By Tess Colley

July 28 2020, 15.00

Follow @SW_Londoner

As London begins to stir from the depths of lockdown, and the financial impact of the pandemic begins to take hold, it is a time of anxiety and uncertainty for many.

Having been confined to our homes and the surrounding areas for months, our relationship with the areas we live in has inevitably shifted.

The lockdown, and the period of subsequent easing, have been a source of national anxiety and uncertainty – a shared experience, but also specific to our own local corners of the country, and specific to our own mental wellbeing.

Van Gogh and south London

In Stockwell, south London, the Van Gogh House has re-published At the crossroads with Vincent, an ‘audio-walk’ intended to give anyone, but particularly those isolating or struggling with the mental impact of being cooped up, an invitation to walk with no set destination or purpose, and to think reflectively.

For those in Stockwell, it also invites the community to see the area through the lens of a 20-year-old Van Gogh, who moved to the area in the 1870s from his native Netherlands.

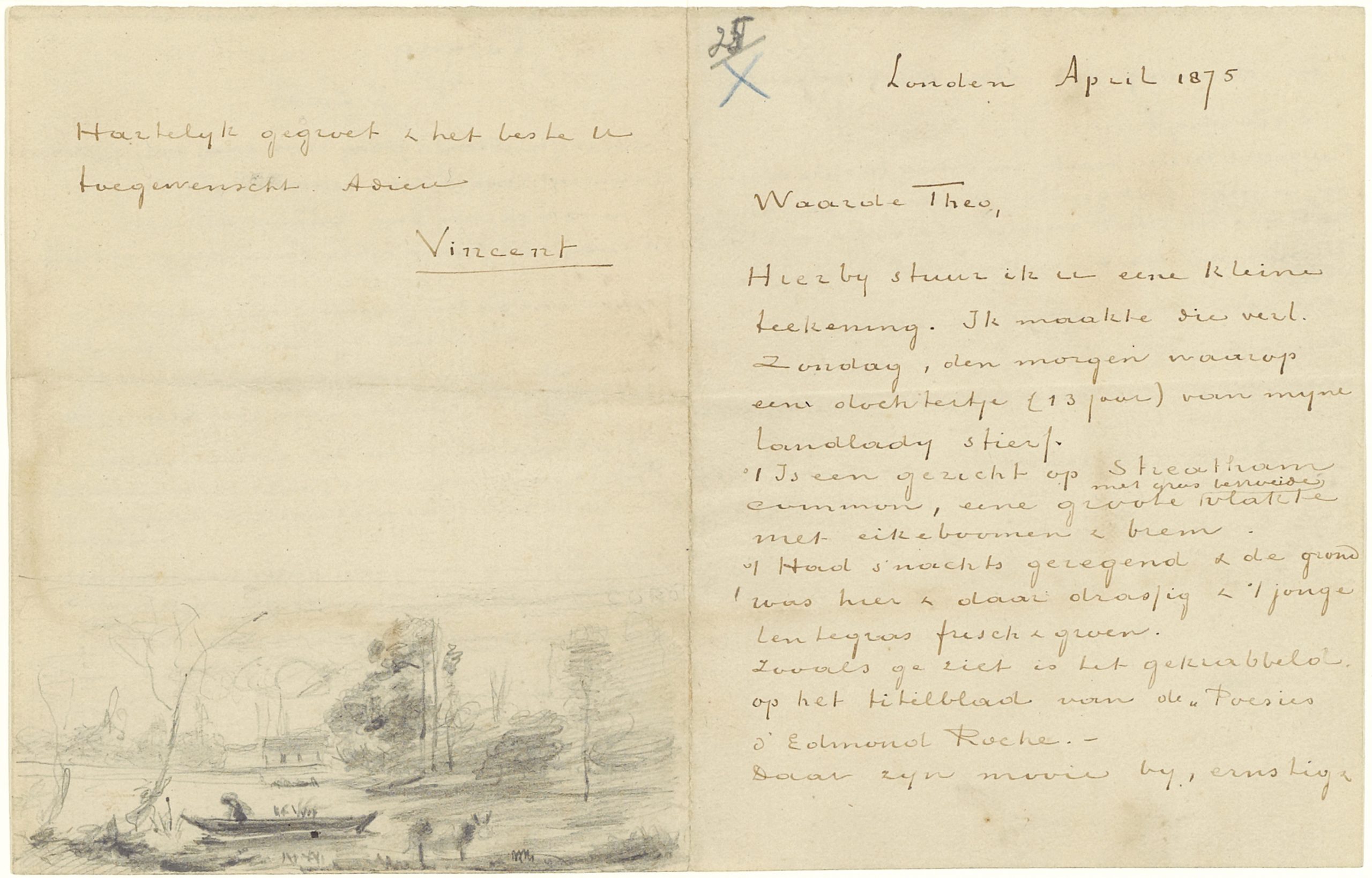

It is a little known fact that the world-famous expressionist painter spent a year of his life living on 87 Hackford Street, then a guest house, which he used as a base to hone his artist skills and amongst other things, go on long walks.

The house is now graced with a blue plaque and hosts artist residencies in addition to guided tours, exhibitions and events in celebration of its famous ex-tenant.

The audio-walk first debuted in 2014 alongside an installation in the Van Gogh House, after being commissioned by the London arts organisation Artangel.

When lockdown came to London, it was decided to re-publish the Van Gogh audio-walk online during lockdown as a way for people to continue to engage with the arts during a time when all galleries, museums, cinemas and theatres had closed their doors.

At the crossroads is made of extracts from letters Van Gogh wrote to his brother whilst living in London, as well as bits of creative writing which came out of workshops hosted by Tottenham-based artist R.M Sanchez-Camus with CoolTan Arts, a charity which focused on arts and mental health before it closed in 2018.

He said: “Often if we feel upset about something or need some space, we go for a walk.

“This can be so different in urban spaces or cities where a lot of our life is directed around getting from A to B.

“Walking without purpose is not something that we often do.”

The walk is specifically designed around people who have suffered from mental illness, as Van Gogh himself did, and includes a series of actions, such as finding something on the walk to bring home as a souvenir.

When listening to the audio-walk there are times when the distinction between Van Gogh’s words and those of the workshop’s contemporary Londoners is blurred – a move which was very much intentional on the part of Sanchez-Camus.

“It was a way to show that the words of this great artist held in high esteem, are not any different to anyone else’s. It elevates the thinking and the words and value of the people we did the workshops with.

“It’s a democratising way of creating culture.”

The question of how we relate to culture and art is not a new one, but it is cast in a new light in the wake of the pandemic which threatens the future funding of much of the UK’s arts industry.

For Sanchez-Camus, he holds that it is art which is relevant to communities and society at large which will rise to the occasion as the industry finds its way through the financial fall-out of the pandemic.

He said: “The crisis that the arts is going into has been coming. The pandemic didn’t create it, it’s exasperated it.

“The arts are a reflection of who we are as a society. So if the arts are not undergoing a crisis, it’s not paying attention, for we are as a society undergoing a crisis and we have been for some time.

“When we talked with the workshop group, we said how when you are in a mental health crisis it can be hard to know you’re in it. That’s where we are now, we are living it.”

Mental health and the arts

It’s 130 years this month since the death of Van Gogh. Despite his fame, he only found it after death, and lived a life troubled by mental illness – he is said to have suffered from psychosis.

He died in 1890 after ending his own life.

According to the Mental Health Foundation it is estimated that one in six people in the past week experienced a common mental health problem.

The Foundation has published research on how the arts can improve a person’s mental health, through offering help, promoting well-being, and creating a space for social connection.

Jolie Goodman, programmes manager at the Mental Health Foundation, and an artist herself, said: “From our research at the Mental Health Foundation we know the lockdown had a larger impact on the mental health of people aged under 24, the unemployed and people with existing mental health conditions.”

On why the arts can help with mental health she added: “Making art, looking at art and attending virtual arts events, are all ways to experience other realities.

“Whether you see yourself as creative or not art can be a way to express emotions that are very hard to put into words.”

However, for people to help improve their mental health through arts and creativity, the arts need to be accessible to the masses.

Commenting on this, Goodman said: “People without digital access will have been further excluded from the arts during lockdown. As an artist, I think that it is important that the issue of access to the arts is central to arts recovery after the different stages of the pandemic.”

The arts and access

The arts industry is often criticised as being elitist, or inaccessible to those from poorer backgrounds.

For Sanchez-Camus, while historically the arts have put up barriers, he sees technology and audience participation as being key to bringing people to the arts and making them feel like they are something for them.

The internet has made everyone a curator – if they want to be – with YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram some of the most popular platforms where overwhelmingly younger people create what they want to see.

Sanchez-Camus said: “For large-scale institutions like museums and galleries, this is re-framing the way they present artwork and bringing in much more participatory models to make their collections more relevant.

“People don’t want to observe anymore. People want to come and participate. It’s not enough to say here’s the collection, here’s these great artists, come and walk around and look at it. You now need to make a different offer.”

This, he says, will be even more important in a post-pandemic world.

At the crossroads is one such piece of participatory artwork as in the artist’s view, it ‘becomes a very small invitation to people to be creative. When you go on that walk you’re not just listening to a work of art, you’re participating’.

Kesia Chalmers, 25, is a Vauxhall resident who recently did the audio-walk around the same streets Van Gogh lived in.

On completing the walk she said: “I feel so peaceful. Though I was walking up main roads, it felt like taking a walk through varied, colourful countryside.”

Life after Covid-19

As London came to a standstill, and walking outside was permitted for only short excursions, Livia Wang, creative director of the Van Gogh House, re-published At the crossroads through the House’s website, believing it to be more relevant than ever.

She has been working on the Van Gogh House as project for seven years, and said: “It’s been really brilliant knowing everyone in the local community and feeling part of it, feeling embedded in it.”

For her, although Van Gogh is considered a world great, there is something about his fame which makes him accessible.

“A few times I’ve been outside the house, maybe putting the bins out, and people just come up to me and talk to me about Van Gogh.

“I feel there are very few people who make others comfortable in talking about a piece of art if they’re not artists.”

However at the moment she is unsure when the house will reopen. As a family business running the house as a private company, she says they are ‘finding it really really hard to access any funds’.

Despite this, and the difficulties facing London’s arts and creative institutions more widely, both Wang and Sanchez-Camus strike ultimately positive notes.

Wang also runs the near-by San Mei gallery which has just re-opened with a new exhibition running until August 8, and Sanchez-Camus is currently involved in a project with national arts charity Art Fund making participatory toolkits for museums to help them with engaging visitors.

“We’ve all been afraid to leave our houses,” he comments. “And now we’ve got to all pack into a museum or theatre? How do you get people back in?

“The way you start getting people back in is through meaningful engagement.”

Find out more about Stockwell’s Van Gogh House online @vangoghlondon