After 17 years of weekly demonstrations, one group of Zimbabwean activists in London shows no sign of capitulation in its long span of protest.

The ZimVigil activists have gathered outside Zimbabwe’s embassy on the Strand every Saturday since October 2002 to demand free and fair elections in their home country, and have felt a recent sense of urgency to voice their anxieties about the state of Zimbabwean democracy.

The activists danced and sang protest songs, but the jubilant atmosphere of demonstration was undercut by a sense of the cruelty they were protesting: massive banners with the words ‘rape’ and ‘torture’ surrounded the protestors even as they played drums and laughed together.

December marked one year since Robert Mugabe was ousted in a coup by members of his own ruling party, ZANU-PF, and replaced as president by a party rival, Emmerson Mnangagwa. Mnangagwa is known by Zimbabweans as the Crocodile, a nickname he earned in the Rhodesian Bush War of the 1970s for his infamous political cunning, and as founder of the Lacoste faction of his party.

Bigboy Sibanda, 40, said: “There has been no change at all, since Mnangagwa was Mugabe’s right hand man. When it is the same party there will never be any change. I think the election was rigged. There was intimidation. There was bribery. There were people in the villages who were being given money to vote. It was a sham. It was disgusting.”

These protests are defined by an undercurrent of mourning: there is a shared awareness of the horror of what continues back home, and the protestors’ website hosts a long list honouring those killed in political violence in Zimbabwe since April 2000.

The protestors expressed their sense of unease at the new regime, or perhaps more accurately, the renewed regime. In their eyes, little has changed during Mnangagwa’s term of office; in their eyes, the democratic situation in Zimbabwe has drastically worsened in the past year.

One particular motif recurs through the activists’ rhetoric: a sense of shared responsibility as a diaspora, the desire to provide a voice for those deprived of one back in Zimbabwe.

Anna Rukwava, 29, declared that this was her primary motivation to protest. She said: “Back home, Zimbabweans don’t have a voice, so we are the voice for them here, to let them know that we are still caring for our country and we want the government to change.”

The group’s co-founder, who has attended protests since they began in 2002, is Rose Benton, 73, who described how the human rights question in Zimbabwe has faded from popular scrutiny in Britain. Her worry is that donor fatigue means the problem is increasingly going unnoticed. During the 2008 elections a decade ago, upwards of 200 people would attend Rose’s rallies; now, only a tenth of that show up.

The ZimVigil activists are deeply concerned about apparent British government complicity in sending Zimbabwean asylum seekers back to a country which Rose characterised as deeply hostile to any expression of anti-government thought. One protestor said he has been in and out of Home Office detention over the past couple of years.

Rose said: “The newest thing that has happened with the new government is that they are in contact with the embassy here about asylum seekers. Before there was no contact.”

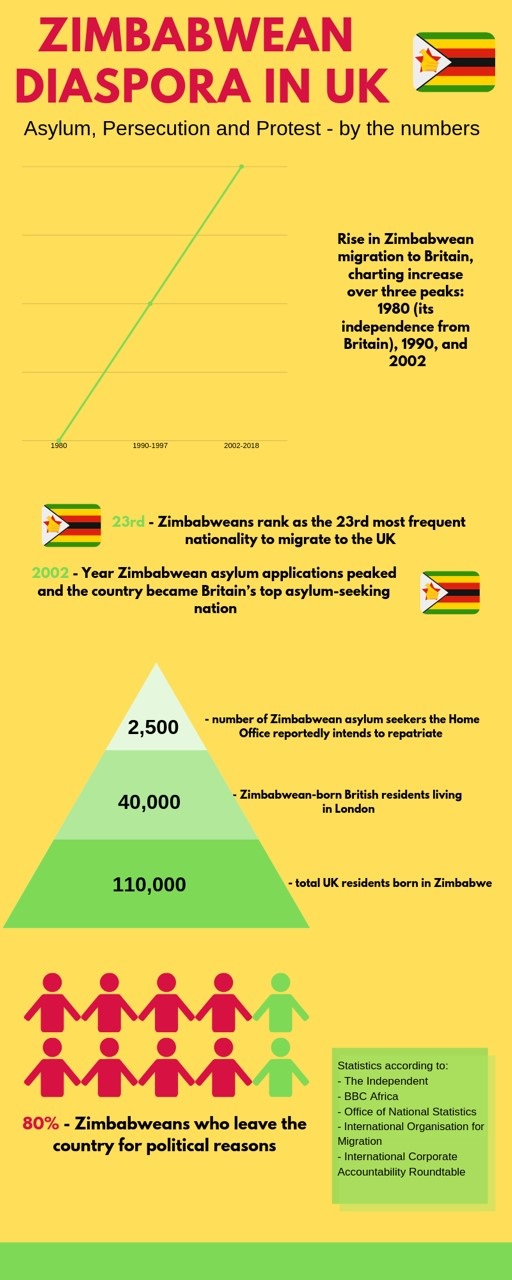

Zimbabwe has been in the UK’s top ten asylum receiving nations since 2000. Political instability means that there has been a huge rise in Zimbabweans fleeing to Britain for asylum. Around 40,000 live in London, with an estimated 80% leaving their home country for political reasons.

In December it was reported that the Home Office had invited Zimbabwean government officials to interview asylum seekers who have fled political persecution, as part of an apparent agreement that Britain should repatriate around 2,500 asylum seekers.

Rose traced a change in the embassy’s relations with the British government, pointing out that since human rights abuses under Mugabe attracted condemnation, ‘the embassy really wants acceptance now’. She suggested that foreign money has kept the government afloat, and it was therefore predictable that Zimbabwe is working to make relations closer with the Home Office here.

With regard to reports of asylum interviews conducted by Zimbabwean officials, a Home Office spokesperson said: “A routine redocumentation interview event took place in Sheffield on Tuesday 4 December.”

Rose, about to begin her seventeenth year of protests, provided a sense of the sacrifice her demonstrations have precipitated. She fears she will be unable to re-enter Zimbabwe, and that soon she will have to stop leading the unrelenting protests against government-sanctioned abuses back home. After almost two decades of duty to her cause, she said: “It is time for me to step down and let other people take over. I have had enough.”

Nevertheless, the ZimVigil activists show a keen awareness of what has become a neglected issue, and a firm belief in the importance of the diaspora’s duty to vocalise anxieties which have persisted after Mugabe’s regime and into this new development in Zimbabwe’s history.