Underground, walking between towering walls of moss green compartments, I am handed a fungus around the size of a newborn baby, and only slightly lighter.

Lee Davies, collections manager at Kew’s Fungarium, knocks on its side, producing the hollow sound of wood.

He tells me: “That’s a bracket fungus. It eats trees – but in a good way. The part you’re holding is the fruiting body of the fungus, which makes it essentially the fungi’s genitalia. All of the specimens here are the parts of fungi responsible for reproduction – making all of this 1.3 million boxes of genitals.”

Lee, who talks quickly and hates the taste of mushrooms, is showing me around the largest fungi collection in the world and a leading international depot for its scientific research. He points to a few packages lying on his desk, which is fantastically decorated with mushroom paraphernalia, and talks me through their various destinations: Czech Republic, Italy, Canberra…

Within the natural sciences, Mycology – the study of fungi and mushrooms- is sort of the new, weird, kid on the block. At least to the western world, it would appear to occupy an alien territory, where the residents look different, think different, manufacture psychedelics and sometimes kill their unwitting visitors.

Despite efforts from age-old institutions like Kew’s Fungarium, founded in 1879, this has long been the dominant cultural perception of fungi and mushrooms; a fringe movement only to be explored by psychonauts and green fingers. But that’s a perception that’s begun to change – and rapidly.

Lee explains: “There was a defining point about five years ago when it started appearing more in popular culture. There were books, that video game, a film – it’s become much more part of the consciousness now, which is certainly a good thing. We have to ride on the back of that interest, because in fungi, you have to use attention.”

Popular documentaries such as Fantastic Fungi, books like Entangled Life, and pieces of fiction such as The Last of Us have contributed to the ignition of a sudden cultural attention to our planetary recyclers. A few years ago, scarcely anyone had heard of the term cordycep, the species of parasitic fungi that possess the brains of insects – fast forward to a couple months ago, and they’re being discussed in Good Housekeeping for their health benefits.

Though Lee explains to me that various types of fungi, such as Lion’s Mane, have been proven to have some striking effects on the human brain and body, the current, unregulated sale of mushrooms for medicinal purposes was something he was quick to caution against.

“There’s definitely some snake-oil stuff going around. You’ll hear about fungi that are good for a very broad mix of things, but at no point will they identify the actual compound doing these things, how much is needed for it to be effective, and how much there is in what they’re selling you.”

Friend or foe?

Whilst mycologists such as those at Kew continue to uncover the mysteries of fungi, the optics on the field are tentative, with society unsure whether its immeasurably significant place in the natural world is something we should be afraid of or inspired by. Fungi is after all, the source of penicillin, as well as 19 separate pathogens currently believed by the World Health Organisation (WHO) to be a threat to humanity.

It is one of those pathogens, Candida auris, that has brought a recent swell of media attention toward the field. Discovered in 2009 inside a Tokyo woman’s ear, the pathogen has now spread to more than half of the states in America. Lee explained that the truth behind this pathogen’s rapid spreading is actually far more troubling than first thought.

“Typically, fungi don’t tend to like us as we’re relatively hot organisms and they can’t tolerate the heat, but climate change, and global temperature increases are in a way, accelerating natural selection. The more heat tolerant fungi are surviving over others and becoming more dominant, and that means we’re much more accessible to them.

“Fungal diseases are really difficult things to treat in humans, and there’s hardly any anti-fungal compounds out there in the world for these things. So, it’s kind of a ticking time bomb.”

Lee walks me through to what he calls the ‘dirty lab’, it’s the front line for taxonomy at the fungarium, a white-coated space filled with scientists working on specimens as they arrive – dirt, debris and all – from foragers eager to find out if they’ve discovered a new species. He stands me behind some PhD students tweezing a petri dish.

“There are definitely big gaps in our understanding, there’s sort of black holes across the globe in terms of our knowledge of fungal biodiversity. Even across Europe, or the UK, it’s very easy to find new species here.

“If we’re being conservative, there could be two to three million species out there in the world that we don’t know about yet. It could even be up to six million, which is slightly terrifying.”

Terrifying, but potentially awesome in scale too. Recent discoveries in fungi have yielded radical results in terms of its role in facilitating a greener, more sustainable future. Take, for example, its ability to produce alternatives to not just meat, but leather, plastic and even medicines. Equally, its potential to sequester carbon and its role in climate restoration is starting to be treated more and more seriously.

In an article co-written for Time magazine in February 2023, mycologists Giuliana Furci, foundress of the Fungi Foundation, and Merlin Sheldrake, author of Entangled Life, called for fungi to be added to conservation frameworks as an inseparable, third ‘F’ to the traditionally considered ‘Flora’ (plants) and ‘Fauna’ (animals.)

Toward the end of their piece, the pair wrote: “Accounts of the living world that do not include fungi are accounts of a world that doesn’t exist.”

Finding your fungi

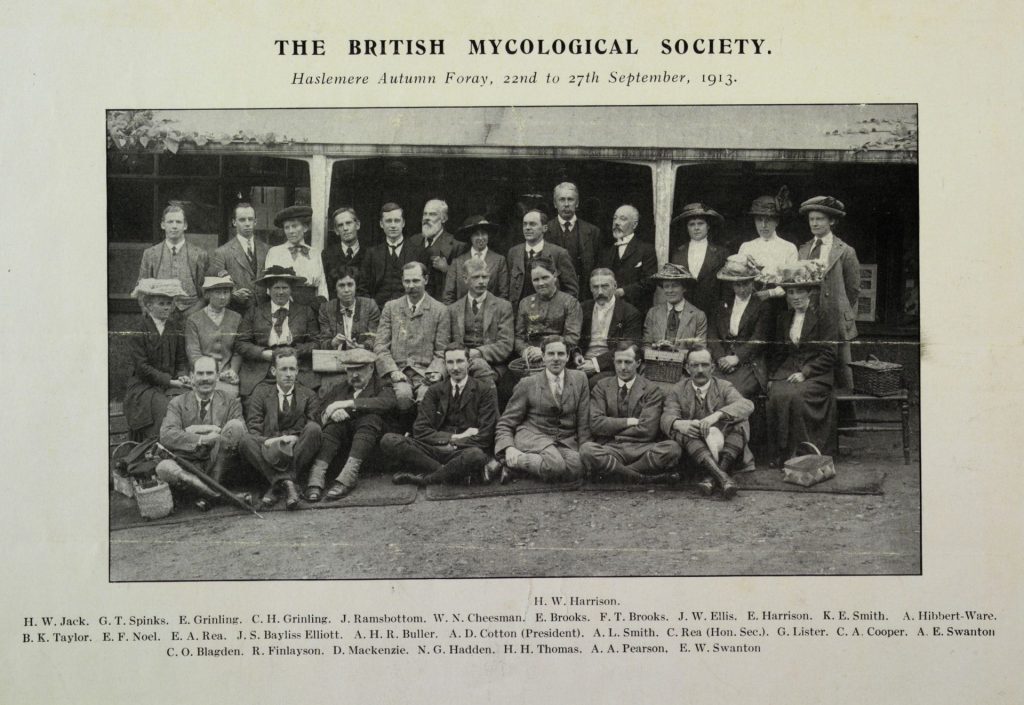

A few weeks ahead of my visit to the fungarium, I spoke with author and educator, Andy Overall. Better known as ‘Fungi to be with’ to those who attend his workshops and forays, Andy is a member of the British Mycological Society, a group established in 1896 to promote the study of fungi. He told me about a recent boom in the society’s membership, and I wanted to ask him what he thought was behind it.

Andy said: “I think some of the old, negative perceptions of fungi are now being seen as positive associations. We understand the importance of their role in decaying organic matter for an ecosystem, or that small amounts of Psilocybin (the active compound in magic mushrooms) can be used to treat mental health issues.”

Providing fungi foraging tours specifically to Londoners, Andy believes that getting hands-on with nature is a fundamental method for building a connection with it. He himself became interested in mushrooms back in the 80s, after a childhood growing up in the Essex countryside. He tells me: “Some of the biggest hazards that someone new to mycology might face, are actually from the public’s perception of what you are doing. Some members of the public can be very precious about ‘their green space.’”

Early, tangible experiences in nature, which Andy now helps to facilitate himself, have been the traditional entry point for those currently involved in the field. But what can those who are bound to an ‘urban’ environment do to further a newly developing interest in mycology?

The London Fungus Network, founded in 2020, answers that question by connecting forays like Andy’s with lecturers, workshops, magazines, and other fungi related experiences taking place around the capital.

On a rainy day a week or so after my visit to the fungarium, I spoke with the group’s founder and director, Michael Green.

“Our mission is to connect people with the urban fungal kingdom and introduce people to these amazing organisms that are all around us – even on our doorsteps.

“People ask me ‘where can I find mushrooms in London’, and I always say it’s not a matter of where, but about how. The way to find mushrooms is just to slow down, be a bit more mindful and suddenly these amazing organisms will start appearing all around you – there’s a patch even at my local bus stop.”

Mike founded the London Fungus Network after a visit to the Telluride Mushroom Festival in Colorado. He told me he had been overwhelmed by the sense of community he had found at this eccentric gathering of people, and he wanted to try and replicate it in London.

“At first, the people who came to our groups already had some experience with fungi, from foraging or research, but more recently the people coming have been complete newbies.

“So now we’ve been helping people to identify some of the more common species, which allows them to get to know their fungal neighbours a bit better. We take them out in autumn, in winter, and it’s a thrill to watch these people have their first experiences with a wild mushroom.”

Mike mentions that the first official speaker at the London Fungus Network was in fact, Giuliana Furci, the previously cited foundress of the Fungi Foundation and renowned National Geographic explorer. He’d met her at the Telluride festival, the very place that had first inspired Mike’s network and the place he will once again be flying out to this August – this time however, he tells me it will be as an invited speaker.

He lets me know earnestly: “It’s really, really exciting. Mushroom goals, you know?”

My visit to the fungarium finished with a handshake from Lee and the careful process of me being buzzed out through a sequence of heavily secured doors. I said goodbye to the PR representative for Kew Gardens who walked me to the gate at its exit. Taking a glance back, I saw the bursting flora of the gardens, its rich colours lit by the early days of spring.

It is the vision of the natural world that many would acknowledge as its best champion. But after an afternoon spent amidst the peculiar specimens of a carefully temperature-controlled bunker, I thought of Lee telling me that 95% of plants can only survive because of their fungal partner, and I couldn’t help but feel that these sightly gardens were only half of the story – one that most of us have barely begun to read.