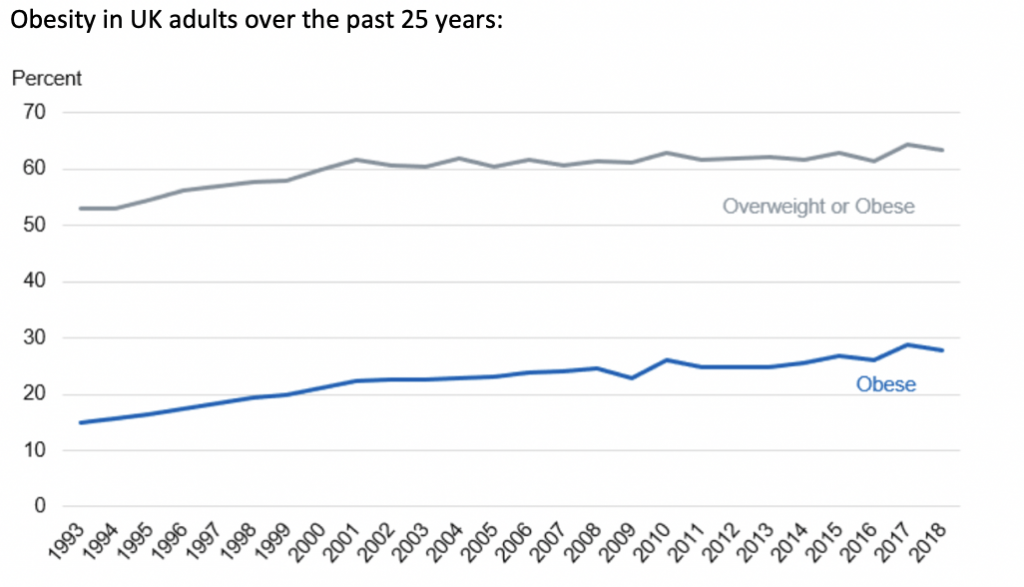

In a bid to combat the devastation of a potential second-wave, the government released a strategy to target rising obesity this month.

Research by Public Health England (PHE) revealed that excess weight placed people at greater risk of hospital admission and ICU in the face of COVID-19 and prompted Johnson’s new obesity strategy.

Obesity strategies have chequered policy in recent years – from Cameron’s curbs on food marketing and advertising in England in the summer of 2016, to May’s plans to ban fast food advertising before TV watershed.

However, this presents a sharp U-turn for Johnson, who only last year rejected tax on junk food.

The strategy includes a ban on junk food adverts before 9pm and the sale of chocolates, crisps and sweets at checkouts.

Nutrition scientist Dr Simon Steenson, of British Nutrition Foundation, said: “The proportion of people living with obesity is highest among the most deprived groups in our society, and children from the most deprived areas of England are more than twice as likely to be obese as those living in the richest areas.

“Given the scale of the problem, it is likely that further action involving many different stakeholders throughout our food system, as well as government and the medical community, will be needed in order to have a significant impact on obesity levels.

“This includes addressing the social inequalities we know are associated, especially in light of the serious economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Other measures include displaying calories on menus in restaurants and pubs, including for alcoholic drinks.

Although health campaigners have welcomed the proposals, many have questioned whether they put too much emphasis on individual responsibility for obesity, rather than addressing health inequalities.

The same PHE research that prompted this strategy also concluded that people living in more deprived areas had higher rates of infection and greater mortality of COVID-19.

The campaign has been criticised for perpetuating such inequalities – for example its online and app basis means the 12-week programme will not be accessible to those living in digital poverty.

In response, the Department for Health and Social Care put out a statement which said: “The campaign will reach and support BAME groups that it knows has higher rates of obesity, working closely with community and faith organisations to develop and share its messaging.

“It includes messaging that will resonate with different communities and much of the advertising has been translated into languages such as Hindi, Gujarati, and Urdu.”

Lucy Perrow, a spokesperson for British Dieticians Association (BDA), and registered dietitian and obesity expert, said: “An intention to ‘focus more on public health and prevention’ is welcome, but the focus must be backed up by ring-fenced, additional, long-term public health funding.

“The emphasis on losing weight as a patriotic duty is unfair and risks further stigmatising those who struggle with their weight, despite sustained effort.

“Individual efforts to achieve and maintain a healthy weight in a system which fails to recognise the impact of emotional distress and food insecurity on eating behaviour in combination with an environment which promotes over-consumption and a sedentary lifestyle are likely to be overpowered.

“The NHS BMI calculator and 12-week programme are not new, and evidence of the efficacy of campaigns is limited apart from raising awareness of the issue.

“However, it is unclear that it is lack of awareness that is the problem, rather than the practical difficulties of managing to be adequately active and nourished, in and affordable way, on limited time and resource.”