As trust in the British media continues to fall, an increasing number of people in the UK admitted to actively turning away from the news whenever they can.

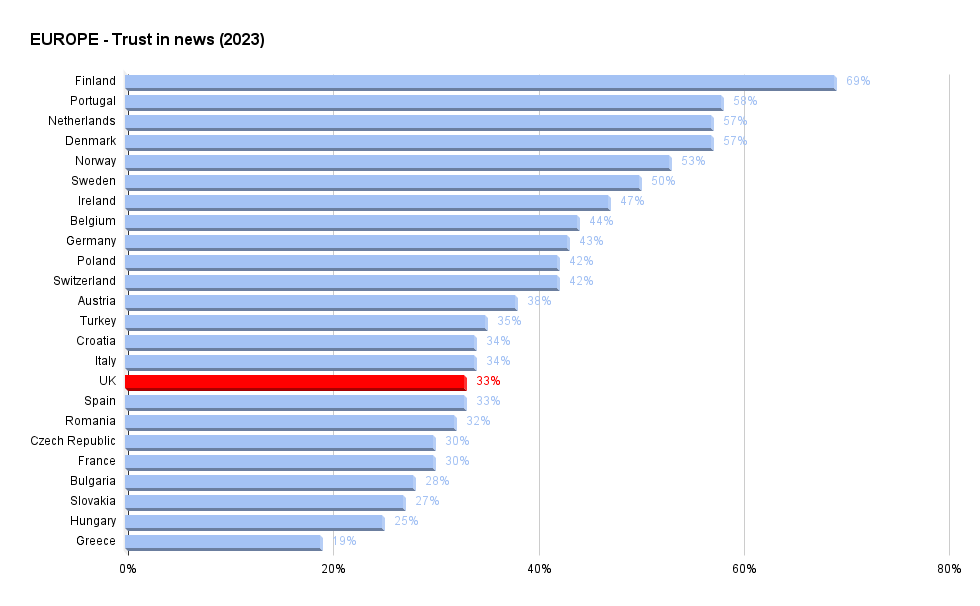

According to the Digital News Report 2023 by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ), only 33% of Brits surveyed claimed to trust the news, the lowest level among north European countries and the 12th lowest among the 46 target markets.

The annual report investigates news consumption worldwide and it is based on original survey data from six continents, collected through 93,000 interviews.

Among the 2,017 British participants, people aged 55+ showed the highest percentage of overall trust in news coverage (37%), while the lowest (27%) was registered among those aged 25-34, followed by individuals in their mid-30s and early 40s.

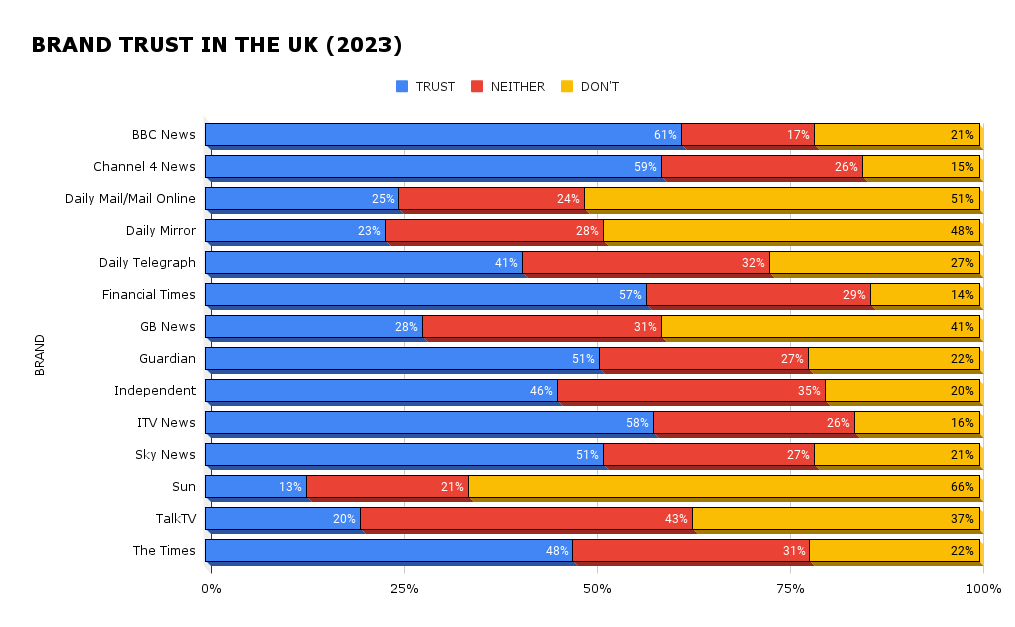

The most trusted news brand was the BBC (61%) – although its trust level has been falling since 2018 when it was at 75% instead – followed by Channel 4 News (59%) and ITV (58%).

Tabloids populated the bottom of the list (Fig. B): the least trusted was The Sun (13%), followed by The Daily Mirror (23%) and The Daily Mail (25%).

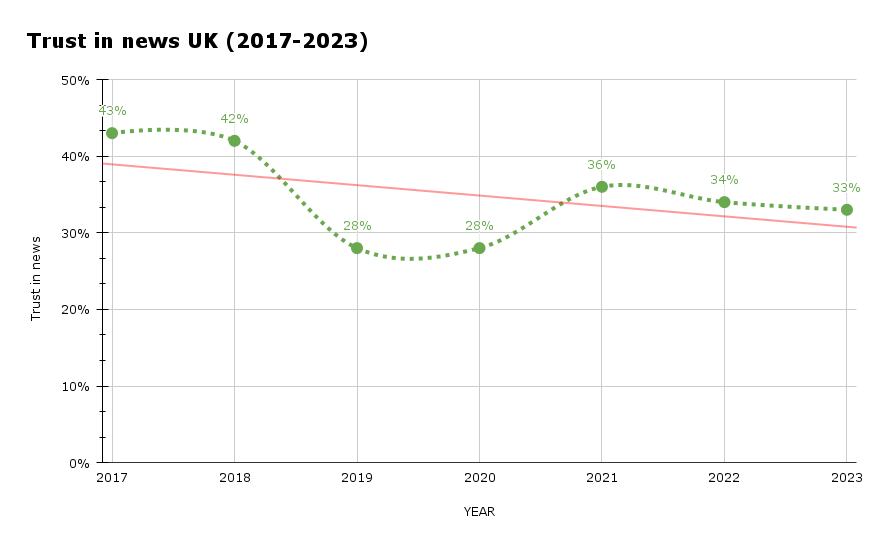

Data show that public trust in news has not yet recovered from the sharp decline in 2019 (28%), and despite a timid increase during the Covid-19 pandemic, the percentage of people in the UK who claimed to be sceptical is still high and represents a serious problem for the media industry.

Eeva-Maija Jokiniemi, a Finnish professional living in the UK, said: “Finland used to have quite a strong culture of unity. The media was not as polarised as in the UK, and the idea of the news actually trying to deliver objective truth has historically been strong in the country.

“Political aims can be clearly seen in the UK media, especially when it comes to choosing the point of view or topics to report – for example, how tabloids are leaving out commentary on government’s decisions but focus on antics of the Royal Family instead.”

Finnish news remains the most highly trusted (69%) among the 46 countries surveyed, with nationals over the age of 55 recording the highest percentage (75%).

According to the report, the country has maintained its trust levels after the pandemic bump, and events such as the NATO accession process and the war in Ukraine may have increased public trust in experts, institutions and, consequently, the media.

Jokiniemi explained: “Social cohesion in Finland has generally been high, so people find it easier to trust fellow Finns, and this idea still extends to news until some extend.

“Most Finns follow or are aware of the news from main national news channels – The Finnish National Broadcast YLE or Yleisradio, commercial news channel MTV3 News – and the biggest newspaper of Finland – the Helsingin Sanomat.

“These channels try to avoid the most polarising ways to report on issues, and the Finnish Association of Journalistic Ethics Julkisen Sanan Neuvosto has a strong position in regulating the news.

“False reporting and unethical journalistic behaviour are usually held responsible, which also helps maintaining the trustworthiness.”

Social cohesion, ethical reporting and a sense of institutional unity play a key role in the public’s perception of media trustworthiness.

As Rasmus Nielsen, co-author of the Digital News Report, pointed out, data show that in countries with lower degrees of political polarisation and a strong social contract between journalists and the public, people confidently expressed their trust in news.

He explained: “During the pandemic […] in a moment of crisis and uncertainty in lots of different parts of society we saw some increases in trust in journalism, and also in government, health authorities and scientists.

“That rallying around institutions has disappeared since the agenda has returned to become focused on divisive and contentious issues, often dominated by politicians that many people don’t really like, so that sort of Covid bump has disappeared.”

In their report on how misrepresentation and underrepresentation of disadvantaged communities undermine their trust in news, Reuters researchers found that UK participants believed news coverage often pitted social classes against each other intentionally.

Many argued that the persistent marginalisation of working class people, for instance, contributes to the perception of the media as “an extension of systems aligned to serve those in power”, and described it as “biased, sensationalistic or depressing, with distinctly personal and consequential stakes”.

In contrast, countries with high levels of trust in news seem to have in common low political interference, stable political environments and less social division.

The latest World Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders ranked the UK 26th (down from 24th last year), highlighting a “restrictive political climate” in which legislative proposals with worrying implications for journalism continued to move through Parliament.

Northern European countries once again top the list, with Norway being the country with the most robust press freedom, followed by Ireland, Denmark, Sweden and Finland.

The connection between trust deficit, press freedom and what researchers called news avoidance – the conscious decision to opt-out of news – is also undeniable.

Dr Leonardo Bevilacqua, lecturer in developmental psychopathology at the University College London (UCL) Institute of Education, explained: “News avoidance as a phenomenon lies within a general attitude of avoidance of a stimulus that is perceived as anxiety-provoking.

“It is plausible that this attitude developed particularly quickly during lockdown when we were more exposed to the news, having fewer opportunities for outside entertainment, and it has intensified in recent years due to the increasing ease of access to information and events such as the pandemic, and the wars in Ukraine and in the Middle East.”

RISJ’s report showed that although the percentage of Brits actively avoiding the news (41%) registered a 5% decrease in 2023 compared to the previous year, it remains one of the highest rates across markets.

The highest number of avoiders was registered among people aged between 35-44 (45%), followed by those aged 25-34 (44%).

Overall, more women (44%) than men (38%) said they sometimes or often try to avoid the news.

Young people in the 18-24 group registered the lowest level of news avoidance (37%), with YouTube and social media being their main source of information.

Researchers found that half of avoiders actively get away from all news or scroll past it on social media, while the rest of them take more specific actions to reduce their consumption, for example by turning off notifications or not checking their phones.

Nic Newman, lead author of the Reuters Digital News report, explained that a significant proportion of people chose to avoid “emotionally draining” news stories that made them feel depressed or anxious.

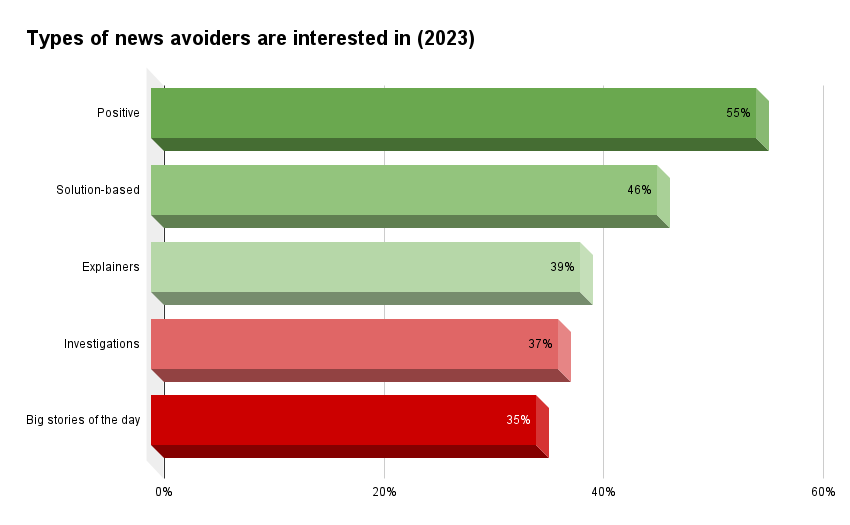

Indeed, almost four in ten avoiders admitted to having avoided news on the war in Ukraine, national politics and issues concerning social justice, in favour of more positive and solution-based news.

Newman said: “What was interesting is that news that avoiders liked the least was the constantly updating big stories of the day, and for people that never avoid the news that’s the news they like the most.

“News sites are quite often set up to super-serve people who are really interested in news but that also seems to be turning other people away.”

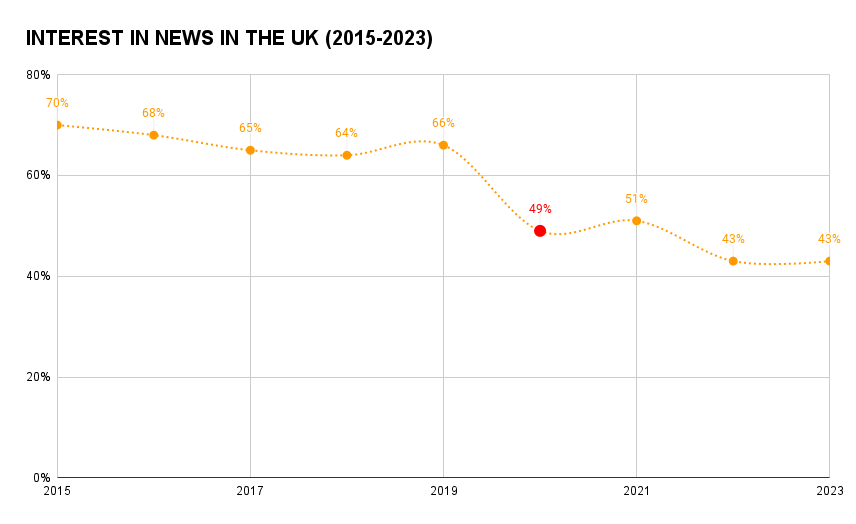

Interest in news continues to decline in the UK, going from 70% in 2015 to 43% this year.

Unlike the upsurge in news consumption during the pandemic, major events such as the war in Ukraine or the cost-of-living crisis did not get the same public attention.

On the other hand, the percentage of Brits who said they were totally disconnected from the news has increased again this year and is now at 9%.

According to researchers, to regain public trust in their coverage, news organisations must promote relationship-building initiatives that appeal to those who have given up on the idea of trustworthy journalism.

These may include solutions-focused and constructive coverage, transparency, journalistic independence, diversity in newsrooms, and engagement initiatives.

“It’s been a tough year and the report reflects those challenges,” Newman said.

“There are many parts of the world where journalism is doing an amazing job where is highly trusted, where there is a group of publishers who are delivering high quality journalism and adapting to this new world which can be summarised being about building lasting long-term relationships through podcasts, newsletters, new formats.”

Featured image credit: Rich Smith on Unsplash