By Rhodri Morgan

May 4 2020, 12.15

Follow @SW_Londoner

The coronavirus pandemic is re-writing modern politics.

Halls of global parliaments are now decadent echo chambers. Partisans temporarily silenced.

But for Italy and its history of fascistic popularity, the pandemic could prove a generation-defining political bellwether.

In recent years, Italy’s foremost far-right party, Lega, led by the outspokenly xenophobic Matteo Salvini, reigned as Europe’s undisputed face of nationalism, absorbing the centre-right ground previously occupied by Silvio Berlusconi’s now struggling Forza Italia.

Despite Salvini’s failure to oust incumbent Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte in August, Lega remains Italy’s most popular party, with a 14% favourability lead over nearest rival, centre-left Partito Democratico (PD) at 2019’s close.

But that lead has slipped 8% to 29% in the first four months of 2020 marking a lack of support for Salvini’s ‘pandemic politics’; decrying free movement, blaming African migrants for Italy’s outbreak and calling for Conte’s resignation.

“His policies, especially on immigration, became redundant overnight,” says Martin Bull, Politics Professor at Salford University.

“Salvini could have been Minister of The Interior during this crisis, but his indiscretions last year prevented that and now oppositional politics has died a death.”

Conte’s leadership is at 71% approval, a 10-year high for Italian leaders, and 94% of Italians support his handling of the crisis that has also earned him international credit.

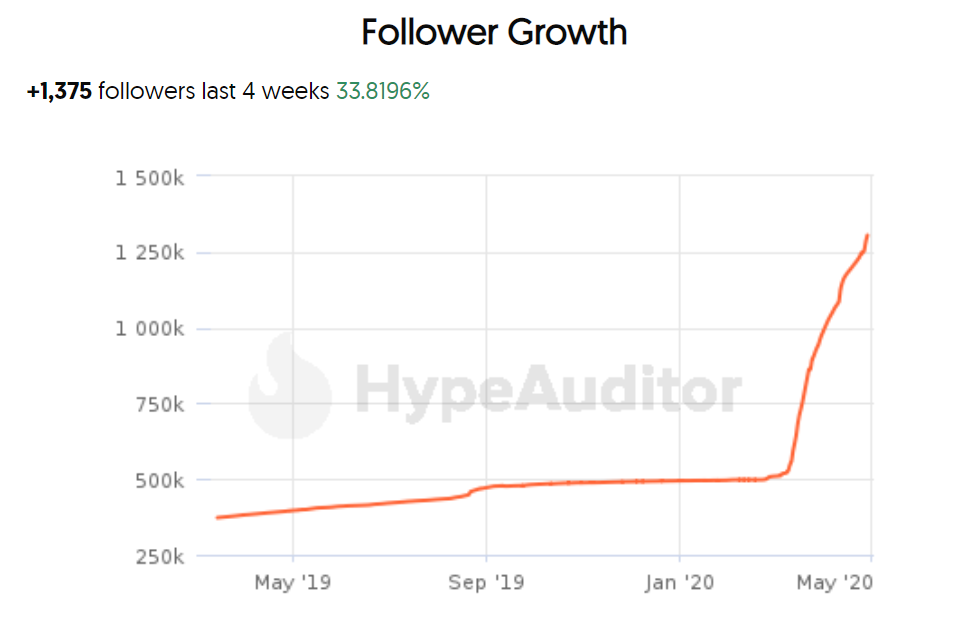

His handling of the crisis has also seen an enormous growth of his personal brand with his Instagram followers almost tripling between March and the end of April this year.

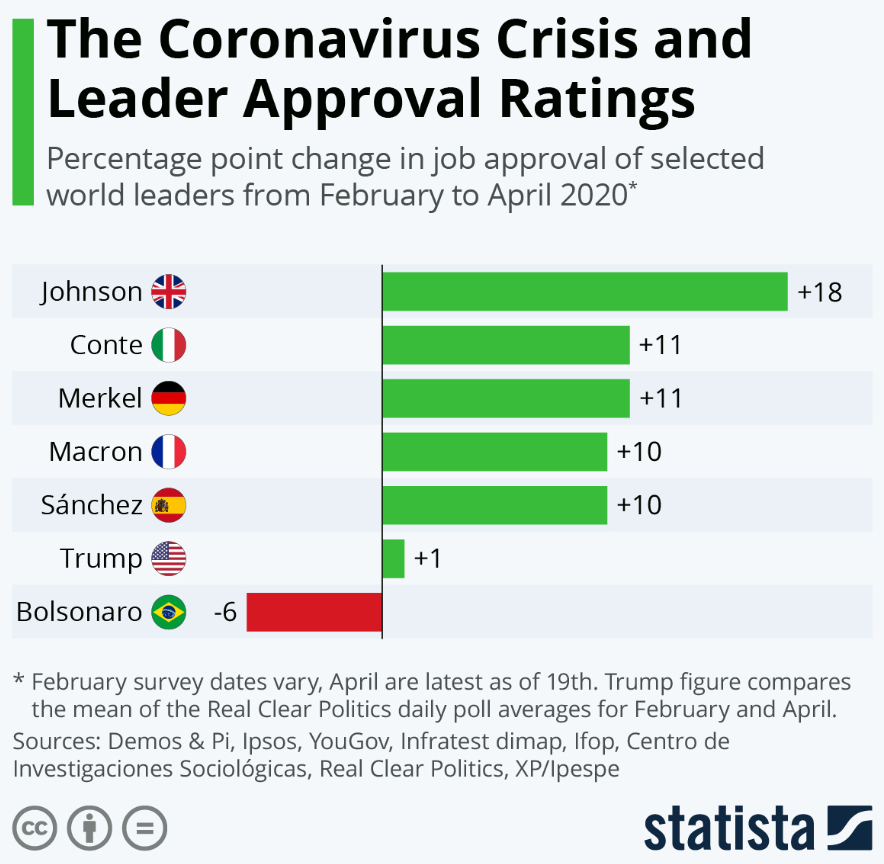

In the context of other world leaders, Conte ranks joint second highest in improvement alongside German Chancellor Angela Merkel, seven points behind UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson.

Against a swell of popularity for Conte, Salvini and Lega are undeniably losing ground.

But as the pandemic’s financial implications worsen, both they and Italy’s secondary far-right party Fratelli D’Italia (FDI), could capitalise on entrenched euroscepticism lingering from the 2008 financial crisis.

Initially, Conte advocated using the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), a €500bn fund established during the 2012 debt crisis, to ballast Italy’s economy.

But, knowing Rome’s deep suspicion of the ESM regarding national sovereignty, he opted instead to pursue “coronabonds” – jointly issued debt underwritten by eurozone member states – an approach Salvini decried as appearing “cap in hand”.

In a second and decisive reversal, Italy’s Finance Minister Roberto Gualtieri signed a €500bn economic relief package early last month without specific reference to the institution of “coronabonds” but detailing cooperation with the ESM.

At a meeting on 23rd April, the EU Council voted to “sideline” using “coronabonds” following continued opposition from the German and Dutch opting to centre their $546 billion rescue plan around the ESM.

To make matters worse, Italy’s fragile economy is now hitched to the EU for the foreseeable future, providing ammunition for Conte’s detractors and even sparking criticism from the co-governing Five Star Movement.

Conte’s long-term future is uncertain. Like former Prime Minister Mario Monti, he is not a politician by trade. Many, including Professor Bull, expect him to learn from Monti’s mistake and make a Churchillian post-crisis exit rather than pivot into mainstream politics.

Others, like political analyst Loretta Napolini, see the crisis as a turning point in the nation’s conscience and Conte as Italy’s future.

“I see a continued consolidation of Conte’s coalition, maybe for 10 more years,” she said.

“The centre-right has gone. Like Berlusconi, Salvini belongs to history, and everything that happened before the pandemic seems like it belongs to the last century.

“He will disappear within two years.”

But despite Salvini’s failed challenge at Conte last August ruling out elections until 2023, should Conte stand down, the party-piecemeal cabinet may be vulnerable to right-wing pressure for the Parliamentary majority.

Alongside Lega’s waning support, FDI’s popularity has doubled from June last year to 13%, just 2% away from Italy’s long-time second favoured populist party, the Five Star Movement.

For post-coronavirus Italy, a recession reminiscent of 2008 is likely – another echo chamber.

The question is whether the voices of the extreme right, familiar to its afflicted population, will unite and swell to a decisive crescendo.

Featured image shows The Chamber of Deputies, one of Italy’s two Houses of Parliament (sourced from Unsplash).