“I don’t tell her. I don’t tell her but she’s starting to feel that we’re poor.”

Maya sits in Hammersmith & Fulham Food Bank’s satellite branch in Shepherd’s Bush, tears slowly rolling down her face as the conversation turns to her 10-year-old daughter.

“She’s never seen me here. I come when she’s at school, but she knows. My daughter likes to read a lot and she used to ask me when a new book comes out to buy it – I would go out and buy it for her.

“Now we don’t. Now I don’t have money and she starts to tell me to go back to work.”

The three carrier bags of food on the chair next to her will not be enough to sustain her and her daughter for the week, but Maya’s arthritis, an appointment for which she has just left, prevents her from carrying any more.

The bags contain oats, tuna and canned food — but no fresh vegetables, as the food bank is simply unable to hold enough.

A total of 37 people are fed in two hours on this day, but this is a low headcount by usual standards, attributed to the fact it’s 26 degrees outside. Most of the time, it’s ‘breathless’ in here, members of the volunteer workforce say.

To supplement what she takes home, and add nutrients to ensure her liver does not suffer further complications from its high fat content, Maya must improvise. Walking home, along streets lined with Ferraris, Range Rovers and Aston Martins, she cuts into a local park to pick dandelions and herbs for soup. She visits a market stall and buys lettuce for salad. It won’t be fresh by tomorrow, but she must make it last a week.

This is her 11th month using the food bank. She has, she claimed, been coming longer than anyone else.

“Nobody plans to be at a food bank,” said Hammersmith & Fulham food bank manager Daphine Aikens. “Nobody plans to be in trouble like this, nobody plans to ask for help, nobody plans to go hungry.

“It’s something I always felt very strongly about, but I didn’t think there was anything I could do because it all seemed so far away. I always thought poverty was a problem for others, for third-world countries. Then I realised it’s a local problem.”

As Daphine speaks, her food bank, along with all 427 other Trussell Trust-associated banks, is preparing to release its usage figures for the 2017-18 financial year. The news is not good.

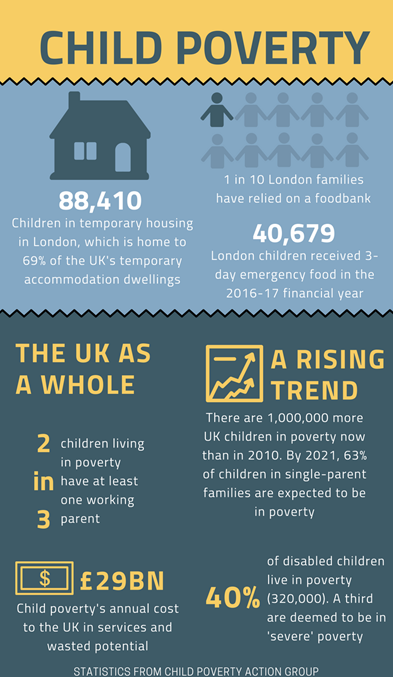

Food bank usage in the UK is up a record 13% in the last 12 months. The Trust, in charge of the only coordinated food bank network in the UK, handed out more than 1.3m food parcels in that time. Research released this month by the Trades Union Congress (TUC) estimates 3.1 million children – all with working parents – will be below the breadline this year.

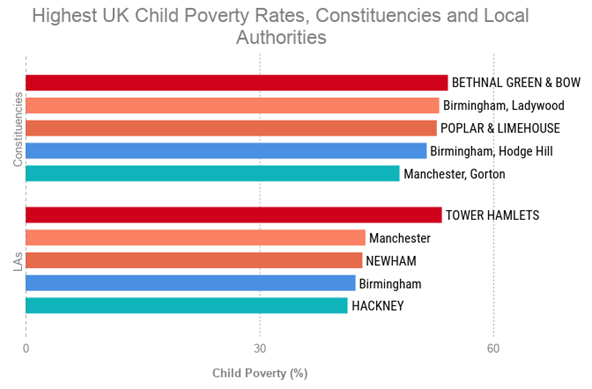

One million more children are in poverty now than in 2010. Child Poverty Action Group (CPAG) statistics show that in London alone, 37% of children (700,000 in total) are now in poverty.

Poverty is defined as living in a household with less than 60% of the UK’s median income, a mark which varies from £17,100 a year for single people to £18,900 for couples with two children, according to the Joseph Rowntree Foundation. Two thirds of those 700,000 children have a parent in work.

For people in Daphine’s position, this comes as no surprise. Her own food bank handed out 100,250 meals in 2017-18, roughly equivalent to 10,000 parcels and a 250% increase on the figures from 2015-16. More than a third of the parcels were taken home by children.

Elsewhere in south west London, more than 40% of the 4,690 people who used Wimbledon Food Bank in 2017-18 are children, and rates across the region are up. In Westminster, the second-richest borough in the UK, usage grew by more than 22% from 2015-16 to 2017-18 – a fifth of users were under the age of 18. Norwood & Brixton saw a 50% rise, with 3,993 children fed last year.

In April, the CPAG reported teachers across the country were filling their pupils’ lunch boxes with extra food to keep them energised throughout the day. Daphine, who quit her job in 2010 to found Hammersmith & Fulham Food Bank, fears for the long-term impacts of the recent rise.

She said: “[Poverty] is a problem that goes back to the very beginning, to what kind of start you get in life, those first four, five years of your life.

“What kind of education you get, whether you’re encouraged, whether you get a chance to develop and be the best you can be.

“And then what is there for you after school – are there good jobs out there? What’s your accommodation like? What’s your housing like? It’s a big problem.”

Poverty affects children in different ways to adults, as Maya notes when discussing how she tries to provide for her daughter, who she asks not to be named.“I am not buying her clothes now,” she said. “Her clothes are too small for her. It is the end of the year, after summer term we will start to struggle.

“I have all the clothes I need, I used to have a lot. I am not growing, but my daughter is.”

Being in poverty is not just about an inability to buy enough food, or enough clothes, or afford the bus service to redeem a food voucher.

Fowzia Ahmed, who moved to England from Italy with her mother and three younger siblings in 2014, sees the impact first-hand in housing, too.

As a member of the steering group of the ‘ChangeIt!’ campaign, run by the Children’s Rights Alliance for England (CRAE) to highlight issues within temporary accommodation, she speaks from experience.

Temporary accommodation is usually limited to six weeks, with families housed in bed and breakfasts, hoping to be permanently housed from then on. However, due to the lack of affordable and social housing, this is not the reality.

The Ahmeds have been in temporary accommodation since June 2016, one of 43,550 families in London in this situation. The capital makes up 72% of the UK total. More than a third (1,200) of families in B&B accommodation have been there for more than the six-week limit, CRAE figures show.

The accommodation these families are provided with only deepens the problems.

“There is mould, there is ice on the ceiling in my brother’s bedroom where he sleeps with my mum, from how cold the accommodation is,” said Fowzia, 19, from her current location in Luton.

“There are two mini fridges and they’re really small, we have to put all the food outside on the balcony. There’s no space in the kitchen – obviously food poisoning could happen.

“It’s a really bad neighbourhood, there are people that smoke cannabis and throw cigarettes from their balconies which end up in our food.

“It’s really unsafe. People just come in and break the main door, there are so many families and every day when you go down the door is always broken.

“Sometimes you find people throwing up in the lift. On the windows outside just before the lift, someone tried to burn them, you can tell. That’s just horrible because you don’t know who it is – there are cameras everywhere but no one really cares.”

CRAE participation manager and ChangeIt! leader Maria Stephens tells of families blighted by bedbugs, forced to share a single bed and being placed in areas where drugs are rife.

She said: “There was a family where one of the daughters described having to share a bathroom – quite a common thing – and having to deal with things like faeces being smeared all over the walls on a daily basis while she’s trying to get ready for school.

“They have to use that bathroom because there are no hygiene standards and nobody keeping it clean.”

While the impacts of poverty are many and various, the causes behind it, and indeed the recent swelling of people deemed below the breadline, are often pinpointed to two key factors by these interviewees: the introduction of universal credit and changes to benefit allowances.Universal credit, first introduced in October 2013 and progressively rolled out across the country since, combines six previous benefits into one monthly payment. Although appearing far more simple than the previous setup, it also involves recipients being forced to wait five weeks from application approval to receiving their first payment. Or, as Daphine Aikens points out, sometimes even longer.

She said: “The reality is that people are waiting eight weeks, 10 weeks, 12 weeks from application. Even that five-week wait is just too long. If you don’t have any money, five weeks is a really, really long time to manage, especially as your rent isn’t being paid.

“If you’ve got no money, no savings account, nothing to fall back on, what do you do during that time? You borrow, you go without, and then you find that actually it’s not five weeks, it’s another two weeks or five weeks, 10 weeks, 11 weeks, 12.

“You can’t pay your gas and electric, you can’t pay your council tax, you can’t pay your TV licence, you’re borrowing for food, you’re borrowing for travel expenses, the kids need new school shoes.”

In the last year alone, areas where universal credit has already been rolled out experienced a staggering 52% increase in food bank usage (four times the national average), according to the Trussell Trust.

The five-week wait is not the system’s only problem. As many have expressed, shifting benefits online has also removed a significant portion of its humanity.Stephan Wiedmer, branch manager for Crosslight Debt Advice in Hammersmith & Fulham, calls the system a ‘black box’.

“If you’re a standard case and everything goes smoothly and you’re quite well-equipped with internet access and a computer, universal credit is easier for you to use,” he said.

“But as soon as you are a complicated case or you have personal barriers of language, learning disabilities, addictions or simply families who are under so much and now have to do everything online. It’s more anonymous and some people struggle with that.”

Maya, who arrived in the UK from Lebanon in 1992, was forced to wait three months for her universal credit application to be completed. The first payment eventually arrived in February last year. It stopped in June. The reason she no longer receives it, she claims, is that she still shares a tenancy agreement with the father of her daughter, despite the two never having been married and separating as a couple more than a decade ago.

“Previously it was the same and it was no problem,” she said. “The council refuse to make him move and refuse to re-house him, they stopped my money. He tries to move and he is applying, but they won’t move him.

“They took his name from the housing waiting list. About two months ago they sent him a letter saying he can build [his own home], but when we sent for the password so he can build they said no, you are not allowed.”

For Fowzia, the feeling of a crackdown being initiated by universal credit is also present.

Aged just 16, she was forced to act as translator for her mother in council meetings to decide their housing benefit allowance, despite having limited English skills herself.

Not knowing they were eligible, the Ahmeds missed the deadline to apply for an increase in housing benefit, to cater for Fowzia’s brothers.

One of the brothers has a genetic disease and the other has had multiple operations on his legs. The Ahmeds ended up in bed and breakfast accommodation for six months.

Fowzia said: “That gave me even more anxiety – I felt like it was my responsibility, my fault that we were in that situation because I was the one who translated for my mum that day.

“I was aiming to get into university and study law, but it didn’t happen, I had so many exams to do in second year because I was retaking the ones from the previous year. All of the anxiety about what’s going to happen in the future, where are we going to be, it didn’t help, and it didn’t work out.

“During that entire time, when we didn’t have anything, we went into debt – seven thousand pounds.”

The impacts were compounded by the accommodation they were provided with, which was not fitted with cooking facilities. Fowzia and her family were forced to eat at McDonald’s and Subway every day until they could solve the problem.

The brother with the genetic disorder – four at the time – continues to suffer from the holes in his nutritional intake, two years on. “He’s really skinny, he’s still struggling with his eating.”

Another shared emotion among many in poverty is the shame they feel. Despite the rapid increase in those attending food banks, attending a food bank is still a source of great embarrassment for many.

Caroline Ferrier, manager of Richmond Food Bank, which fed 2,500 people last year and a third of whom were children, sees the problem particularly in parents.

“Some people will walk in and immediately burst into tears,” said Caroline, who like Daphine draws heavily on her Christian beliefs in her work. “They never imagined that their life would become so difficult that they would need to come to us.

“We had a lady visit because her relationship had ended. The income she received had to support her ex-partner and her household. She had two children at primary school – I asked her if she had told any of the other school mums she was struggling.

She replied: ‘How could I? My children go to school in Twickenham!’”

The story is the same in Hammersmith & Fulham for Daphine Aikens.

“So many people arrive feeling so angry, upset, embarrassed, ashamed. You can see they’re really tense, or sometimes they start crying immediately – nobody really wants to be in a food bank,” she said.

“Having somebody leave feeling better, thinking ‘that was okay, it was nothing like I was expecting it to be, this is a safe place I can come and talk to them about my life’.”

At a holiday club run by Daphine, one parent said to her: “Bringing my children here helps me forget for a moment that we’re poor.”

[Preparations for a Hammersmith & Fulham Food Bank holiday club, held outside school terms when children cannot rely on free school meals – Photo: @hffoodbank]

No matter how well-paid, how comfortable, how high up the social ladder a person is, poverty can strike anyone at any time. All it takes is a significant-enough change in their material circumstances.

“It used to be about 42% of people came to us because of benefit changes or delays,” said Caroline. “But that also means three in five come to us for other reasons.

“There is a misconception that everyone who comes us are scrounging or on benefits and can’t be bothered to work – that is just not true. Rents have increased, wages haven’t and people struggle to find themselves with enough money.”

In Daphine’s experience, poverty strikes entirely indiscriminately.

She said: “We do see people who have been in incredible high-power, well-paid jobs, who for whatever reason have lost their jobs. It could be a family breakdown, a mental health breakdown, it could be just a loss of job. They are not able to work for whatever reason, and they just need a food bank.”

A common response from parents is to ensure their children are always put first, perhaps to hide them from the reality of the situation, but primarily because they cannot bear the thought of them feeling the impacts of poverty at such a young age. And it is always to the parents’ own personal cost.

Caroline tells of a couple who would share a can of soup at night, rather than cut into their children’s meals. “The children generally are the last ones to suffer,” she says.

“The parents will themselves not eat, so they can feed the kids.”

As Daphine Aikens points out however, it can often be a losing battle.

She said: “If a child is hungry, it’s going to make them much harder to concentrate at school. If they’re hungry they’re probably tired because they’re not sleeping.

“If they’re cold because there’s no heating, if they can’t wash because there’s no hot water, they might go to school and stand out from other kids. Anything that makes a child seem different from others is never going to be good.

“A child growing up in poverty, it doesn’t matter how loving and wonderful their parents are – and loving and wonderful parents are going to do their best to prevent their child from experiencing the impact of poverty, they will protect them as much as possible – they’re not going to be able to do it.

“The kids are going to detect tension in the home, they’re not going to have the things that other kids have.”

[Siobhain McDonagh MP (standing) speaks during her February 22 parliamentary debate on child poverty in London – Photo: Hansard]

During her introductory speech, Ms McDonagh recalled a child who explained that if they were to win the lottery, they would spend their winnings on cereal and porridge to keep warm.

“These are the dreams of a child in London in 21st-century Britain,” she said.

“In reality, the only lottery he has been involved in is the lottery of birth – he has lost that lottery and the consequences will be lifelong.”

Nowhere is poverty’s postcode lottery more evident than in Ms McDonagh’s own borough of Merton. A male born in Cricket Green will grow up just three miles from a male in Wimbledon Village, but his life expectancy will be 14 years shorter.

Ms McDonagh targeted housing, demanding that the government utilise ‘non-green’ green belt land around train stations and for the unlocking of public pension funds for redistribution into social housing provision.

For Daphine Aikens, the situation is desperate, and change cannot come quickly enough.

“The idea of things getting any worse than it is now is absolutely horrifying,” she said. “But I’m afraid it probably is the case – I think it’s going to get worse.

London is the second-richest city in the world. The capital is home to £2 trillion in private wealth, and has more multi-millionaires than any other urban centre. And yet, in 2018, this is the reality of those living just beyond their doorstep.

“Food banks were initially set up to provide an emergency supply of food, short-term interventions,” Daphine says.

“As time goes on we’re becoming a service people need each week to survive, and I don’t know what the solution is.”

Some names in this story have been changed at the contributor’s request.