Many women in the UK have been made to feel like it is a trend amongst doctors to prescribe birth control for about every problem that they are faced with, as a solution for all their health concerns.

Menstrual pain or hormonal issues reported to doctors are either brushed off as ‘normal’ or prescribed a hormone altering contraception whether it is user dependent pills, or LARCs (Long-Acting Reversible Contraception) as the only way to escape their cycle of pain.

However, do women in the UK really know what is in their birth control?

A survey conducted by the Family Planning Association (FPA) in the UK found that while most women are familiar with the basic idea of contraception and the methods available, many lack detailed knowledge about the specific ingredients or how different contraceptives work.

For example, while many women know birth control pills contain hormones, fewer know which hormones are involved (e.g. oestrogen or progestin).

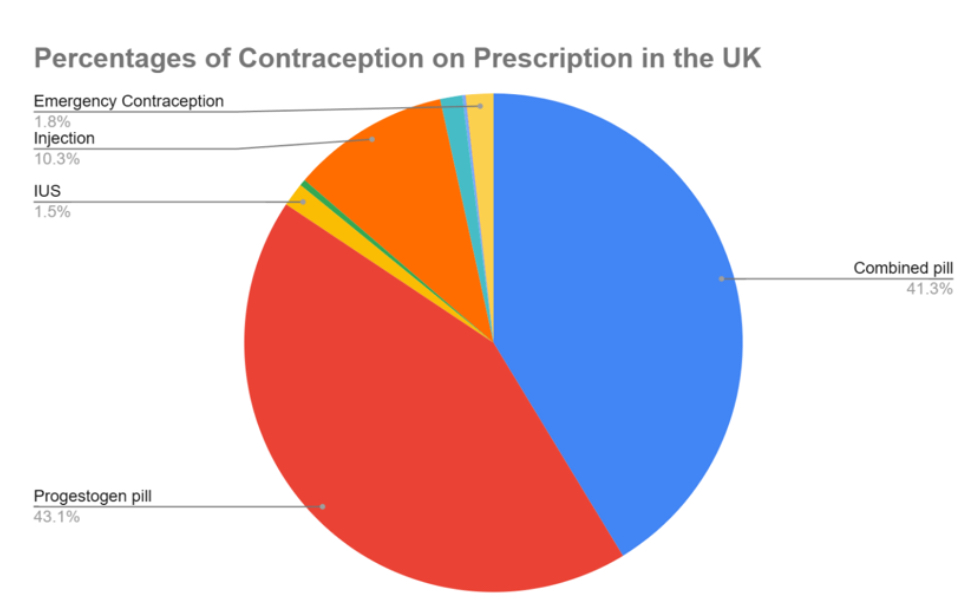

The most common types of birth control in the UK are the contraceptive pill (combined and progesterone only) followed by the contraceptive injection, implant, IUD, patch, ring, condoms and the morning after pill.

The other data on the chart stands for 0.44% IUDs/coil (green), 1.4% for the Patch (light blue), 0.2% for the Vaginal Ring and >0.01% for diaphragm and caps gathered from GPrX contraception data online.

Research suggests that while women are generally satisfied with their contraception choices, many do not receive detailed explanations from healthcare providers about the specific components of their birth control methods.

This may also contribute to gaps in their knowledge about ingredients.

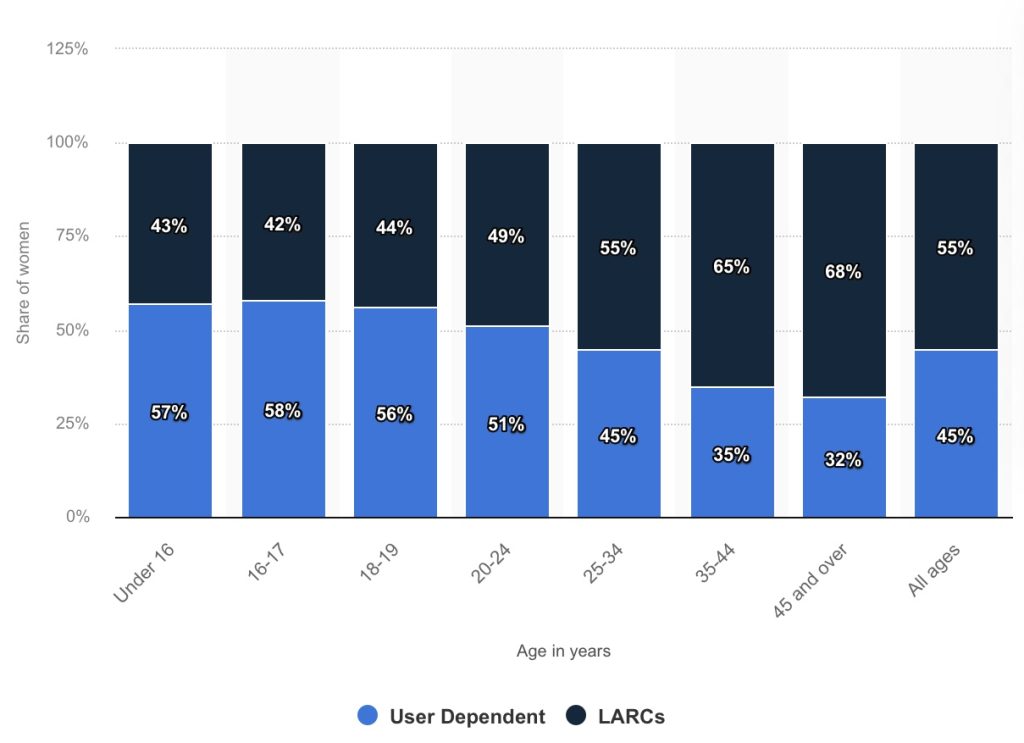

An increasing number of women are moving away from the pill and condoms, opting instead for LARCs, such as the implant or coil and younger women are driving this shift, according to NHS England data.

Dr. Matthew Chou said he frequently fits IUDs for women seeking hormone-free contraception, often due to mental health concerns.

However, he explained that there is no definitive data clearly linking hormonal contraception and mental health issues.

For many women in their 20s, hormonal contraception has been a part of life since they were teenagers.

Some feel they have never truly experienced adulthood without taking something that might influence their mood.

Sophie, 24, who started the pill at 17, began to question how it might be affecting her mental state.

“I just wanted to understand what it was doing to me and how I’d feel without it,” she said. She’s now exploring the option of using a diaphragm but mentioned that her GP practice didn’t seem familiar with it.

A diaphragm is a barrier method of contraception, it’s a soft, dome-shaped silicone device that fits inside the vagina and covers the cervix to stop sperm from reaching the egg.

It is recommended to be used along with a spermicide to be effective and needs to be left in place for at least six hours after sex, according to the NHS.

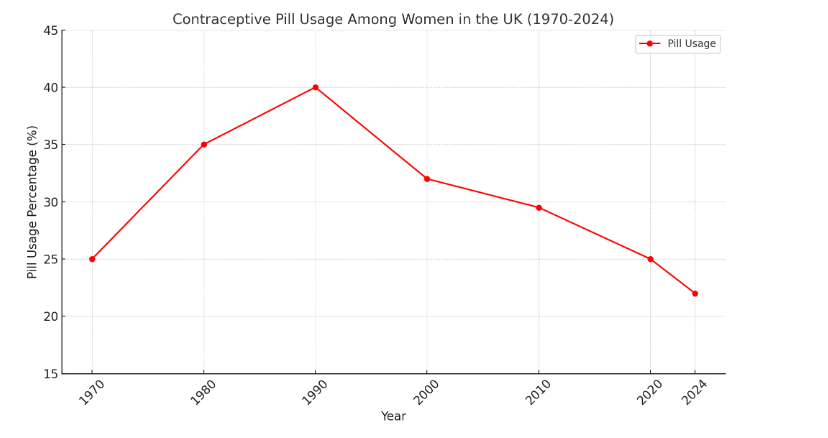

When it was first introduced nearly 60 years ago, the pill represented a major societal breakthrough, but now, a new generation of women is calling for a wider range of contraceptive options.

Zoe, 30, who has polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), began using the combined pill at age 16.

She said: “I tried a lot of combined pills, but they all made me emotionally unstable. Then I switched to the progesterone pill, but I had constant bleeding.

“The coil was recommended to me as a solution, but sadly, I bled the entire time I had that too.”

Oral contraceptives, such as the pill, remain the most widely used form of contraception, with 44% of women accessing contraception through sexual health services opting for it.

However, its use has declined over the past decade, with prescriptions through primary care services, including GPs, also decreasing.

In 2007, 21% of women in England who sought contraception through NHS sexual health clinics selected a type of LARC and by 2017, this figure had nearly doubled to 39%.

The National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (NATSAL) in the UK, which collects data on sexual health and contraception use, has explored how much women know about their contraceptive methods.

It found that although many women are aware of hormonal contraceptives and their general function, many do not fully understand the ingredients or potential side effects, especially in relation to long-term hormonal use (like the pill or IUD).

This is particularly concerning given the growing prevalence of LARCs among young women and girls, many of whom may be unaware of their potential long-term effects.

Although, it should be made clear that these figures may not represent the entire population, as they primarily reflect the women who have accessed Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH) services.

Additionally, the availability of over-the-counter progesterone-only pills since July 2021 may have influenced these statistics, potentially causing underreporting in SRH service data.

Part of the reason for women feeling ignored and misinformed by doctors could potentially be linked to medical misogyny.

Medical misogyny is when women feel a systemic or individual bias, discrimination, or dismissal of female health concerns, experiences, or needs towards them within medical practice.

It stems from historical, cultural, and structural inequalities that have often led to women being underrepresented, misunderstood, or undervalued in medical research, practice, and treatment.

As well as this, gynaecology wait times in the UK are a major cause for concern.

More than three quarters of a million women in the UK are waiting for hospital treatment for severe gynaecological problems.

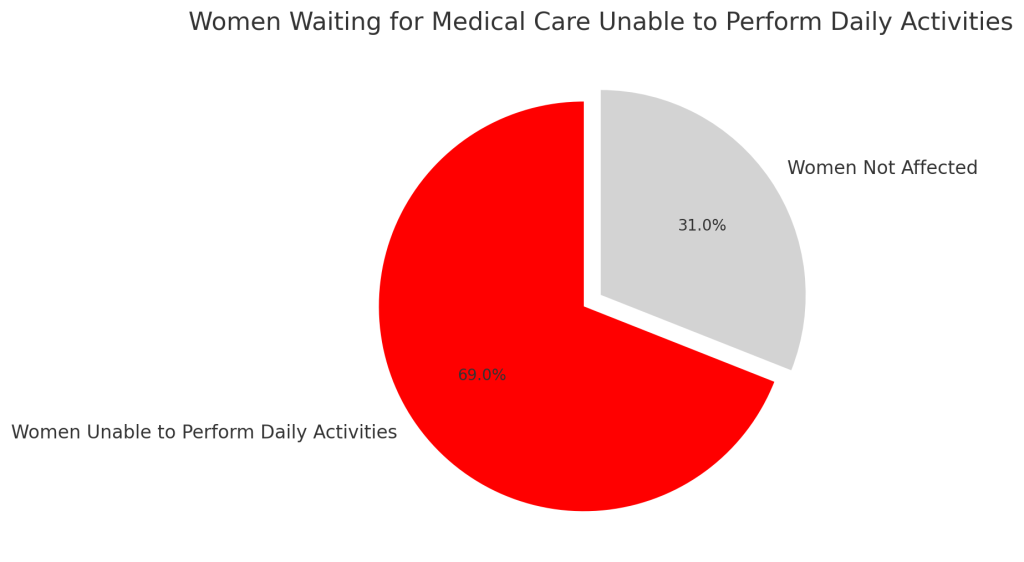

Emergency hospital admissions for women’s issues have increased by a third in three years as their symptoms worsen and more than two-thirds of those women waiting for medical care cannot do day to day activities, including work.

A Department of Health spokesperson said: “It is totally unacceptable that women with reproductive conditions are not getting the care they need and that their voices are not being heard.”

Another longstanding concern for women looking into going on contraception is a potentially heightened risk for certain types of cancer.

A study was conducted by Oxford University about the relation between hormonal contraceptives and the risk of breast cancer, which showed a 20-30% increase among users of the combined oral or progestogen-only contraceptive pill.

However, Gillian Reeves, a professor of statistical epidemiology and director of the cancer epidemiology unit at Oxford University stressed that for women in their 20s and 30s who regularly take birth control, the rates of breast cancer are very, very low.

Researchers from France have found that extended use of certain progestogen-based medications is associated with an increased risk of meningiomas, which are typically benign (non-cancerous) tumours that develop in the tissues surrounding the brain.

However, while the risk of meningioma was higher for women who took the medications for over one year, one leading expert said the finding should not worry previous or current users because the elevated risk remained “extremely small”.

There were many different types of progestogens used in the research and no association with meningioma was found for those commonly used in the UK.

Research in this area is ongoing, and NHS medical advice is that hormonal contraception can raise the risk of blood clots and breast cancer, and though this risk is very low, it does mean hormonal contraception is not suitable for everybody.

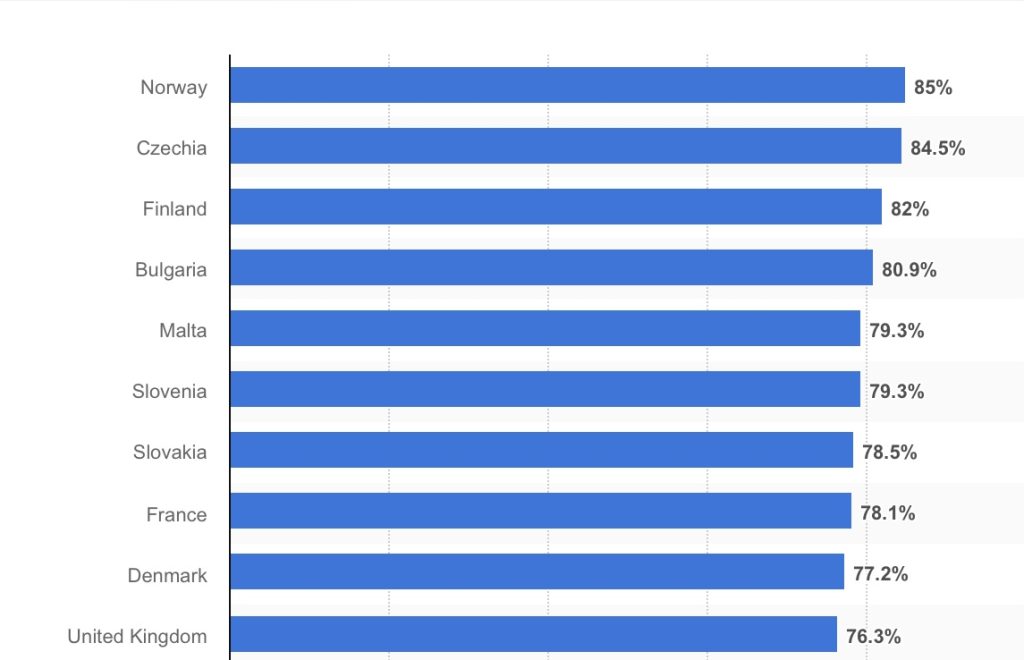

Contraceptive use in the United Kingdom is high compared to many other European countries. In 2022, the prevalence of contraceptive use in the United Kingdom was 76%.

See below this graph representing the share of women using any method of contraception in Europe: